For the Brits, the loss of Force Z was a catastrophic setback that essentially signaled the end of their empire in the East

Britain’s empire in Southeast Asia was in danger as the threat of war with Japan loomed in the latter part of 1941. The modern battleship Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser Repulse were part of the British government’s decision to send Force Z, which was intended to boost Singapore’s naval defenses and act as a potent naval deterrent against Japanese assault.

These two powerful ships arrived in Singapore on December 2, five days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, as described by Angus Konstam in his book Sinking Force Z 1941 the day the Imperial Japanese Navy killed the Battleship. But more importantly, they had no air cover. Force Z’s approach was discovered by Japanese scout aircraft on December 9 in the Gulf of Thailand. Battleships at sea could maneuver and had ready anti-aircraft defenses, unlike at Pearl Harbor. But it was useless. The combat was unequal since the Imperial Japanese Navy’s (IJN) dive and torpedo bombers were the most sophisticated in the world.

A torpedo strike crippled HMS Prince of Wales at 11:44 that morning. She was difficult to steer a straight course, listing considerably to port, and her speed had dropped to 16 knots. Due to the list, any torpedo strikes on her starboard side would have a fair chance of striking her below her protective armored belt because her lower hull was riding high in the water. The Prince of Wales was therefore very exposed.

Several Japanese planes were then seen flying toward the battleship from the south around 12:20 hours. Admiral Phillips took some time to recognize he was under torpedo attack as he watched their attack unfold from the ship’s compass platform. But it soon became apparent that this was indeed what was going on. The battleship’s forward 5.25-inch batteries could not depress low enough to fire at the incoming low-flying aircraft because of the list.

Due to a shortage of electricity, her after batteries were no longer functional. Only the ship’s smaller guns and multiple-barreled “pom-poms” offered any real resistance. The battleship’s starboard side was approached by the first six Type 1 bombers of the 1st and 2nd squadrons, Kanoya Kokutai, who launched their torpedoes at a close range of about 500 meters. Three of them hit the Prince of Wales in three different places—forward, amidships, and aft—resulting in significant flooding and permanent damage. These fatal blasts caused the battleship to slowly start sinking.

The remainder of the Kanoya Kokutai split off from the assault on the Prince of Wales at 12:24 a.m. and started running toward the Repulse, which was off their port side. To assault the battle cruiser simultaneously from multiple angles, they encircled her. Repulse avoided most of these torpedoes. However, one hit Repulse on her port quarter, damaging her outer port propeller shaft and causing flooding.

The 3rd Squadron, Kanoya Kokutai, approached the battle cruiser simultaneously at 12:25 on both the port and starboard sides. Repulse struck by four more torpedoes, three on her port side and one to starboard. The battle cruiser started to sink and heel over as a result of the severe flooding damage these inflicted. The command to abandon the ship was given. The Repulse sank at 12:32.

Prince of Wales was struck amidships by a 500 lb bomb at 12:41 by the 1st and 2nd squadrons of Mihoro Kokutai, resulting in significant casualties. On the Prince of Wales, the order to leave the ship was given at 13:10, and at 13:23, the ship sank.

The British suffered a catastrophic strategic setback with the loss of Force Z, which essentially signaled the end of their empire in the East. But more significantly, the sinking signified the end of the era in which battleships were regarded as the ocean’s rulers. From that point on, naval warfare would be decided by air power rather than big guns.

Sinking Force Z 1941 the day the Imperial Japanese Navy killed the Battleship is published by Osprey Publishing and is available to order here.

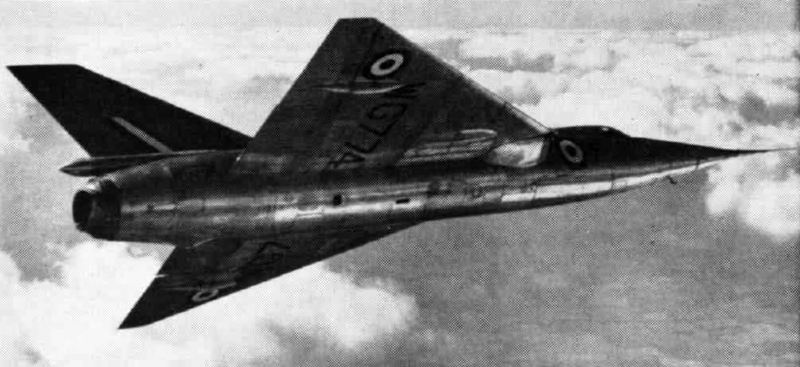

Photo by Adam Tooby via Osprey