Major Clarke’s A-7D made ‘a very low pass’ on the guns to protect the Jolly and took a hit ‘by something that felt like a 57mm.’ He lost all his systems and pulled up into the clouds ‘with what I hoped was wings level. About that time a SAM radar picked me up, and things didn’t look too good….’

The U.S. Navy’s A-7 was the basis for the single-seat, tactical close air support aircraft known as the A-7D. The first A-7D made its first flight in April 1968, and production model deliveries started in December of that same year. LTV had given the American Air Force 459 A-7Ds by the time production on the model ceased in 1976.

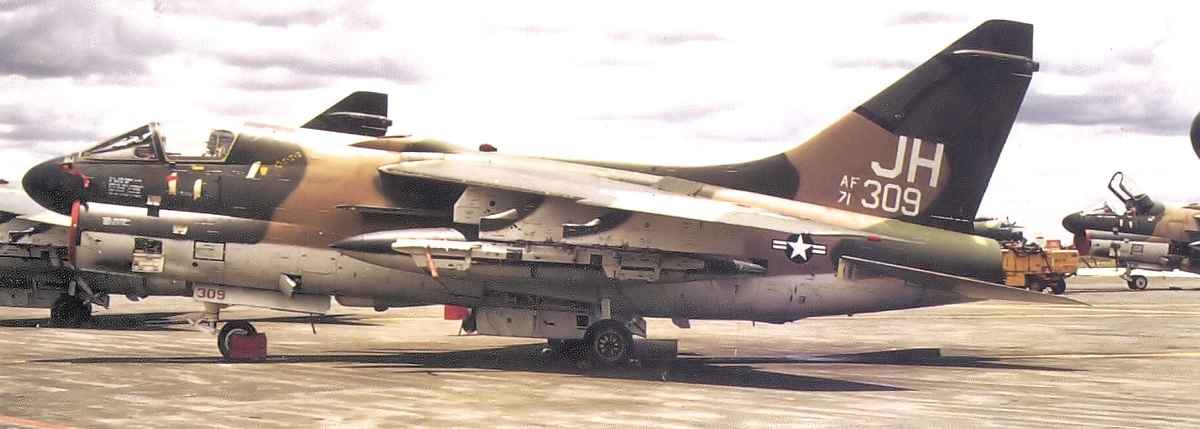

During the latter months of the Vietnam War, the A-7D flew with the 354th Tactical Fighter Wing (TFW) at Korat Royal Thai Air Force Base, Thailand, showcasing its exceptional ground attack capability.

The A-7 was built to provide close support to combat units in contact, which is the task that the 354th TFW anticipated carrying out when they entered the battle in late 1972. But at that point, the majority of American combat forces had been evacuated, so they were sent to two completely distinct tasks. Interdiction was hardly a surprise in the first place. The A-7s’ surprising assignment to take over the Search and Rescue (SAR) “Sandy” Role from the veteran and esteemed A-1 was met with skepticism in the second instance. The SLUF (Short, Little, Ugly, Fucker), as the A-7 was known by her aircrews, dispelled all skepticism three weeks after receiving her duty.

The following incident was first published in Air Force Magazine in August 1973 and then in Lou Drendel’s book A-7 Corsair II in action. John L. Frisbee, their Executive Editor, wrote it.

“On Nov. 16, 1972, an F-105 Wild Weasel had been hit by a SAM in the vicinity of Thanh Hoa, on the coast, some ninety miles south of Hanoi. The Weasel crew bailed out at about 11:00 PM, landing at the base of the first ridge line west of the city. The following day, three of the 354th Sandys went up in very bad weather and got the survivor located, part way up the ridge line, but separated from each other.

A SAR force of about seventy-five aircraft was put together late that day and during the night by the Joint Rescue Coordination Center at Tan Son Nhut Air Base, near Saigon. It included F-105 Wild Weasels to suppress the SAMs around Than Hoa, F-4 ‘Wolf’ FACs and F-4 MiGCAP aircraft, tankers, an HC-130 Kingbird (the mission coordinator), H-53 Jolly Green rescue Helicopters, A-7D’s with smoke for screening purposes, and three 354th TFW Sandy’s. Pickup was set for first light the following day, with takeoff for the Sandys at 0430.

Major Colin A. “Arnie” Clarke, who was operations officer of the 354th’s SAR organization, led the Sandys. He has been awarded the Air Force Cross for his part in the show.

The Sandys rendezvoused with the Jolly Greens above a solid overcast along the Laos-North Vietnam border. While the Jollys held in orbit, Major Clarke and his wingmen worked east from the Plaine des Jarres in Laos, looking for a break in the overcast through which a chopper could let down. Approach from the Gulf of Tonkin seemed out of the question. The Thanh Hoa area was heavily defended by anti-aircraft guns and SAMs, while just north of the town was a MiG field.

Major Clarke told his wingmen to hold while he let down several times into narrow valleys, trusting the accuracy of his Projected Map Display and radar altimeter. Each time he broke out under very low ceilings, the valley proved too narrow to turn in, and ahead the clouds closed down over rises in the ground.

Giving up on the valleys, Clarke climbed up on top, flew east, and let down over the Gulf to see if there was any way to work a Jolly through the enemy defenses along the coast. There wasn’t. He did get the survivors pinpointed and marked on his Projected Map Display so both men on the ground could be found immediately on return.

Clarke now went back over the Gulf, picked up his wingmen and the smoke-carrying A-7s, and took them in to see where the survivors were. The A-7s took several. 51 caliber hits. But whether the pick-up area had improved somewhat – 2,500-foot ceiling with lower broken clouds, rain, and three miles visibility. It was still too low for the supporting F-4s to use their delay-fuzed CBU antipersonnel bomblets against enemy gun positions. To the west, the only approach route for the choppers was still down in the valleys.

Everything pointed to an aborted mission. But Major Clark ‘knew that the weather wouldn’t be any better for days. The survivors couldn’t last that long.’ Having been shot down himself on an earlier tour as an F-100 ‘Misty FAC’, he knew that it was now or never.

going back west again, Major Clarke let down on instruments in a valley-wide enough to turn in. While he orbited just above the ground, one of the Jollys did a DF letdown on him, but ran low on fuel, climbed back through the clouds, and headed for home.

The mission was now six hours old.

Two more Jollys came up from Nakon Phanom and held while Clarke went out to a tanker for rest and fuel. At that point, he set a pickup time for the SAR force. Going back west, he once more let down on instruments in a valley ‘wide enough to hold a two-G turn’, and a chopper DFed down on his position – about forty-five miles west of the survivors.

Flying ahead and doing 360-degree turns to stay with the chopper, Clarke led it to near the pickup area, where he told the Jolly to hold while he went in to get the survivors alerted and suppress fire from enemy guns.

Clarke now discovered a .51 caliber gun position on the ridge, just above one survivor, who was hiding in tall brush. ‘A guy could have thrown a hand grenade from the gun pits onto the survivor.’ He and his wingmen kept the fire on the guns while the A-7 smoke birds laid down a screen.

By this time, there was a lot of lead flying around and a lot of chatter on the radio. The Jolly Green pilot decided to come in, unaware of the gun position close to one survivor. Miraculously, he made both pickups, then headed west, directly past the .51 gun pits.

Clarke made ‘a very low pass’ on the guns to protect the Jolly and took a hit by something that felt like a 57mm.’ He lost all his systems and pulled up into the clouds with what I hoped was wings level. About that time a SAM radar picked me up, and things didn’t look too good.’ The SAM apparently didn’t fire.

Clarke broke out on top, joined up with a couple of A-7s, and made an IFR landing at Da Nang, flying the wing of one A-7. Mission time: about nine hours.

The ’57mm hit’ turned out to have been a .51 caliber tracer that exploded one of his empty wing tanks, blowing in the side of the fuselage and bowing the underside of the wing.”

The Air National Guard (ANG) began receiving A-7D aircraft from the USAF in 1973, and by 1987, ANG units in 10 states and Puerto Rico were flying them. A-7D aircraft took part in Panama’s Operation Just Cause in 1989. In the early 1990s, the final A-7D aircraft were retired.

Photo by U.S. Air Force

Additional source: U.S. Air Force