“I fired at the bandit until it ballooned to 3 times in intensity then suddenly disappeared from my radar scope at approximately 1,200 yards, 6:30 low. I expended 800 rounds in 3 bursts,” Airman 1st Class Albert Moore, B-52D Diamond Lil tail gunner

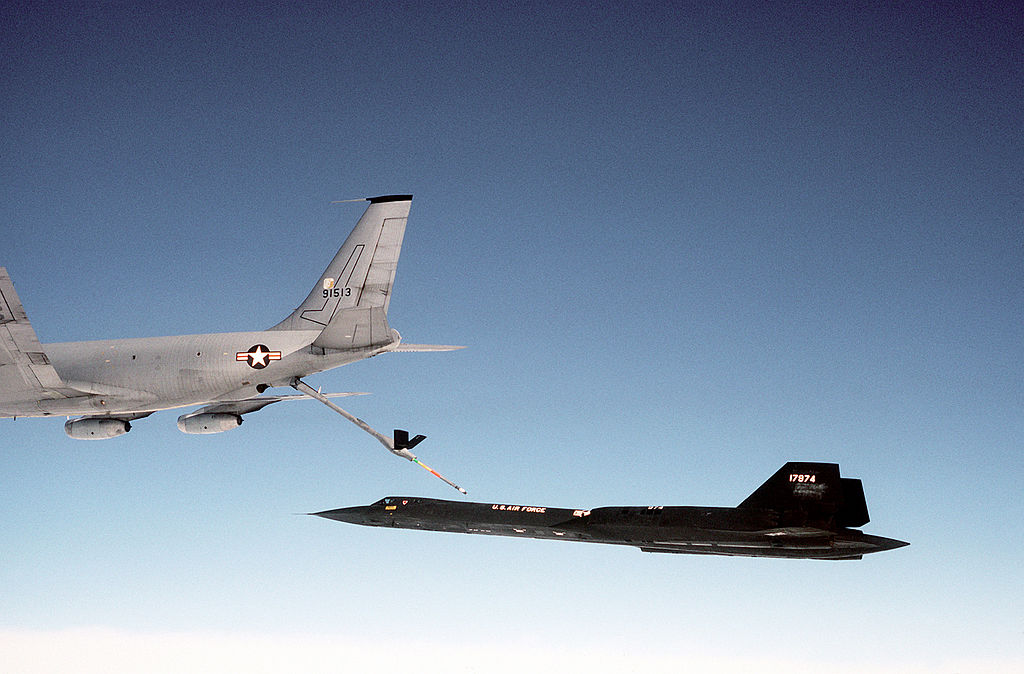

The B-52 Stratofortress close to the north gate would have a great Christmas Eve tale to tell if the landmarks at the U.S. Air Force Academy could speak.

That day in 1972, the crew of the B-52D, tail number 55-083, took off from Utapao Royal Thai Naval Airfield, as explained in the article Records detail MiG kill by ‘Diamond Lil’ tail gunner. Their mission was to bomb the North Vietnamese railroad yards at Thai Nguyen as part of Operation Linebacker II, which took place Dec. 18–29, 1972.

However, unlike present-day bombing missions, Diamond Lil’s crew faced enemy airpower. A North Vietnamese MiG-21 raced to intercept the B-52, callsign Ruby 3, and her crew. The Buff’s tail gunner, Airman 1st Class Albert Moore, noticed the MiG’s approach.

“I observed a target in my radar scope 8:30 o’clock, low at 8 miles,” he wrote six days later in his statement of claim for enemy aircraft destroyed. “I immediately notified the crew, and the bogie started closing rapidly. It stabilized at 4,000 yards at 6:30 o’clock. I called the pilot for evasive action and the EWO (electronic warfare officer) for chaff and flares.

“When the target got to 2,000 yards, I notified the crew that I was firing. I fired at the bandit until it ballooned to 3 times in intensity, then suddenly disappeared from my radar scope at approximately 1,200 yards, 6:30 low. I expended 800 rounds in 3 bursts.”

Tech. Sgt. Clarence Chute, another gunner, verified the kill in his report.

“I went visual and saw the bandit on fire and falling away,” wrote Sergeant Chute, who was a gunner in Ruby 2. “Several pieces of the aircraft exploded, and the fire-ball disappeared in the undercast at my 6:30 position.”

The kill of Airman Moore is the last confirmed kill by a tail gunner employing machine guns in wartime, and one of only two confirmed kills by a B-52D during the Vietnam War.

Following the MiG kill, Airman Moore said, “On the way home, I wasn’t sure whether I should be happy or sad. You know, there was a guy in that MIG. I’m sure he would have wanted to fly home too. But it was a case of him or my crew. I’m glad it turned out the way it did. Yes, I’d go again. Do I want another MIG? No, but given the same set of circumstances, yes, I’d go for another one.” Moore died in 2009 at age 55.

Linebacker II brought the North Vietnamese government back to the negotiating table after earlier talks had broken down. A month after the campaign, North Vietnam and the United States signed a ceasefire agreement.

Diamond Lil kept on flying even after the Vietnam War had ended. Overall, it logged more than 15,000 flight hours and participated in over 200 combat missions between its commissioning in 1957 and its decommissioning in 1983. It came to the Academy shortly after it was decommissioned.

Photo by U.S. Air Force photo/Staff Sgt. Don Branum