“The termination of the SR-71 Blackbird was a grave mistake and could place our nation at a serious disadvantage in the event of a future crisis,” Senator John Glenn

The Lockheed A-12 and YF-12A aircraft were used to create the long-range, cutting-edge strategic reconnaissance aircraft known as the SR-71, also known as the Blackbird. The first SR-71 to enter service was delivered to the 4200th (later 9th) Strategic Reconnaissance Wing at Beale Air Force Base, California, in January 1966. The SR-71’s first flight took place on December 22, 1964.

No SR-71 has ever been lost or damaged as a result of hostile action because of its remarkable speed, which allowed it to acquire intelligence while slicing through hostile skies in a matter of seconds. It could survey 100,000 square miles of the Earth’s surface per hour from an altitude of 80,000 feet.

The U.S. Air Force (USAF) retired its fleet of SR-71s on January 26, 1990, despite the aircraft’s remarkable flight characteristics, due to a decreasing defense budget, high operating costs, and the availability of advanced spy satellites.

“General Larry Welch, the Air Force chief of staff, staged a one-man campaign on Capitol Hill to kill the program entirely,” Ben Rich wrote in his book Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My Years of Lockheed. “General Welch thought sophisticated spy satellites made the SR-71 a disposable luxury. Welch had headed the Strategic Air Command and was partial to its priorities. He wanted to use SR-71 refurbishment funding for the development of the B-2 bomber. He was quoted by columnist Rowland Evans as saying, ‘The Blackbird can’t fire a gun and doesn’t carry a bomb, and I don’t want it.’ Then the general went on the Hill and claimed to certain powerful committee chairmen that he could operate a wing of fifteen to twenty [F-15E] fighter-bombers for what it cost him to fly a single SR-71. That claim was bogus. So it was claimed by SAC generals that the SR-71 cost $400 million annually to run. The actual cost was about $260 million.”

The SR-71 was retired as a result of testimony before Congress from both Welch and SAC commander General John Chain.

As Rich so aptly reflected, “A general would always prefer commanding a large fleet of conventional fighters or bombers that provides high visibility and glory. By contrast, buying into Blackbird would mean deep secrecy, small numbers, and no limelight.”

With the exception of training flights, Blackbird operations were officially discontinued in November 1989 after being cut from the Defense Department’s FY1990 budget.

One Blackbird is famous for breaking several speed records during its “retirement flight” on March 6, 1990. The Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum (NASM) Udvar-Hazy Center at Dulles Airport received the SR-71 with the tail number 64-17972 after it was flown from California. In the process, it achieved a coast-to-coast speed record for the National Aeronautic Association of 2,086 miles in one hour and seven minutes, or an average speed of 2,124.5 mph. With an average speed of 2,176.08 mph, it completed the 311-mile St. Louis-to-Cincinnati leg in under nine minutes.

Within a few months of this widely publicized flight, Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi army had occupied Kuwait, and the United States was taking part in the Desert Shield buildup, which culminated in Operation Desert Storm in January and February 1991. This information is provided by Bill Yenne in his book Area 51 Black Jets. Many military commanders, including General Norman Schwarzkopf, lamented the lack of quick reconnaissance that the SR-71 might have provided during that combat.

The Middle East and North Korea are among the global spots, and growing worries about these scenarios prompted Congress to reevaluate the SR-71’s activation. Admiral Richard Macke, the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s director of joint staff, informed Congress in 1993 that “from the operator’s perspective, what I need is something that will not give me just a spot in time but will give me a track of what is happening. When we are trying to find out if the Serbs are taking arms, moving tanks, or artillery into Bosnia, we can get a picture of them stacked up on the Serbian side of the bridge. We do not know whether they then went on to move across that bridge. We need the [reconnaissance information] that a tactical, an SR-71, a U-2, or an unmanned vehicle of some sort will give us, in addition to, not in replacement of, the ability of the satellites to go around and check not only that spot but a lot of other spots around the world for us. It is the integration of strategic and tactical.”

Congress approved a resumption of money in its FY1994 appropriations to allow for the reactivation of a portion of the SR-71 fleet. Many of the twenty SR-71s that were still flying at the time were being prepared for museum exhibits, but at least a dozen were being stored at Palmdale or participating in NASA research missions.

Because the USAF moved too slowly toward reactivating the SR-71, President Bill Clinton vetoed the money in October 1997. Only two Blackbirds remained at NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center at Edwards AFB when the US Air Force ordered the aircraft permanently grounded in 1998.

The Linear Aerospike SR-71 Experiment (LASRE) series, carried out in 1997 and 1998, was one of the final NASA missions for the SR-71. The goal was to investigate how lifting bodies and aerospike engines performed in terms of aerodynamics. This was done using the Lockheed Martin Skunk Works X-33, a prototype for the VentureStar single-stage-to-orbit reusable spaceplane. After NASA ended the latter program in 2001, Lockheed Martin continued to work on it.

The last words that Americans heard when discussing the Blackbird’s fate are those that Senator John Glenn said on the Senate floor the day following the 1990 “retirement flight.”

Said the former astronaut, “The termination of the SR-71 was a grave mistake and could place our nation at a serious disadvantage in the event of a future crisis. Yesterday’s historic transcontinental flight was a sad memorial to our shortsighted policy in strategic aerial reconnaissance.”

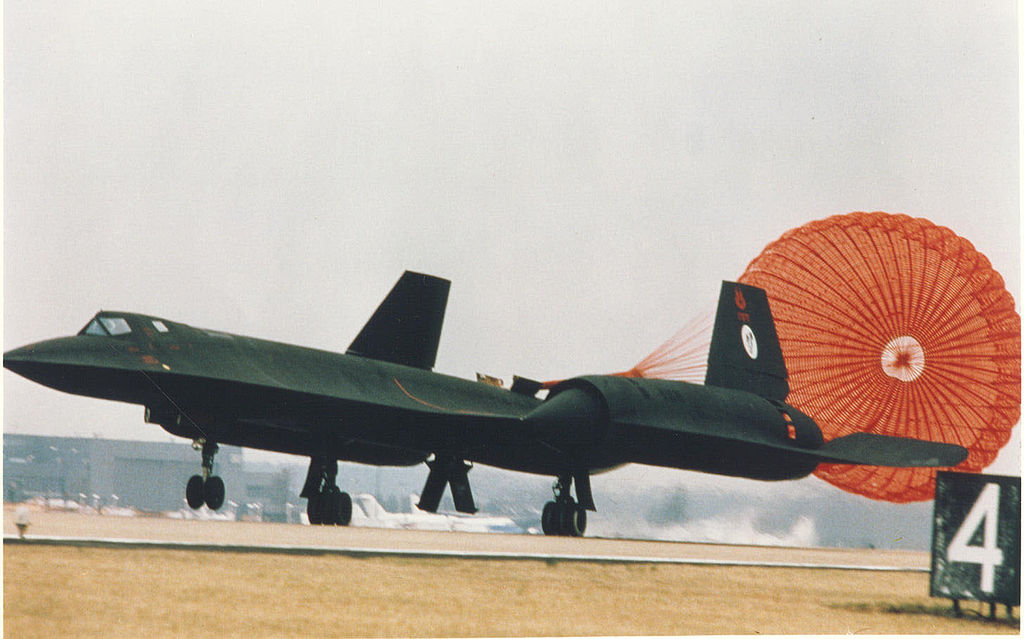

Photo by Lockheed Martin, U.S. Air Force, and NASA