Variously referred to by American media as “The Stab in the Back-yard”, “The Fishbed Flap” “The Redhawk Incident” or more ominously “The Canuck Invasion Crisis”, the Redhawk Program brought Canadian-American relations to the breaking point.

The following story originally appeared on the Vintage Wings of Canada website.

October 31st, 2002, right-wing blabbermouth and two-time Republican presidential nominee hopeful, Pat Buchanan misguided by a knee-jerk notion that Canada was a cesspool of anti-American “sentiment” referred to our country as Soviet Canuckistan. Half the country was quietly infuriated as Canadians are wont to be, while the other half was amused in an elitist sort of way. From that point on, the snarky sobriquet has been attributed to Buchanan by nearly all news agencies, but he in fact was not its originator.

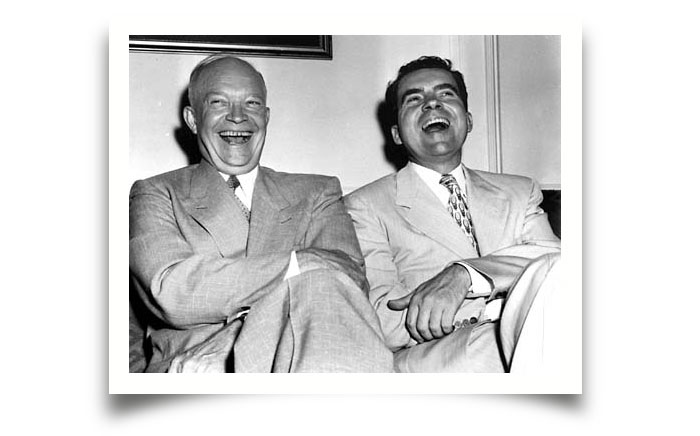

Buchanan was in fact quoting his old boss – Richard Nixon, for whom he was a senior political advisor during his years as president. However, it was not President Nixon who was so angry with Canada, but rather Vice President Nixon back in 1960 at the height of the Cold War, and though Canadians were incensed then, I have to admit… he had a point. Buchanan would remember the nasty spell of hemispherical winter that fell upon Canadian-American relations at the beginning of that decade for he was a Journalism student at Columbia University at the time. In fact, he would be so outraged by the incident that, in 1962, he would write his Masters’ thesis on the expanding trade between Canada and Cuba.

The political maelstrom that set Canada against America back in 1960 lasted not much more than one year but it took nearly a decade for heads to cool off and for relations to return to normal. Variously referred to by American media as “The Stab in the Back-yard”, “The Fishbed Flap” “The Redhawk Incident” or more ominously “The Canuck Invasion Crisis”, the events of that year brought Canadian-American relations to the breaking point. There were members of Congress in Washington who were ready to sanction Canada and there were commanders of the United States Air Force who were ready to go toe to toe with the RCAF. The commander of the Strategic Air Command, General Curtis Lemay took it even further when he offered “My solution to the problem would be to tell those frozen Canucknbastards frankly that they’ve got to draw in their horns and stop their aggression or we’re going to bomb them into the stone age.”

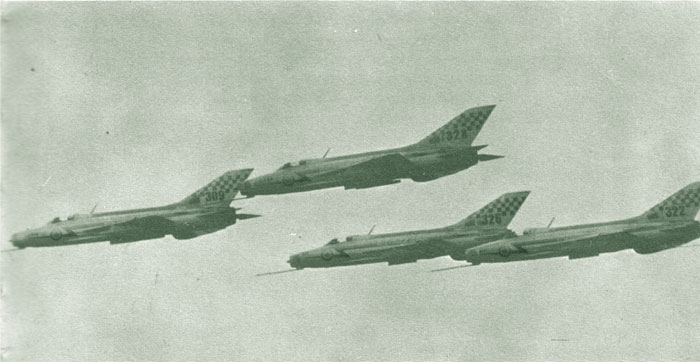

In the early Fall of 1960, like a ferocious Arctic front, news that the Royal Canadian Air Force had made a secret purchase of 30 state-of-the-Soviet-art MiG-21 fighters to replace what would have been a deployment of the production model Avro Arrow interceptor swept across America. Americans from coast to coast were stunned and feared that Communist influence had spread to their northern border was rampant. Across America, anti-Canadian rhetoric was boiling over and people began to cut down maple trees in protest from Maine to Wisconsin. In one act of retaliation, three beavers were executed by pistol on the lawn outside the State Legislature in Frankfurt, Kentucky.

Most Americans and indeed many Canadians wondered what possibly could have motivated the Government of Canada and the Royal Canadian Air Force to so obviously challenge the here-to-for sleeping giant that was the United States of America. To understand the complexities and emotions surrounding the purchase (which became known as the Redhawk Program we have to go back to 1953 and the beginnings of a national dream called the Avro Arrow.

The Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow was a delta-winged interceptor aircraft, designed and built by AvronAircraft Limited (Canada) in Malton, Ontario, Canada, as the culmination of a design study that began in 1953. It was bold, elegant, gorgeous in a post-war sort of way and oh-so-Canadian. Considered to be both an advanced technical and aerodynamic achievement for the Canadian aviation industry, the CF-105 held the promise of Mach 2 speeds at altitudes exceeding 50,000 ft (15,000 m), and was intended to serve as the Royal Canadian Air Force’s primary interceptor in the 1960s and beyond.

Not long after the 1958 start of its flight test program, the development of the Arrow (including its Orenda Iroquois jet engines) was abruptly and controversially halted before the project review had taken place, sparking a long and bitter political debate that still simmers today in web forums and dark chat rooms.

The controversy engendered by the cancellation and subsequent vandalistic destruction of the aircraft in production, remains antopic for debate among historians, political observers, industry pundits and maple-flavoured crackpots. This action effectively put Avro out of business in a heartbeat and scattered its highly skilled engineering and production personnel across engineeringdom. The incident was a traumatic one… and to this day, many mourn, nay weep for the loss of the Arrow.

Though surely the Avro employees and support workers suffered the greatest catastrophic implosion of their dreams and most alacritous evaporation of their livelihoods, the pain of failure and urge to strike-out at someone responsible impacted the officers and senior bureaucrats at the Department of National Defence’s Directorate of Systems Procurement in Ottawa with equal force. It was here, on the creaking wooden floors of DND’s Hunter Building on O’Connor Street that the idea of an all Canadian, all-weather, long-range fighter interceptor was put forward. The men who worked on the fourth floor directorate became known as the “Hunter Boys” – to a man were air force veterans of the Second World War – pilots, navigators, intelligence men.

The “Hunter Boys” looked upon the Arrow program as parents would look upon a child – albeit an overweight, underperforming child who spent his inheritance like King Farouk on a bender. When the program was canceled, it was to the “Hunter Boys” like the death of baby Charles was to the Lindberghs – devastating, final and buried before they knew what hit them. Like the Lindbergh Baby case, culprits were sought to hang the blame on. Some believed it was Prime Minister Diefenbaker’s personal decision,na few in the inner circle believed that then Minister of National Defence, George Pearkes, was being blackmailed by an East German Mata Hari and cabinet courtesan by the name of Gerda Munsinger (this would be proven completely wrong in Munsinger’s later autobiography “My Life Under the Tories”), but the “Hunter Boys” had their own culprit – the American military industrial complex (as it would become to be known after Eisenhower’s farewell speech).

The Americans were not fearful of the Arrow’s promised abilities (in fact they laughed at a reporter’s suggestion they might consider buying Canadian) for they had aircraft of equal or better performance. What the Americas wanted was not Canadian technology, but the Canadian market for military aircraft. Canada had at the time one of the largest air forces in thenworld with scores of large bases from Newfoundland to Vancouver Island and hundreds of fighter aircraft and hundreds more utility and transport aircraft. If Canada took to building its own airplanes to replace the aging Sabres and then got it into its thick northern head to build aircraft of all types, billions of 1950s dollars would go into the Canadian economy and not the one south of the border.

It was their certainty that the promise of the Arrow was slain by corporate decree and that the defiling of her beautiful white corpse can been carried out at the insistence of malevolent corporate and political captains in Washington, that led the “Hunter Boys” to seek a form of revenge so daring, so complete that it would touch every American. They would set in motion a plan to purchase replacement fighters, not from the United States, not from Western Europe, but from the Eastern Bloc. Led by the aptly named Air Commodore Frederick Roe, DFC, the “Hunter Boys” met secretly in late March in the darkened tap room of the Bytown Inn just across O’Connor Street from the Hunter Building. These meetings came to be known as the “Labatts Conspiracy.”

In a matter of a couple of weeks, they had set in motion a plan to engage key members of the Soviet regime. Low-, mid- and high level talks and meetings were sought with RCAF brass and then Soviet leaders and by June of 1959, the procurement team had made entreaties to diplomats and party officials at the Embassy of the Soviet Union in Ottawa’s Sandy Hill.

In late August of 1959, a large team of Canadian officials including A/C Roe, top RCAF brass, test pilots, aeronautical engineering experts from the Paul Kissmann Institute flew by RCAF Northstar to West Berlin. From here they were secreted through checkpoints and to the East German Air Force base at Holzdorf in Schleswig-Holstein. There, they were given unprecedented access to the heretofore secret MiG-21F (NATO codeword Fishbed-B) with a full demonstration by an up and coming Soviet test pilot by the name of Yuri Gagarin. Though the progenitor of the Fishbed-B, the Ye-4 (for Yedinitsa – a Russian word meaning “One-off” or single prototype) had made its first public appearance during the Soviet Aviation Day display at Moscow’s Tushino airfield in July 1956, little if anything was known about the type. The Canadians were concerned about the MiG’s short range but were very impressed with its Mach-2 top end, and it acceleration to the mach. Interpreters for the delegation translated Gagarin’s grinning comment after the show as “MiG-21 is lightning bolt across Mother Russia. MiG-21 runs like a scalded dog on Nevsky Prospekt.”

The flying display led in turn to the highest level talks yet – between First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union, Anastas Mikoyan (no less than brother of the Artem Mikoyan, one of the USSR’s greatest aircraft designers) and Prime Minister John George Diefenbaker of Canada. Though the meetings were secret in every way, it was deemed a good idea to hold them in plain sight and so the high level meeting took place on the main floor of the New technologies, New World Showcase – a trade fair held that November in West Berlin. Though Diefenbaker lacked the natural charm and ease of Mikoyan, both men were born in farming country far from their nations’ capitals and they connected on a personal level. That day, at the Soviet Union’s vast Gallery of Progress and Household Joys, amidst the 400lb 9″ colour TVs, steam powered lawn mowers, atomic ovens and toasters the size of tombstones, a deal was struck.

Canada would receive 30 brand spanking new, state-of-the-Soviet-art, all-weather MiG-21 interceptors straight off the assembly line as well as spares, technical assistance and training, tools, jigs, support equipment and a whole lot of secrecy. It was the largest Soviet-Canadian weapons deal since the Lend-Lease program sent Canadian-built Hawker Hurricane XIIs to Russia in the 1940s. It has never been clear what the Soviets were to receive in payment, but in 2012, the “top secret” status of the files will be removed and the figures will no doubt be made public. It was rumoured at the time, that the Soviets were pushing for bases in Yukon and Labrador, but these were never granted. The Canadians needed aircraft and revenge, but not Soviet allies. 441 Squadron was selected for the Redhawk Program for the high quality and experience of its pilots.

And so, like the inevitable conflict that follows an arms race, the agreement ratified that day set in motion a series of steps that would strain Canadian-American relations for decades. The speed at which all this happened was fueled on Canada’s end by Air Commodore Roe’s revenge-lust and on the Soviet side by unbridled and unfounded glee at the prospect of extending their influence to the 49th parallel. The Reds had somehow convinced themselves that the Canadians were turning socialist – bolstered by their willingness to shop the Soviet weapons market and the fact that Canada was in the throws of socializing their entire national health care system. They embraced this delusion like a crackhead leaps for joy at a police bait car. How wrong they were!

Over the next three months, 30 shiny new MiGs were selected from the line at the Mikoyan OKB plant outside Moscow, disassembled, crated and shipped by rail car to the White Sea port of Severodvinsk. Throughout the months of February and March of 1960, a series of rusty Russian freighters were loaded with anywhere from one to 6 crated aircraft under the cover of darkness (not a hard thing to achieve at that latitude in February). One by one, the weighed anchor, and shaped a course north and then west over the top of Scandanavia and out to the open sea, bound for the east coast of Canada and the Bay of Chaleur. Each ship was secretly shadowed by a Russian submarine all the way.

Off-loading by night at the port of Bathurst, New Brunswick, each ship disgorged its crated mysteries onto CNR flatcars under the supervision of Air Force MPs. The shrouded cars were then coupled with a locomotive and sent on a two hour overland journey south to RCAF Station Chatham – the base for the fighter OTU for Canadian Sabres. Here under airtight security, Mikoyan technical representatives supervised the re-assembly of the fighters as they arrived, and a team of four pilots from the Luftstreitkrafte der NVA (East German Air Force) carried out night-time flight training with pilots of 441 Squadron who had come home from Marville, France where they had been stationed. Most Anglo and Franco pilots had been dispersed to other units and the roster was filled out by Canadians of Slavic, Balkan and even Greek ancestry. This was done because the hastily purchased MiGs had instruments that were calibrated in metric units and displayed in the Cyrillic alphabet. It was thought that those who had grown up around this alphabet would have an easier time adapting.

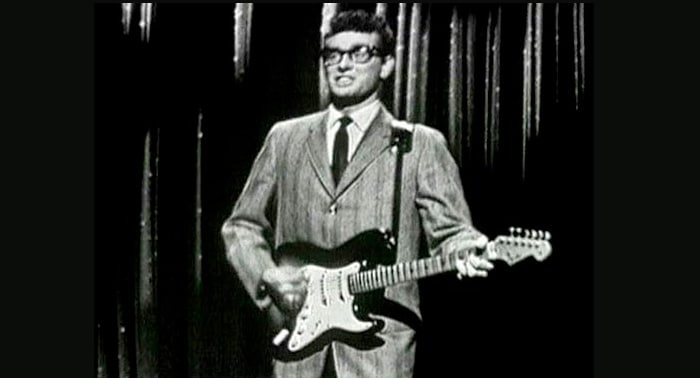

Over the next two to three months, flight training proceeded apace and by late June 1960, crews were ready for a ferry flight to their eventual home base of Cold Lake, Alberta. But first they had to pick a name for their new fighter aircraft, which the RCAF was calling the CF-121. At this time, the RCAF aerobatic demonstration team, the Golden Hawks were stationed at the other side of the base. The Squadron Commander, S/L Stefan Swillka, inspired by the Hawks, named the new type the Redhawk. More creative squadron pilots nicknamed it the “Stratocaster” or “Strat”, a name that paralleled their German instructors who called it the “Balalaika”.

Before dawn on June 23rd 1960, 9 pairs of CF-121 Redhawk fighters spooled up on the flightline at RCAF Station Chatham. (8 fighters would remain in storage for until needed and the last two had not yet arrived by sea). Though ramp lights were kept off for secrecy, ground crew could see for the first time the freshly applied 441 Silver Fox Squadron checkerboard tail markings, aircraft numerals, RCAF titles and roundels. Great rivers of superheated exhaust billowing from their shrieking Tumanskii turbojets turned the mid-summer pre-dawn ramp into a noisy inferno. Led by S/L Swillka, each gleaming fighter lurched forward in turn, wheeled left, and taxied in line to the end of runway 25. There, in pairs, Red Fox 1, Red Fox 2, Red Fox 3 and the rest pushed the throttles past the detents, lit the burners and thundered down the runway to lift off into history. They would transit from Chatham direct to RCAF Station St. Hubert near Montreal. Unable and unwilling to fly over or even near Maine, the ferry flight would sorely test even the ferry range of the heavy, gas-sucking fighter. Their course would take them north to Trois Pistoles on the south shore then southwest following the mighty Fleuve St. Laurent south of its shoreline. Radio silence was to be kept the entire way.