Lt. Cmdr. Wang Wei, the pilot of the Chinese J-8 interceptor, and the aircraft were lost, while the damaged US Navy EP-3 made an emergency landing on Hainan Island

A People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) J-8II interceptor and a US Navy EP-3E Aries II (BuNo 156511), both assigned to VQ-1, collided over the South China Sea 110 kilometers off the island of Hainan on April 1, 2001. When the damaged US aircraft made an emergency landing on Hainan Island, the Chinese jet and its pilot, Lieutenant Commander Wang Wei, perished. Before landing, the crew destroyed as much sensitive information as they could.

This incident would turn out to be both Wang Wei’s final flight and the beginning of the mythic figure he would become.

Wang, a squadron leader in the 22nd Regiment of the 8th PLA Naval Air Force Wing stationed in Lingshui, was described in an article published in Air Force Magazine on July 1, 2001. He was believed to be 33 years old.

As seen by a video of an aerial encounter that happened on January 24, 2001, and was made public in Washington, Wang was no stranger to intercepts. His J-8 was seen flying within 20 feet of another EP-3E during the mission and reducing its speed to the point where it was finding it difficult to fly alongside the EP-3E. The Chinese military also supported the US claim that Wang and a different pilot were in control of the two J-8s involved in the incident on January 24.

On April 1, 2001, while US Navy Lt. Shane Osborn had his plane on autopilot and was flying level at a speed of about 180 knots, the 23 crew members of the EP-3E carried out their duty, with the majority of them doing electronic vacuum cleaning of all communications along China’s coast.

“We were obviously being intercepted,” said Osborn, “and the [Chinese] aircraft was approaching much closer than normal, about three to five feet off our wing. So, I was just guarding the autopilot, listening to the reports from the back end and from my other pilot, Lt. [Patrick] Honeck, who was in the window watching the aircraft approach.”

Osborn went on, “The aircraft made two close approaches, [with the pilot] making gestures. And then, on the third one, his closure rate was too high, and he impacted the No. 1 propeller, which caused a violent shaking in the aircraft. And then, his nose impacted our nose, and our nosecone flew off, and the airplane immediately snap-rolled to about 130 degrees in the low bank and became uncontrollable.”

Osborn told CNN he had had “eyeball-to-eyeball” contact with Wang: “I did on the second time he joined up on us. He came out a little bit front and was making gestures, and we could all see him.” What kind of gestures? “I don’t care to comment on that,” Osborn said.

He later recalled, “He had his oxygen mask off and was waving us away and mouthing some words.” However, he could not tell what Wang was saying.

Lt. John Comerford, the EP-3E crew member who got the best look at Wang’s deadly flying, told CNN. “I was actually out of my seat and kind of down on my haunches, looking out of the port side, left side, over-wing exit window at the fighter as it approached. I was taking notes on a clipboard about the condition of the flight and things like that and was watching the approaches that he was making to our plane.” After the impact, Comerford was knocked backward and trapped to the ground as the plane overturned.

China gave a very different account. Wang’s co-pilot in the F-8, Zhao Yu, provided the following testimony to Liberation Army Daily:

“I saw the head and left wing of the US plane bump into Wang Wei’s plane. At the same time, the outside propeller of the US plane’s left wing smashed the vertical tail wing of the plane piloted by Wang Wei into pieces. I reminded Wang Wei, ‘Your plane’s vertical tail has been struck off. Pay attention to remain in condition, pay attention to remain in condition.’ Wang Wei replied, ‘Roger.’ About 30 seconds later, I found Wang Wei’s plane rolling to the right side and plunging. The plane was out of control. Wang Wei requested to parachute. I replied: ‘Permission granted.’ Afterward, I lost contact with Wang Wei.”

The Chinese government claimed that the EP-3E slowed down, making it difficult for the jets to fly alongside and shake the intercepting aircraft. Liberation Army Daily also stated that the surveillance aircraft would make sudden movements. “The wild and arrogant planes also often jumped up and down and suddenly turned steep left and right to provoke the pilots of our side again and again with extremely dangerous actions.”

Osborn denied China’s assertion that the EP-3E abruptly turned and hit Wang’s aircraft.“It’s not very common for a big, slow-moving aircraft to ram into a high-performance jet fighter,” he said. “And we definitely made a sharp left turn. That was called uncontrolled flight-inverted in a dive after he impacted my propeller and my nose.”

Wang was getting ready to “thump” the EP-3E by passing in front of the slower plane and activating his jet’s afterburners, according to Osborn and other Pentagon officials. The action is a hostile gesture intended to disrupt the target aircraft’s flight. But because the planes collided, he was unable to perform any thumping. Osborn’s first response to the crash was matter-of-fact. “The first thing I thought was, ‘This guy just killed us,’ ” he recounted later, noting that he remembered looking up and “seeing water” close up-an unhappy sight for any pilot.

“He was joining up on us and had too high of a closing rate, and instead of going low, he went up,” Osborn said in an interview while speaking of the ordeal and the encounter with Wang. “He could have shot underneath us and never hit anything.”

Zhao Yu claimed he came within 9,000 feet of the sea while flying and saw Wang’s airplane wreckage, as well as a stabilizing parachute for the flight seat and a rescue parachute that was “floating in the air.” Zhao touched down at Lingshui at 9:30, and the damaged EP-3 showed up around 9:40.

Both US and Chinese versions described a significant search effort by the Chinese government. Almost 52,000 square miles of water were covered during the roughly 10-day effort. Together with more than 55,000 participants, there were about 110 planes, more than 100 ships, and at least 1,000 more ships, including fishing boats, civilian boats, and salvage ships.

The U.S. was forced to pay to have the plane disassembled and moved when the Chinese refused to let it be flown off the island. The Chinese also demanded $34,567.89 from the United States to cover the cost of the 24 crew members’ lodging and food for 11 days.

Instead, the Communist regime in Beijing capitalized on Wang’s passing by launching a propaganda effort to glorify the fallen fighter pilot and castigate the US on the pretext of combating “hegemonism,” the term Beijing used to refer to US strength and influence in the Pacific.

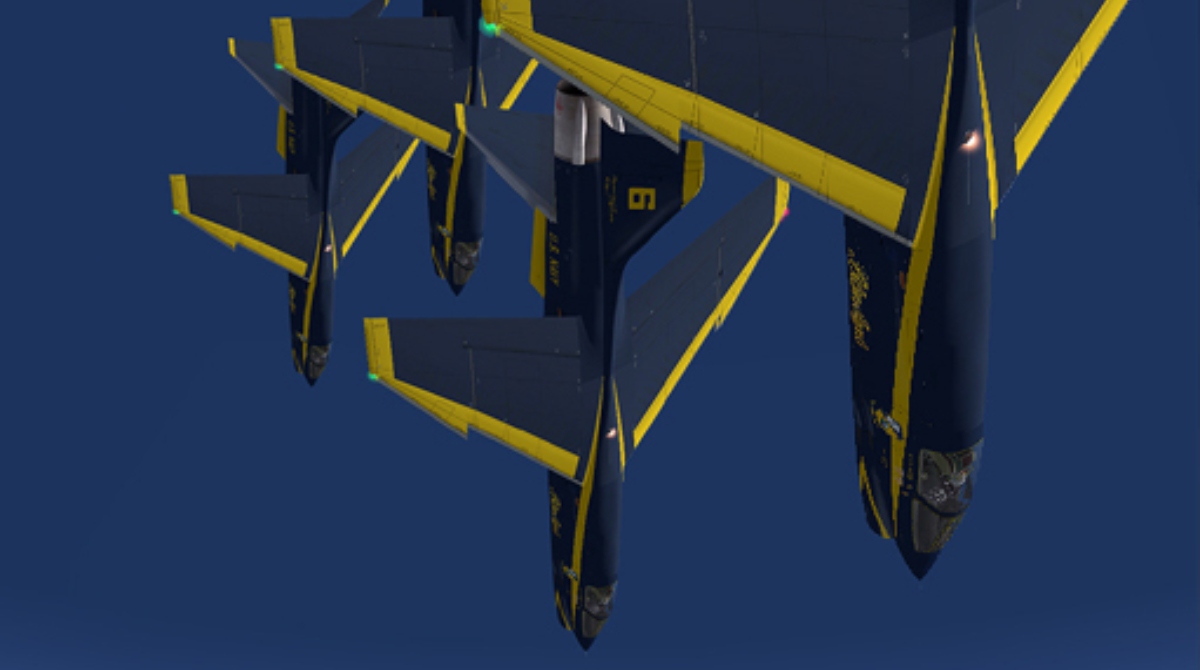

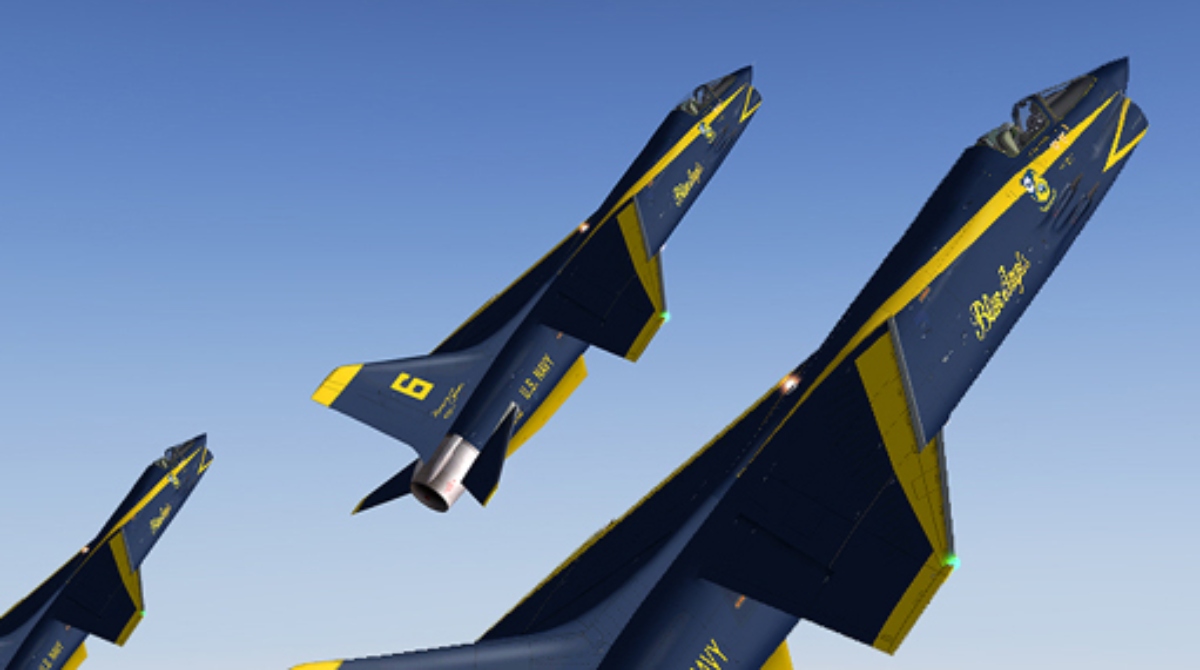

Photo by U.S. Navy