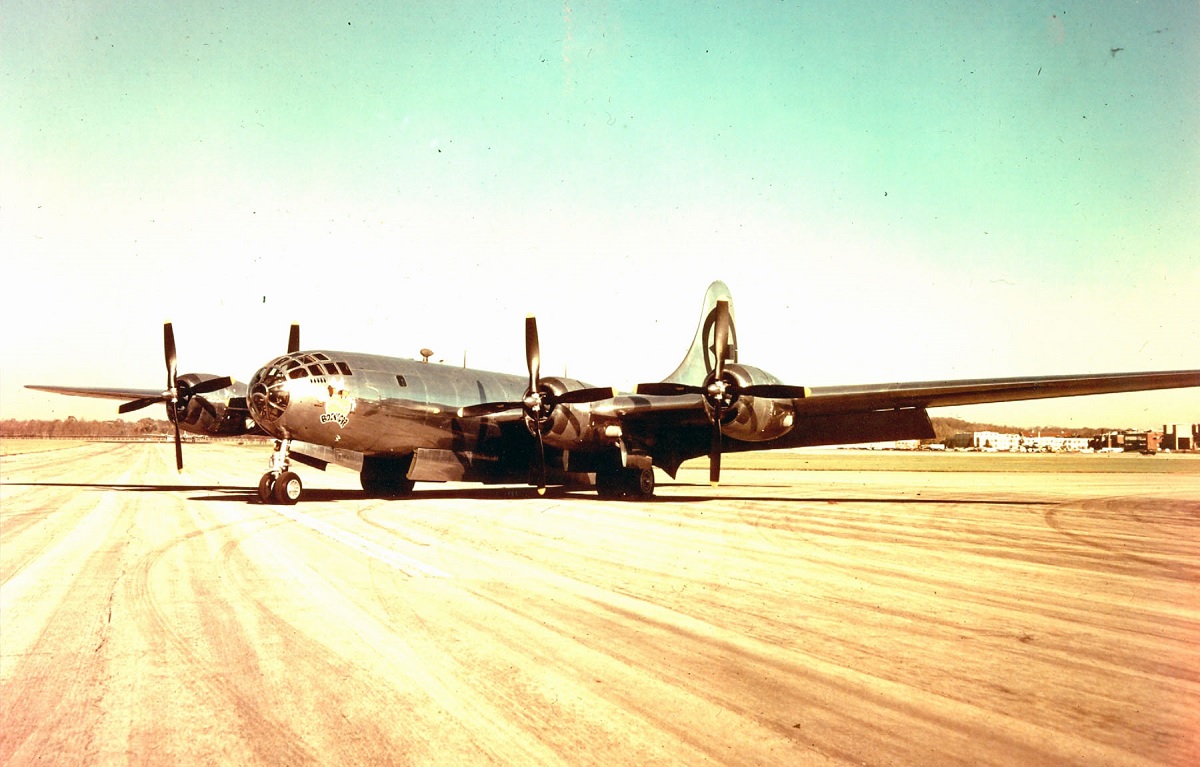

The B-29 saw most of its action in the Pacific theater of World War II. How would the B-29 have fared in the air conflict over Germany if it had been made available in 1943?

The first B-29, designed in 1940, took to the skies for the first time on September 21, 1942, replacing the B-17 and B-24. The Superfortress was deployed to Asia in December 1943 by the U.S. Army Air Forces leadership, where its tremendous range made it especially well-suited for the lengthy over-water flights against the Japanese homeland from bases in China. B-29s started attacking Japan from the islands of Saipan, Guam, and Tinian in the final two months of 1944.

Hence, the B-29 saw most of its action in the Pacific Theater of World War II, but how would it have fared if it had been made available in 1943 and engaged in the air conflict over Germany?

‘The short answer is I don’t think it would have been very effective in 1943, and in fact may have been a deathtrap over Europe, with higher losses than the B-17 or B-24,’ Willard Foxton, an Aviation Expert who made several World War II documentaries, explains on Quora.

‘Essentially there are three reasons –

‘1.) Technological immaturity;

‘2.) Bad USAAF doctrine in 1943 over Europe, which is especially bad for the B-29;

‘3.) The Luftwaffe’s excellent home defense system is far better than the Japanese equivalent.

‘I’ll deal with each in turn, but let’s start with Technological Immaturity.

‘Here’s a harsh truth – the B-29, while a revolutionary aeroplane, was not a very good aeroplane as originally deployed, and these problems would certainly be present in a version deployed in Britain in 1943.

‘Curtis LeMay – the commander of the Superfortress force – said of it “There were scores of defects – either readily apparent – or worse- appearing when an aircraft was actually at work and at altitude”.

‘The Superfortress was incredibly expensive – developing it cost a billion more than the atomic bomb – and it crammed in so many advanced systems, all at the cutting edge of technology, that very few things in it worked perfectly.

‘More Superfortresses were lost to mechanical failure than any other cause; in its first 6 months, regularly 10% of bombers that took off would be lost – per mission – to mechanical defects alone.

‘In particular, its R3350 engines – while incredibly impressive on paper, and the most powerful fitted to a WWII bomber – were very unreliable all through the war, especially when the fortress was first deployed.

‘Engine fires and overheating were very common because of the “double stack” cylinder configuration, often leading to engine temperature as high as 300 degrees; this might have been manageable were it not for the unique construction material of the engine.

‘To save weight the R3350 had a magnesium crankcase. You might note now – this is the last example of magnesium being used in aircraft engine construction, for a reason!

‘While magnesium is light and very strong, it’s also highly flammable, and once on fire, almost impossible to extinguish. In 87% of engine fires, the onboard extinguishers were unable to cope, and the fire would burn out the whole engine and wing. The loss stats speak for themselves – of 414 B-29 losses in WWII, 147 of them were to flak and Japanese fighters, 267 to engine fires.

‘Apparently, the fires were an incredible sight to behold – the magnesium burned blindingly bright with a core temperature approaching 5,600 °F (3,100 °C) – and were so intense the main wing spar could burn through in seconds, resulting in catastrophic wing failure.

‘The magnesium was also surprisingly brittle; reports often describe engines starting and shaking themselves to pieces on the runway, and they did not handle damage well.

‘The bulk of these losses were early in the campaign of bombing Japan when the B-29s were flying from China; the problems were eventually ameliorated, but largely because of a doctrinal shift to flying slower and lower.

‘The defensive suite is another likely problem for the European B29; the B29 was fitted with a state-of-the-art suite of 4 remote controlled gun turrets, and a manned tail turret with a 20mm cannon. Linked to 5 networked computerized gunsights the gunners were, in theory, able to shoot with amazing accuracy and even control multiple turrets at once.

‘Sounds great, right? But the problem was the system simply didn’t work. It often failed to keep Japanese fighters at bay and was absolutely plagued with mechanical and technical glitches.

‘Notably the frontal guns – doubled from 2 to 4 to prevent frontal attacks -had very poor ballistics as a compromise for streamlining, leaving a 4-gun turret where it was ballistically impossible to hit a target with more than two guns, with a large blind spot to head on attack.

‘The 200lb CFC computers suffered from terrible build quality and rarely worked as advertised – a common glitch was for the turret to slew 20 degrees and then wildly spray its entire ammunition load in that direction. This fault – caused by bad wiring design – was only tracked down and fixed in January 1945, when the Superfortress had been in action for seven months.

‘A late upgrade enabled you to set the turrets to track motion – a great setting in theory, until in raids over Japan 17 bombers had their bomb-bays riddled with bullets on the bomb run – opening the bomb doors had triggered other bombers in their formations automatic turret fire.

‘The turrets were also impossible to access in flight – so any malfunction or jam could not be repaired in the air. The impressive tail turret fit – with 20mm cannon – was hampered by bad ballistic design so the two machine guns and the cannon could not hit the same target, and the radar guiding of the tail cannon never functioned in combat (eventually the tail cannon & radar were deleted, and the twin .50 cals remained).

‘Ultimately the defensive system was so unsatisfactory that it was removed from all aircraft in February 1945 (bar the tail turret), and the B-29B was built without any turrets at all, as by then the USAAF had realized defensive guns on a bomber – even super advanced defensive guns – were less useful than flying high and fast and at night.

‘Which takes me on to…

‘Bad Doctrine

‘In 1943, the USAAF was wedded to a bad doctrine – the self-defending bomber formation that would fight its way to the target without an escort in daylight.’

Foxton continues:

‘Had the B-29 been deployed in 1943, it would have been deployed like this, and I suspect that despite its speed and altitude advantages, it would have been slaughtered in some kind of disastrous, disappointing deep penetration raid in the Schweinfurt/Ploesti mould (to be fair, like all other attempts to fly self-defending bombers hundreds of miles to defended targets).

‘The B-29 – as such a revolutionary aeroplane – also had a huge crew training problem. There were no experienced instructors because the experience of the type and the conditions it flew in were literally non-existent and at the edge of human experience -so many crews passing the test to fly it were actually very poor. This problem was so bad that even the notoriously hard-assed Le May stood down the entire B-29 force in the Pacific for retraining for several months.

‘Part of this failure of crew training was that atmospheric conditions were also against the B-29 being flown as initially imagined. The US doctrine was formation flying and precision bombing, that was how the initial crews were trained.

‘The B-29 flew sufficiently high that a new phenomenon – 140 mph winds at high altitude, that we now know as “the jet stream”- made formation flying almost impossible and one gust could shatter the mutually supporting defensive boxes US doctrine relied upon. So not only was the core US flying training obsolete but crucially – and unbeknownst on its initial deployment – bombing accuracy with the B-29 initially deployed was woeful. Bombs were dropped into 100 mph+ winds at high altitudes with predictably unpredictable results, rendering the Norden bombsight – the center of USAAF precision bombing doctrine – utterly useless.

‘In 1944, only 1 in 3 B-29s was getting a hit by RAF standards, ie within 5 miles of the aiming point. In daylight, in clear visibility. The truth was it took a painful experience to realize the doctrinally prescribed bombing height of 27–30,000 feet was completely impractical.

‘On top of this, the B-29 in this counterfactual 1943 deployment offers a unique and exciting opportunity to allied commanders. Sure, you COULD deploy it alongside the B-17 and B-24, but then you are sacrificing the incredible technological advantages the B-29 brings.

‘While the B-29 had huge advantages over the B-17 and B-24, it wasn’t so good it was invulnerable to German fighters, particularly in its early configuration with full guns. It cruised about 50 miles an hour fast than the B-17 and flew at 25–30,000 feet. It’s only once you take the turrets off it starts to power up beyond 35,000 feet where fighters severely lack energy.

‘As late as September 1944, when Colonel Paul Tibbets suggested taking the turrets off the B-29 to get higher and thus safer, with the devastating losses over Europe, and the disappointing performance of the B-29 up til that point, LeMay *still* had him checked out by a psychiatrist for combat fatigue before acceding to Tibbets’ request for a test. In 1943, any suggestion to take off the guns or run with an escort – measures that *would* have made the B29 viable – would have been simply rejected out of hand.

‘The USAAF was determined to test the theory of self-defending bombers literally to destruction, and the B-29 in its full turret configuration was the great white hope of this theory.

‘In particular, the range, speed, and promised technological “invulnerability” of the B-29 would have encouraged the 8th air force’s commanders to try for very long raids with it – raids the B-17 and B-24 simply couldn’t do.

‘As we’ve already seen, the CFC gun system was highly unreliable, and self-defending bombers don’t really work, but the point is nobody knew at the time. The B-29 would definitely have been tried on deep penetration raids solo, without escort.

‘The trouble with these raids would be that as well as exposing the B-29’s mechanical and defensive shortcomings, it would also create situations where 70–80 B29s (typical raid size for first six months of B-29 combat career) would be fighting practically the whole German air defense network, a sure-fire recipe for a massacre.

‘Which takes me to…

‘The Luftwaffe’s prowess’

As Foxton explains, ‘While raids at the 70–80 aircraft scale were semi-successfully carried out in the Pacific – albeit often with a ~10{4b4a8f7af628fb0b180f961b7ba32842c69b81c2d3374171931aa15051caf1c9} loss rate from mechanical failure – they were successful because the Japanese in Burma had no radar, no aircraft able to reliably fly high enough to engage the B-29 and very few guns able to shoot high enough to engage the aircraft.

‘That would simply not be the case in 1943 over Europe.

‘There’s a huge difference between flying from a base in China to a target in China, over contested territory, against an enemy with no early warning and no effective defense, to flying over a continent totally dominated by the enemy with industrial grade flak defenses and hundreds of interceptors capable of reaching you, who know which way you are coming and going (interesting fact – the US lost more bombers coming home from raids than on the way in, as the routes were much more predictable).

‘The Japanese lacked a mass of aircraft with 2 stage superchargers able to get high enough to engage the B-29 and cannon armament to bring it down; Japanese aircraft that could get high enough often emptied the rifle-Calibre guns they were armed with and got B-29 kills by ramming (indeed the B-29 in the picture above was brought down by being rammed by a Ki-44)

‘The Luftwaffe had no shortage of aircraft with superchargers to get high up, with both standard day fighters of the Luftwaffe – the FW 190 and Bf 109 – coming equipped with superchargers and cannon-armed as standard. Either was capable of reaching the operational altitude of the B-29 with a combat load and hitting it with the 20mm or even 30mm cannon rounds that had a much better chance of a kill on a big bomber.

‘Going back briefly to the technological problems of the B-29 – as a result of its design, it was paradoxically more vulnerable to cannon fire than the B-17 or B-24. It was the first pressurized bomber, so cannon hits on it often caused explosive decompressions of the cockpit.

‘This – while less spectacular than the James Bond “sucked out of a hole” decompression of Hollywood – was nonetheless deadly and horrifying to crews, wrecking visibility as the aircraft fills with fog, and posing huge risks of oxygen deprivation to crews.

‘By Korea, there was a drill for this, which included teaching pilots to “pressure breathe” in order to avoid passing out, but the problem was barely recognized until the B-29 had been in service for some time – part of the problem with a 1943 deployment of the B-29 would be this sort of thing – which was worked out in low-intensity combat over China and Burma – would be happening in an incredibly harsh, contested airspace environment.

‘I also dread to think what regular exposure to cannon fire and massed flak would do to those highly flammable engines, especially once the Luftwaffe – who were great at analyzing bombers for weak points – figured out how vulnerable the engines were. I think there’s every chance a European-deployed B29 would be regarded as an incredibly costly failure, a hugely hubristic example of US technical overreach.

‘Finally, the real fix for the B-29 was the acceptance that it was *not* an effective high-level, high-speed bomber (without an atomic bomb, at least). What it was, was an incredibly effective, very long-range, very heavy load-carrying bomber.

‘The most effective conventional B-29 raids were carried out at about 5,000 feet, dropping incendiary bombs on Japanese cities. Bringing down both speed and altitude massively helped with the engine trouble, and by this point, Le May had removed the troublesome defensive armament.

‘These raids were possible against a much-weakened 1945 Japan, with no effective night fighter counter, very poor airborne interception radar, and lacking the extraordinary levels of low-level light flak present in Germany in 1943. Even against the far less deep air defenses of North Korea in the Korean War, the B-29 could not operate without an escort by day, or by night at a low level.

‘So, even if a doctrinal switch in 1943 *was* possible, the conditions to use the B-29 in its most effective configuration simply do not exist.’

Foxton concludes:

‘In conclusion, while I concede the B-29 was a revolutionary aircraft and technological wonder, it contained several technological dead ends (magnesium engines and remote gun turrets), and a 1943 deployment against the Luftwaffe at its peak would show up these flaws in absolutely catastrophic ways.

‘Ultimately, I think like the P-38 Lightning, the B-29’s success in the Pacific is as much a reflection of the poor quality of Japanese aircraft after 1942 as much as it is a reflection of US technical superiority.’

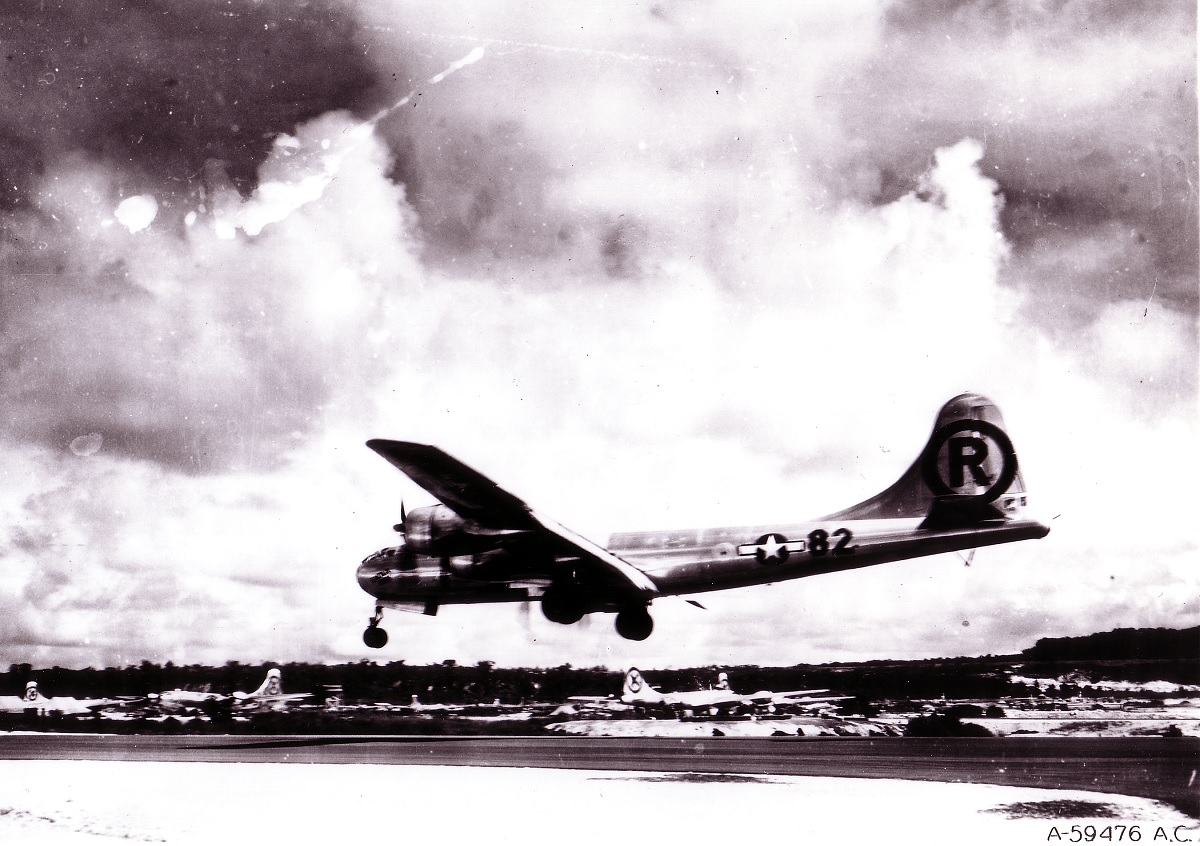

Photo by U.S. Air Force