In addition to receiving two Distinguished Flying Crosses and the Air Medal, Lieutenant Colonel Ben Bowles gained one of them for rescuing SR-71 #960

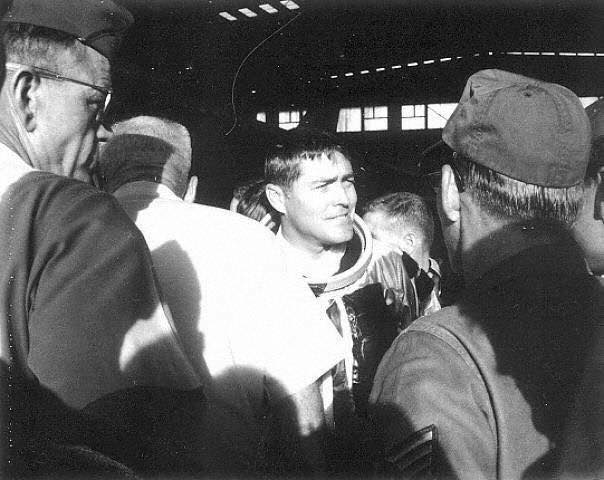

Lieutenant Colonel Ben Bowles, a former SR-71 pilot, passed away on June 1, 2019. His birthday was January 14, 1932. He collaborated closely with Kelly Johnson, one of the SR-71 Blackbird’s five original designers, to create some high altitude/high Mach flight-related advancements. Ben was the first pilot to fly the SR-71 for more than 900 hours while carrying out highly classified reconnaissance missions.

Britt Blaser, former KC-135Q pilot remembers: “I was fortunate enough to serve as a KC-135Q tanker pilot at Beale AFB from 1968–71. We alternated 12 weeks at Beale and 6 at Kadena AB, Okinawa. On my first rotation to Kadena, I was looking forward to renewing a slight acquaintance with Major Ben Bowles, who at that time had more ‘Habu’ hours than anyone. When I reported to the SR HQ, everybody was excited about a picture Ben’s SR had snapped the day before – the nose cone of a SAM directly below, filling the frame of the photo.

But that’s misleading. Since the camera could differentiate patio furniture on a deck, a SAM 40,000 feet below looks huge. But by the time it struggled up to altitude, Ben and Jimmy [Jimmy Fagg who was Bowles RSO] were long gone.

Among other medals, he was awarded the Air Medal and two Distinguished Flying Crosses one of which was for saving SR-71 #960.

As Blaser explains, a couple of months before the SAM photo shoot, Ben had even more fun. This was when the SR program was pretty new and people were still learning things faster than they’d like. On a training mission back in the States, Ben was presented the Air Force “Well Done” award when he saved an SR-71 that experienced an engine explosion “above 60,000 feet and Mach 2.5 while accelerating to a higher airspeed and altitude.”

Bowles describes this particular adventure in an article that appeared on Britt Blaser’s website, Escapable Logic:

“On the morning of 29 July 1968, my navigator, Jimmy Fagg, was not feeling well when we were having our preflight steak and eggs breakfast at the Personnel Support Detachment. Butch Sheffield, returning from leave, walked in and mentioned he needed flight time for pay and that he would gladly substitute for Jimmy.

“The flight was going well. We had just finished refueling and were accelerating thru approx 2.6 Mach and 65,000′, leaving Louisiana heading West. (ed: usually a 40-minute flight to Sacramento) the first indication of a problem was when the right engine “unstarted”. However, this was more serious than a routine inlet unstart.

“I heard a Big Bang and immediately had a big red light (ed: there are no small red lights) I looked through the rear-facing periscope and saw a huge smoke trail: obviously not a contrail.

“Understand, when the inlet is unstarted, the aircraft is experiencing severe aerodynamic buffeting, making it difficult to read instruments until we slow to about Mach 2. The right engine is shut down. I ask Butch for the Engine Fire and the Descent checklist. I declare “Emergency” with the Air Traffic Control center, “descending and diverting to Carswell AFB”. Then I tell Butch to “be ready to bail out”, who responds with, “Oh Shit”! (Butch had punched out of an SR once before and was not anxious to repeat the experience.)

“Butch says, “I wish I had my checklist” (What Butch meant was that he had Jimmy Fagg’s checklist, not his own. Every crew member marks up his checklist with useful margin notes, obviously of great personal value. As a stand-in, Butch was wishing he had his own annotated checklist rather than Jimmy’s, captured on the aircraft’s audio recorder). The roughness is now gone and the machine is flying smoothly with normal control. I tell Butch that I would just as soon stay with her as long as we have good control. Butch concurs (although, the checklist says that if Fire Light does not extinguish… Bail Out). The problem remains, Fire Light is still On, flying on one engine, the smoke has diminished, but is it smoke, fuel spray (we are dumping as much as possible before landing), or contrail? I don’t want to land with fire and Butch concurs. Still difficult to tell if we are trailing smoke due to overcast, poor light conditions, and looking through the periscope is like looking through the barrel of a 22 rifle.

“We elect to request a fly-by with the tower to tell us if they can detect any smoke or fire. The Fire light is still ON. Tower says we look OK. Landing was uneventful. We taxi to and into a designated hanger, stopping inside, shut down the left engine and the hangar doors are closed. We complete the “shutdown checklist”… unbuckle our harnesses and stuff, but no one comes to help us out of the airplane. We at least need a ladder! Butch says the crowd is over by the right wing. Finally, a couple of considerate colonels came to our rescue and advised us, “you may want to see this”. We shuffled around to the right side. The outboard forward section of the nacelle had been blown out, taking with it a portion of the wing’s leading edge. Obvious severe fire damage. Not much of the engine was left in the nacelle… you could see daylight. Lockheed used this accident as a testimonial for titanium airframes. Conventional construction could not have survived the intense heat from the fire…the right outboard wing would have failed rather quickly.”

Bowles left the Air Force in 1972 with the rank of Lt. Colonel, and he later spent 15 years as the Chief Corporate Pilot in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Photo by U.S. Air Force