“As usual in a dogfight, I was tense and excited. I forgot to release the second safety catch for the rockets. They did not go off. I was in the best firing position, I had aimed accurately and pressed my thumb flat on the release button -with no result. Maddening for any fighter pilot,” Adolf Galland

General der Jagdflieger Adolf Galland, one of the key players in the Luftwaffe from 1942 to 1944, was relieved of his duties at the start of 1945. He was soon given the go-ahead to establish Jagdverband 44, his own squadron of Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighters.

He would fly his final mission with this unit, according to Dan Sharp’s book Spitfires over Berlin, as Galland himself wrote in The First and The Last: “On April 26, I set out on in my last mission of the war. I led six le jet fighters of the JV 44 against a formation of Marauders. Our own little directing post brought us well into contact with the enemy. The weather: varying, clouds at different altitudes, with gaps, ground visible in about only three-tenths of the operational area.

“I sighted the enemy formation in the district of Neuburg on the Danube. Once again I noticed how difficult it was, with such great differences in speed and with clouds over the landmarks, to find the relative flying direction between one’s own plane, and that of the enemy, and how difficult it was to judge the approach.

“This difficulty had already driven Lutzow to despair. He had discussed it repeatedly with me, and every time he missed his run-in, this most successful fighter commodore blamed his own inefficiency as a fighter pilot. Had there been any need for more confirmation as to the hopelessness of operations with the Me 262 by bomber pilots, our experiences would have sufficed.

“But now there was no time for such considerations. We were flying in an almost opposite direction to the Marauder formation. Each second meant that we were 300 yards nearer. I will not say that I fought this action ideally, but I led my formation to a fairly favorable firing position.

“Safety catch off the gun and rocket switch. Already at a great distance, we met with considerable defensive fire. As usual in a dogfight, I was tense and excited. I forgot to release the second safety catch for the rockets. They did not go off. I was in the best firing position, I had aimed accurately and pressed my thumb flat on the release button -with no result. Maddening for any fighter pilot.

“Anyhow, my four 30mm cannons were working. They had much more firing power than we had been used to so far. At that moment, close below me, Schallmoser, the jet-rammer [he had accidentally rammed a USAAF P-38 Lightning with his Me 262 in a previous mission], whizzed past. In ramming, he made no distinction between friend or foe.”

Flying in “White 14,” Schallmoser launched his R4M rockets, blowing up one of the B-26s.

Galland wrote: “This engagement had lasted only a fraction of a second – a very important second o be sure. One Marauder of the last string was on fire and exploded. Now I attacked another bomber in the van of the formation. It was heavily hit as I passed very close above it.

“During this breakthrough, I got a few minor hits from the defensive fire. But now I wanted to know definitely what was happening to the second bomber I had hit. I was not quite clear if it had crashed. So far I had not noticed any fighter escort. Above the formation I had attacked last, I banked steeply to the left, and at this moment it happened: a hail of fire enveloped me. A Mustang had caught me napping.”

Technical Sergeant Henry Dietz, a former weapons instructor, had targeted Galland as he attempted to evaluate the harm he had done to his most recent victim after he had been injured by defense fire from one of the B-26s.

Dietz recalled: “Probably the most important thing I remembered from gunnery school was to fire short bursts and forget about the tracer bullets – just use your sights.

“That day, we were flying as flight leaders, and we were about 10 minutes from the target. I flew in the waist position from where I could see all the mechanical parts of the aircraft. I had never seen a jet before. Galland slowed down to the speed of the B-26 so that he could observe and take score. I thought `dummy’. He was flying low, right into the sights of my machine gun. I shot a burst. Nothing happened. A little higher, a little lower, I just kept shooting.”

1st Lt. James Finnegan of the 10th Fighter Squadron, 50th Fighter Group, the pilot of a Republic P-47 Thunderbolt escort fighter, had also spotted Dietz as he opened fire on Galland’s aircraft.

Finnegan later remembered: “I was leading the top cover of P-47s that was escorting the B-26s to their target. As I gazed down I saw two objects come zipping through the formation, and two bombers blew up immediately.

“I watched the two objects go through the bomber formation, and thought ‘That can’t be a prop job, it’s got to be one of the 262 jets’. I was at about 13,000ft and estimated them to be at about 9000-10,000. They were climbing, and I pulled a split-S toward the one that turned left, and almost ended up right on top of him – about 75 yards away.

“I gave a three-second burst and saw strikes on the right-hand engine and wing root. I was going so fast, I went right through everything, and guessed my speed at about 500mph. I recorded it as probable. I was flying a D-model Thunderbolt with a bubble canopy, a natural metal finish, and a black nose. The 262 had green and brown mottled camouflage with some specks of yellow. That turned out to be my last flight in a P-47.”

Galland wrote: “A sharp rap hit my right knee. The instrument panel with its indispensable instruments was shattered. The right engine was also hit. Its metal covering worked loose in the wind and was partly carried away. Now the left engine was hit too. I could hardly hold her in the air.

“In this embarrassing situation, I had only one wish: to get out of this crate, which now apparently was only good for dying in. But then I was paralyzed with the terror of being shot while parachuting down. Experience had taught us that we jet fighter pilots had to reckon on this. I soon discovered that my battered Me 262 could be steered again after some adjustments.

“After a dive through the layer of cloud, I saw the Autobahn below me. Ahead of me lay Munich and to the left Riem. In a few seconds, I was over the airfield. It was remarkably quiet and dead below. Having regained my self-confidence, I gave the customary wing wobble and started banking to come in.

“One engine did not react at all to the throttle. I could not reduce it. Just before the edge of the airfield I, therefore, had to cut out both engines. A long trail of smoke drifted behind me. Only at this moment, I noticed that Thunderbolts in a low-level attack were giving our airfield the works.

“Now I had no choice. I had not heard the warnings of our ground post because my wireless had faded out when I was hit. There remained only one thing to do: straight down into the fireworks. Touching down, I realized that the tyre of my nosewheel was flat. It rattled horribly as the earth again received me at a speed of 150mph on the small landing strip.

“Brake! Brake! The kite would not stop. But at last, I was out of the kite and into the nearest bomb crater. There were plenty of them on our runways. Bombs and rockets exploded all around; bursts of shells from the Thunderbolts whistled and banged.

“A new low-level attack. Out of the fastest fighter in the world and into a bomb crater, that was an unutterably wretched feeling. Through all the fireworks an armored tractor came rushing across to me. It pulled up sharply close by. One of our mechanics. Quickly I got in behind him. He turned and raced off on the shortest route away from the airfield. In silence, I slapped him on the shoulder.

“He understood better what I wanted to say than any words about the unity between flying and ground personnel could have expressed.

“The other pilots who took part in this operation were directed to neighboring airfields or came; into Riem after the attack. We reported five certain kills without loss to ourselves. I had to go to Munich to a hospital for treatment of my scratched knee. The X-ray showed two splinters in the kneecap. It was put in plaster. A fine business.”

Oberstleutnant Heinz Bar took over operational command of JV 44 with Galland now out of commission and Steinhoff still in the hospital (he was hurt in an accident on takeoff with his Me 262 on April 16). The unit was given orders to go to Salzburg-Maxglan on April 28. There, it was to conduct operations from woodland positions alongside the Munich-Salzburg Autobahn. This turned out to be JV 44’s last move.

On May 4, as the Americans closed in, the unit destroyed its Me 262s by placing grenades in their engine intakes. The remaining pilots were apprehended and brought in for interrogation. The following day, Galland submitted to American forces and JV 44 was no more.

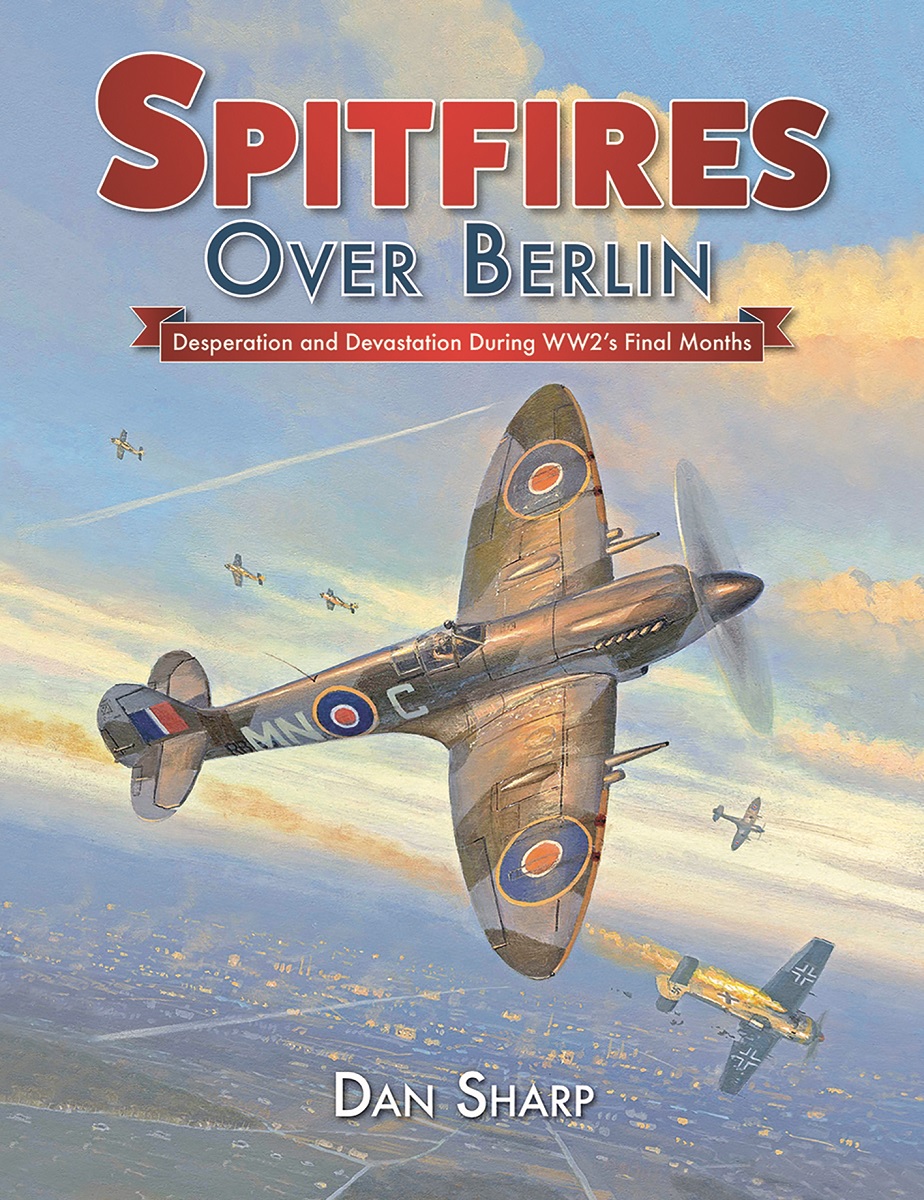

Spitfires Over Berlin is published by Mortons Books and is available to order here along with many other beautiful aviation books.

Photo by U.S. Air Force Noop1958 and German Federal Archive via Wikipedia