The SR-71 Blackbird

The Lockheed A-12 and YF-12A aircraft were the basis for developing the SR-71, also called the “Blackbird” or long-range, advanced strategic reconnaissance aircraft. The 4200th (later 9th) Strategic Reconnaissance Wing at Beale Air Force Base, California, received the first SR-71 to begin service in January 1966. The first SR-71 flight occurred on December 22, 1964. On January 26, 1990, the US Air Force retired its entire fleet of SR-71s.

For almost 24 years, the SR-71 held the record for being the fastest and highest-flying operational aircraft in the world. It could cover 100,000 square miles of the Earth’s surface per hour from 80,000 feet. Two world records for its class were set on July 28, 1976, by an SR-71: an absolute speed record of 2,193.167 mph and an absolute altitude record of 85,068.997 feet.

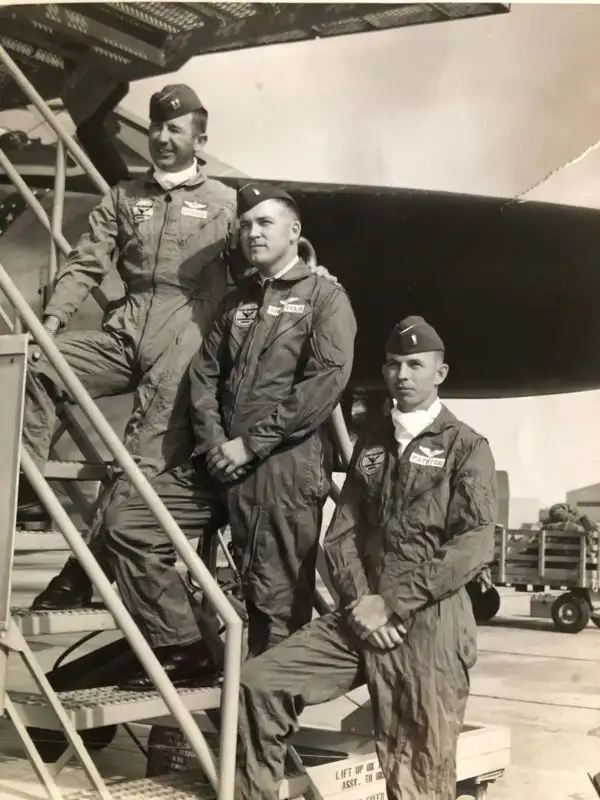

The fifth SR-71 crewmember to reach the 900-flying hour plateau

Six of the nine years that Colonel (Ret) James H. Shelton Jr. spent at Beale Air Force Base (AFB) passed by piloting the SR-71. He was the fifth member of the SR-71 crew to achieve the 900 flight hour plateau. Though few Habus have reached that milestone, most commercial airline pilots would consider that a paltry amount of flying time.

According to Richard H. Graham’s book SR-71 Blackbird Stories, Tales and Legends, Shelton recalls a special operational Blackbird mission that took place during his initial overseas deployment to Kadena AB in May 1969 with Major Tom Schmittou (RSO):

“The operational tasking from SAC headquarters always had maintenance personnel generating a primary and secondary aircraft. On 13 June 1969, we were in primary aircraft #979 for an operational mission over North Vietnam. It was a typical four-hour flight, consisting of a single east-to-west pass across Hanoi, air refuel over Thailand, then a west-to-east pass just south of Hanoi, returning to Kadena AB.

“The engine start, takeoff, air refueling, and acceleration to Mach 2.8 at an altitude of 77,000 feet went as planned. At the navigation checkpoint, Tom informed me that the navigation system was drifting and the mission should be aborted. Tom made the abort call, and I turned the aircraft back to Okinawa. The descent from altitude and approach for landing was normal. Moderate rain was falling, so I applied the rain remover fluid to the front windscreen, allowing me to see the runway about 2 to 3 miles out.

Cockpit fogging and drag chute deploying

“The touchdown on the runway went smoothly. However, as I retarded the throttles to idle, the cockpit began to fill up with fog (water vapor). I had forgotten to increase the cockpit temperature to 85 degrees or higher, to prevent the formation of cockpit fogging; I remembered one pilot had previously blown the canopy off on landing just to see the runway and I really didn’t want to do that! I quickly flipped the cockpit temperature switch from automatic to manual hot. This eliminated the fog in the cockpit, but did nothing to slow the aircraft down. Being so engrossed with holding the temperature switch in the full hot position (spring-loaded), thereby fixing one problem, I inadvertently created another: I forgot to deploy the drag ‘chute.

“The drag ‘chute must be deployed to slow the aircraft on landing, especially on a wet runway. In my mind, and in actuality, the aircraft was slowing enough. I applied the brakes and the antiskid started cycling like crazy, so I turned it off, but to no avail. I then shut down one engine as I saw the end of the runway coming up very, very quickly (at about 120 miles hour). Fortunately, the runway at Kadena had a cable barrier installed about 1,000 feet from the end, specifically for the SR-71.”

As Graham explains “the BAK 11/12 barrier was installed at two of our operating locations – on runway 16 at Beale and on runway 05R on Kadena. The barrier was designed to stop the plane at a maximum speed of 180 knots. Arming and disarming the barrier was controlled in the tower. At both Kadena and RAF Mildenhall, we had a crewmember in the tower during all takeoffs and landings to make sure everything went smoothly.

Only two successful SR-71 Blackbird Barrier Engagements

“When armed, the barrier was activated by the aircraft nosewheel and main gear as they rolled over pressure-sensitive switchmats located in the runway before the arresting cable. The switches energized a timing computer that caused the arresting cable to be thrown up to engage the main gear struts. On engagement, the arresting cable was pulled out with a relatively constant restraining force to stop the aircraft within 2,000 feet. This was all theoretical. In actual practice, the number of unsuccessful SR-71 engagements far outnumbered the successful ones. Besides Jim successful engagement, I know of only one other.”

Shelton continues. “The barrier is designed to pop up in front of the two main landing gear and stop the aircraft in 400 to 500 feet. The barrier unit uses the B-52 aircraft brake system to slow the aircraft and bring it to a stop (hopefully!). Boy, was I relieved that the barrier worked as advertised! There was one unsuccessful barrier engagement on 10 October 1968 at Beale, where the SR-71 (#977) was destroyed. There were only two barrier engagements recorded at the time, and fortunately, ours was the successful one.

Allowed to continue flying after one of only two successful SR-71 Barrier Engagements

“Well, I just knew my SR-71 flying days were over as I climbed out of the aircraft. This incident terminated my flying at Kadena AB for this tour. The maintenance personnel worked the rest of the day and all through the night replacing the gear doors, hydraulic lines, and electrical wires on the main landing gear damaged by the barrier cable. I owe a big thanks to those maintenance personnel, because the aircraft was ready to fly the next day. They sure saved my six o’clock position (butt).

“Since this was the second fogging incident, Lockheed designed a lever that the RSO moved to stop air from entering the cockpit before landing, eliminating any chance of fogging the cockpit as the throttles were retarded. I call that handle the “Shelton lever.” Needless to say, I was allowed to continue flying, thanks to the thorough flying evaluation the standardization crews administered to me on my return to Beale AFB.”

Photo by U.S. Air Force