However, if it had been put into production more quickly, the BV 155 might have proven valuable in battling the most modern, high-flying Allied reconnaissance aircraft

Through the pages of American magazines and newspapers, which seem to have had no qualms about printing sensitive details that other countries may have tried very hard to keep secret, German intelligence was able to closely monitor advances within the US aircraft industry throughout 1941.

The Consolidated B-24D Liberator was to be fitted with a pressure cabin for high-altitude operations, as reported in Model Airplane News of August 1941, according to Dan Sharp’s account in his book Blohm & Voss BV 155. This information was included in the Auslandsnachrichten des General-Luftzeugmeisters Dienst Nr. 3/41/1 (Reichsluftfahrtministerium, RLM, intelligence briefing on other countries’ aircraft developments) for September 1, 1941. In a similar vein, a July 1941 article from Aviation, which was mentioned in the same document, openly described Boeing’s efforts to develop a three-man pressurized cabin for use over 12 km, the service ceiling of the most recent Bf 109 variants.

Since the Luftwaffe would soon face enemy bombers it had no chance of stopping, there was apparent anxiety when America joined the Second World War on the side of Britain and the Allies in December 1941. The RLM began looking for a new high-altitude fighter in the spring of 1942 as a result of these worries. A higher peak altitude provides a natural advantage in air-to-air combat, so Messerschmitt and Focke-Wulf had already been working to increase the service ceiling of their standard fighters. However, the RLM wanted them to go beyond simply modifying their existing designs with a pressure cabin and longer wings.

Focke-Wulf is another story. Messerschmitt concentrated on preliminary work being done with Daimler-Benz on the new DB 628 engine, which is a DB 605 with a two-stage supercharger for enhanced performance at high altitude. DB appears to have been responsible for the majority of the work, employing a Bf 109F airframe with the manufacturing code “Me 409.”

The Bf 109’s narrow track undercarriage, which was sometimes considered to be its major fault, was also being worked on at the same time. The improved Bf 109G airframe and new wings with gear that folded inwards were included into the Me 409 design, and it was given the official RLM designation Me 155. (8-155). Three new aircraft were planned to be built on it: a normal fighter to compete with the Me 309, a high-altitude fighter to take on those American bombers, and a carrier-based fighter to take the place of the Graf Zeppelin’s outdated Bf 109E-based Bf 109T.

The Me 409/Me 155 project was assigned to the French subcontractor SNCAN since Messerschmitt was already operating at full capacity on other projects. However, it appears that SNCAN was short on time and the Me 155 was placed to the back of the line.

It appears that Messerschmitt was equally and unsurprisingly uninterested in the type. After the initial fear of American bombers subsided, there was little continued interest in a high-altitude interceptor. However, there was some profit in the carrier-based version, or so it seemed until the Graf Zeppelin was canceled. Re-engineering the Bf 109G, giving it straightforward rectangular inserts to enlarge its wingspan, and leaving its undercarriage in place as the Bf 109H made it simpler to complete the same task. Early in 1943, production on the Me 155 in all its forms was stopped.

It was required to offer a high-altitude option in the form of the Me 209H when the Me 309 was scrapped and the Me 209 was chosen as the intended replacement to the Bf 109. By January 1943, a fundamental component of Messerschmitt’s design philosophy (and that of the majority of other German aircraft manufacturers) was to specify the highest percentage of existing components for new types in order to prevent supply chain disruptions and production output. As a result, the Me 209 was mainly based on the Bf 109G but had a redesigned tail, wings with inward-retracting landing gear similar to the Me 155, and a new engine in the shape of the Jumo 213.

When the RLM judged that a normal fighter modified to fly at 12 km with a ceiling of about 13 km was insufficient, the situation altered in May 1943. Despite the fact that the Bf 109H and Fw 190H (Ta 152H after August 1943) were both high-altitude fighters, the RLM required something with a 16km range.

Early in 1943, the British began equipping their newest reconnaissance aircraft, including the Spitfire PR Mk. XI and Mosquito IX, with the two-stage supercharged Merlin 61, making them inaccessible to most German interceptors. In addition, a Spitfire (likely a Mk. VI modified with a pressure cabin) had been found in Dieppe after the disastrous Operation Jubilee raid on the French coast on August 19, 1942, according to information presented at a meeting of the RLM’s GL-Besprechung on September 1, 1942.

Apart from the fact that the Americans had yet to have any significant influence in the European theater, it was obvious that the British were also now developing a worrisome high-altitude capability. Therefore, the RLM asked Messerschmitt to look into the viability of a machine with a 16 kilometer peak altitude. In response, the company developed the three-stage P 1091 project, the first step of which was the most recent Bf 109H version.

The two concepts that survived were promptly added to the increasing list of projects that Messerschmitt still lacked the genuine capacity to work on. The RLM liked the first and third stages but saw no need for the second. Generalfeldmarschall Erhard Milch took the unconventional step of stopping the production of Blohm & Voss’s trio of seaplanes, the BV 138, 222, and 238, and giving that company’s design and production capacity to Messerschmitt because the company needed more resources but none could be obtained through conventional channels. This was perhaps a wise decision given that Blohm & Voss’ excellent staff was squandered on maintaining equipment that, by this stage, was mostly unnecessary for the Luftwaffe.

Messerschmitt could have chosen to give B&V any of its work — aspects of the Me 262, work on the Me 410, further development of the Me 163, the still-viable Me 209, or even the Me 264 bomber but instead, the company handed Blohm & Voss the P 1091 Stage 3. On September 9, 1943, the contract was finalized and the project was given the official name Me 155B; there was never a ‘A’.

This was consistent with Messerschmitt, where the “A” did not exist until the “B” did. Before the Me 163B and Me 328B gained their official names, the Me 163A and Me 328A were only projects and prototypes. The Me 163B and Me 328B are now known as the Me 163A and Me 328A, respectively.

Even though the partnership between Messerschmitt and Blohm & Voss got off to a good start, the B&V team doesn’t seem to have realized what a massive operation Messerschmitt AG was or how little time the firm had to watch over them during the project’s early phases. The Blohm & Voss team was outraged and upset when the location of a conference was changed at the last minute, and they went to the wrong place. Hermann Pohlmann recounted this incident vividly in Thomas H. Hitchcock’s Monogram Close-Up 20 Blohm & Voss 155, Monogram 1990.

Due to this mix-up, B&V complained quite petulantly to the RLM, who then complained to Messerschmitt, and the relationship between the two businesses was soon in ruins. After Blohm & Voss’s cooperation ended in February 1944, the aircraft type was given their initials: BV 155B. The five BV 155B prototypes that B&V had purchased were difficult to manufacture because the type’s RLM priority rating was set too low. But it did find time to alter its radiators, making the prototypes obsolete even before they were constructed.

As 1944 went on, the Allied bombing of Germany reached a fever pitch, and the Luftwaffe’s principal concern changed to preventing the bomber streams. This seems to have once again turned the spotlight on the 8-155 and its priority was evidently increased, with an order being placed for 30 examples of the new BV 155C. With a Luftwaffe pilot at the controls, the first prototype BV 155B completed just a few flights before colliding with the ground. Of course, the second prototype was taken.

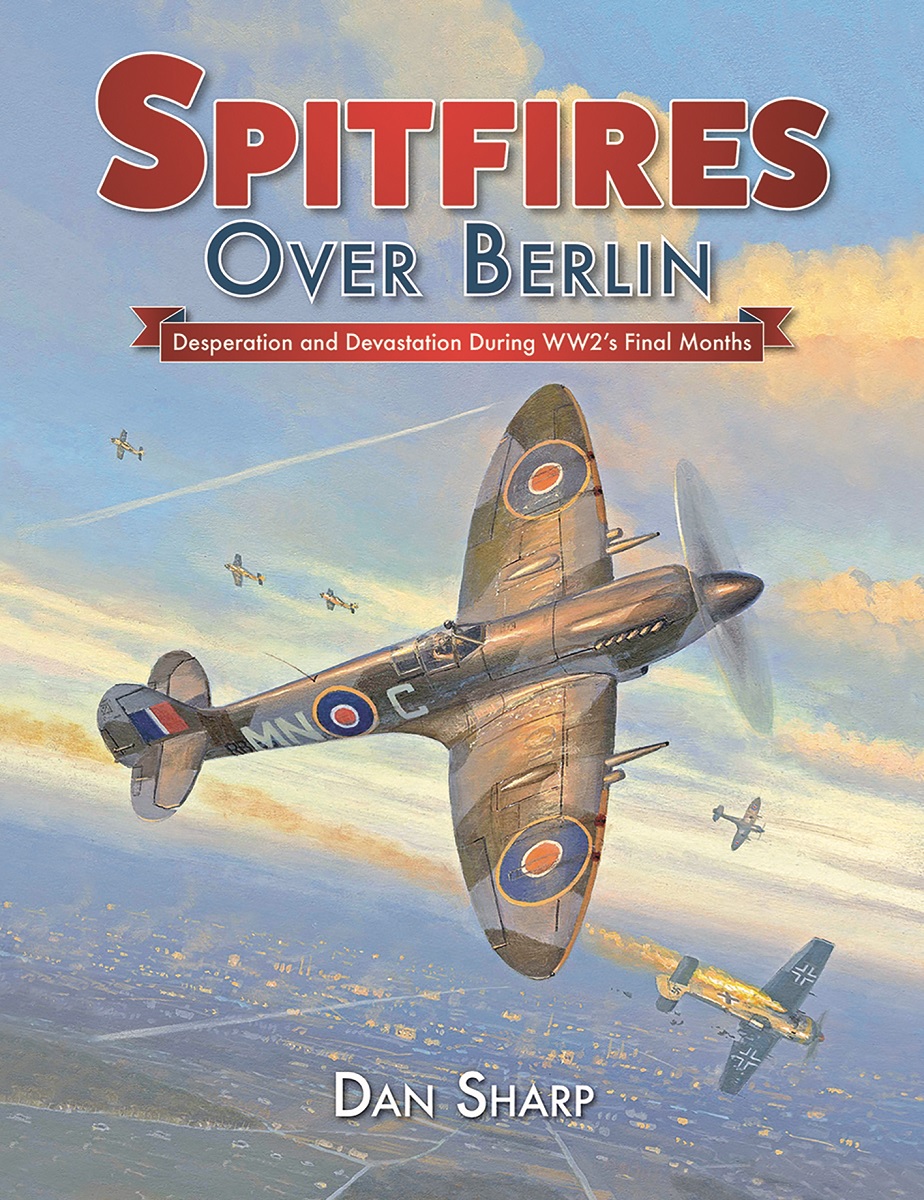

There is no getting around the fact that those dreaded high-altitude American bombers never materialized in the skies over Germany. It was an extraordinary feat for the small and under-resourced Blohm & Voss team to develop and build a new and complicated fighter in around 18 months. However, if it had been put into production more quickly, the BV 155 might have proven valuable in battling the most modern, high-flying Allied reconnaissance aircraft.

With a ceiling of just over 15 km, the Griffon-engined Spitfire PR Mk.XIX was virtually untouchable from the time it reached active units in May 1944 until the conclusion of the war. The unarmed PR Mk.XIX would have been extremely vulnerable with BV 155Cs in use by the Luftwaffe.

Blohm & Voss BV 155 is published by Mortons Books and is available to order here along with many other beautiful aviation books.

Photo by GoodFon.com and Reddit