The al-Hussein ballistic missile

Always at the forefront of Arab states when it came to the development of its armed forces and armament industry, during the 1970s Iraq embarked on an ambitious program of becoming self-sufficient in production of almost all equipment and ammunition necessary for its armed forces. Indeed, during the following decade, many of the related projects became a necessity because of the lengthy and costly war with Iran.

The most ambitious – and probably the best-known – such projects were related to the production of ballistic missiles: the efforts resulted in the construction of a factory for production of rocket propellant at Hillah and another for the assembly of ballistic missiles at Fallujah.

A direct result emerged in early 1988, when Iraq deployed the al-Hussein ballistic missile (an extended-range variant of the Soviet-made R-17E ‘Scud‘) to strike Tehran in Iran in the course of the so-called ‘War of the Cities.’

Project Babylon

As told by Ali Altobchi with Tom Cooper & Adrien Fontanellaz in their book Al-Hussein Iraqi Indigenous Conventional Arms Projects, 1980-2003, however, al-Hussein was far from being the only such project.

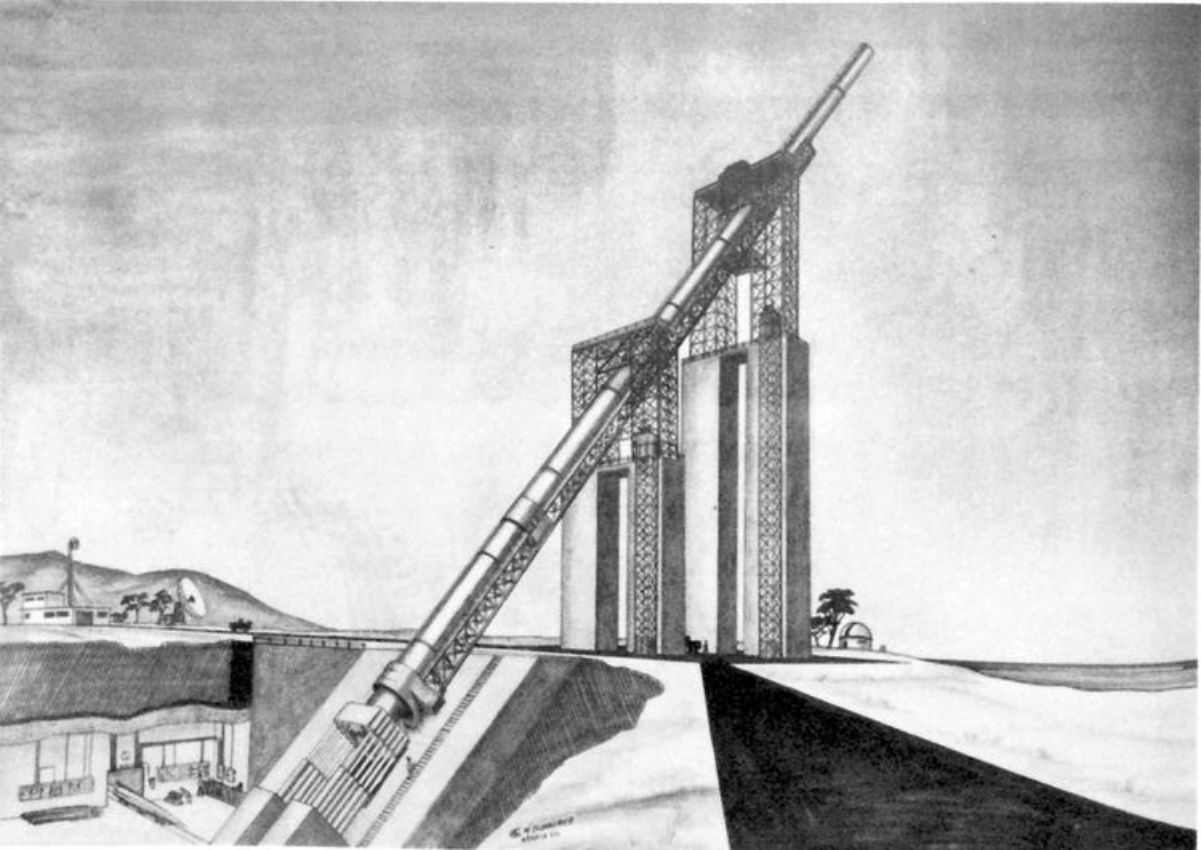

Indeed, within Project Babylon, the Iraqis cooperated with prominent Canadian artillery expert Gerald Bull to develop the so-called ‘super gun’: a 1,000mm artillery piece expected to be capable of reaching a range of 750km.

Intending to put a payload of 2,000kg into orbit – the minimum for a contemporary commercial satellite – while understanding that he still had to conduct much research and development for this to work, Bull and the staff at the Space Research Corporation (SRC) developed designs for two guns.

Babylon the main gun, was to have a smoothbore barrel of 1,000mm calibre, consisting of 26 sections bolted together to a staggering length of 156 metres, weighing about 1,665 tons. Other major pieces of its equipment included four recoil cylinders weighing 60 tons each), two buffer cylinders (weighing 7 tons each), and a 182-ton breech. Around the breech – made of steel with a tensile strength of more than 1,250 Mega Pascals – the barrel was to be 30cm thick to withstand a maximum operating pressure of 70,000psi. The overall weight of the gun was thus to grow to around 2,100 tons.

Baby Babylon

Baby Babylon was to serve as a prototype and was thus much smaller. It had a 46-metre long barrel with a 350mm bore weighed about 113 tons, and was to be of self-recoiling construction and thus mounted on rails.

Both guns were to be mounted horizontally, and – due to their sheer size and weight – could neither be moved, nor aimed. More was not necessary, however, because their purpose was of purely civilian nature: indeed, they made no sense as weapons. The detonation upon firing of Babylon was certain to create a fireball of about 90 metres diameter, and the power sufficient to be registered by seismographs even in the US: Bull was certain that every military force in the world would know its exact coordinates within minutes of the gun being fired.

Moreover, made of sections, the barrel would have been easy to knock out of alignment even by warheads that would miss by 1,000 metres. The only reason he preferred to keep the project secret was the fear that the US, Israel, and Great Britain would do everything in their powers to stop its development because they did not want Iraq to have reconnaissance satellites.

Project Babylon: Assembling a giant puzzle

The construction of two guns of such huge size was by no means easy: to a certain degree, it was reminiscent of assembling a giant puzzle, because it required the involvement of several highly specialized companies around the world. For example, the 52 barrel-sections were ordered from the British company Sheffield Forgemasters, its subsidiaries Forgemasters Engineering and River Don Castings, and the Walter Somers Company, in July 1988. All the parts were paid for by the Iraqis with an irrevocable letter of credit as soon as ready, and then shipped to Iraq.

Baby Babylon was originally assembled horizontal in a position at Jebel Sinjar (Mount Shingal). Following several initial experiments, by April 1989 it was relocated to Jebel Hamryn, near the village of Bir Ugla and thus in proximity of the Saad-16 complex, north-west of Mosul.

Projectiles intended to put a satellite into orbit

Once there, the gun was regularly fired over the following month, using propellant derived from a solid nitroglycerine base and made by PRB in Brussels (which shipped it to Iraq via Jordan under the guise of ordinary artillery propellent): it managed to fire test slugs at speeds of about 3,000 metres per second.

That said, by this time Bull was lagging with the development of the actual projectiles he intended to use to put a satellite into orbit: he did design a larger version of the Martlet IV, expected to reach a height of 27,000 metres, where the first stage rocket would ignite, and take the projectile to 48,000 metres, where the second stage would kick in. The third and final stage was to activate at an altitude of 80,000 metres, and take the satellite to about 105,000 metres, by when it would move at a speed high enough to eventually reach orbit at an altitude between 1,700 and 2,000 kilometres.

However, contrary to his usual fast work, this part of the project never reached the stage of actually being constructed. The reason was that Bull had meanwhile become involved in several other projects in Iraq, none of which was peaceful in its nature.

Al-Hussein Iraqi Indigenous Conventional Arms Projects, 1980-2003 is published by Helion & Company and is available to order here.

Photo by UNSCOM and Unknown