The Doolittle Raid forced the Japanese to recall combat forces for home defense even though it only caused small damage, and it made Japanese citizens nervous

U.S. morale dropped in the spring of 1942 as a result of the frequent Japanese victories. A triumph was absolutely necessary for the nation.

According to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force article, America Hits Back: The Doolittle Tokyo Raiders, Capt. Francis S. Low, a U.S. Navy submarine, came up with the plan to use medium bombers from the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) flying from a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier to launch an attack against the center of Japan.

Gen. Henry “Hap” Arnold gave Lt. Col. James Doolittle, an accomplished pilot, and charismatic leader, the challenging assignment of preparing for and leading the attack (known as Special Aviation Project No. 1).

Doolittle joined the Army in 1917, became a flying cadet, and got his commission in 1918, according to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force article Doolittle Raid. He was the recipient of the coveted Schneider, Bendix, and Thompson aviation awards in the late 1920s and early 1930s. In 1929, Doolittle created aviation history when he completed the first blind flight, relying on the aircraft’s instruments for takeoff, flying, and landing.

In 1940, as war seemed inevitable, he returned to active duty after leaving the Army Air Corps in 1930.

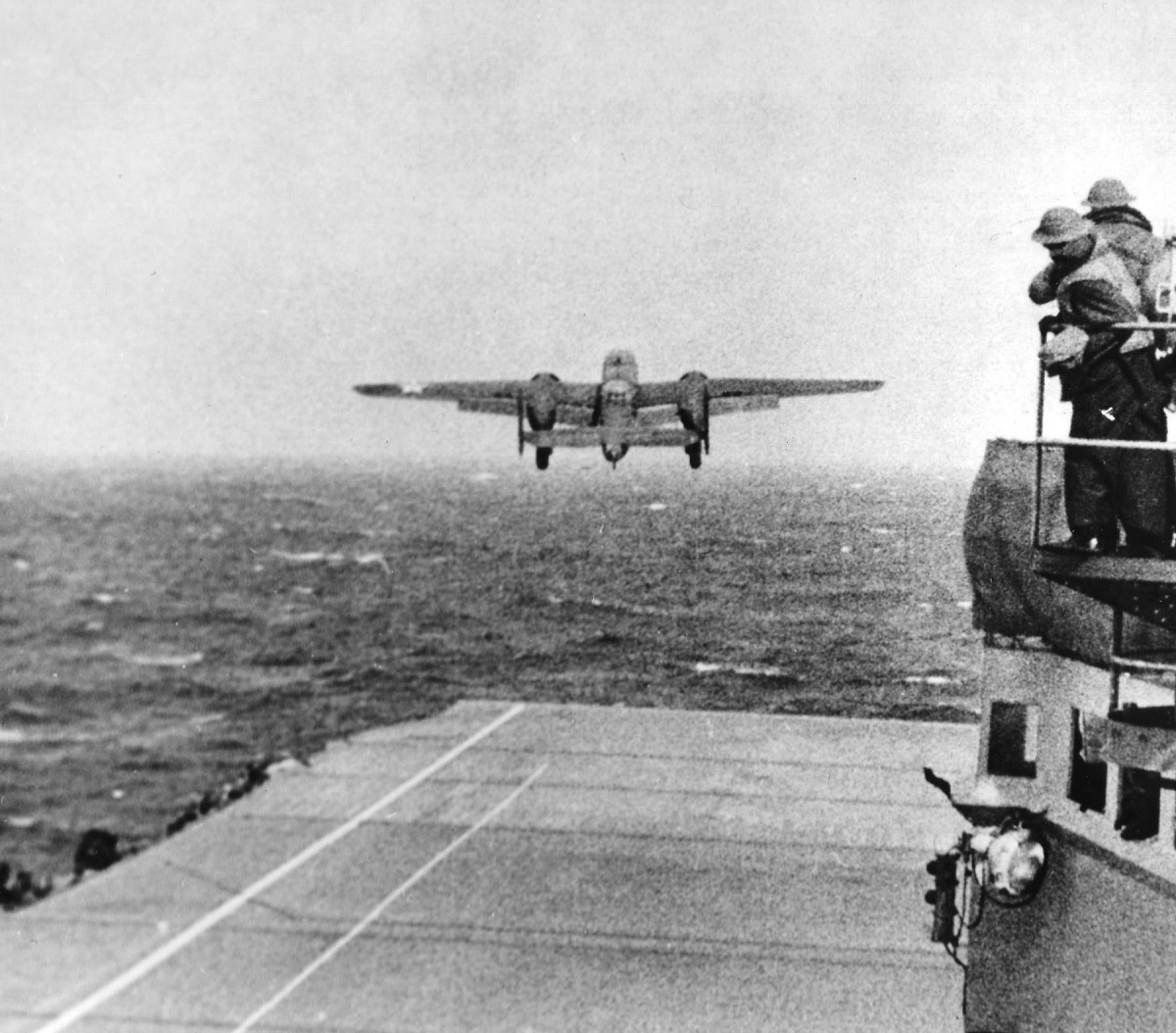

The USAAF selected the B-25 Mitchell medium bomber for the task because it was the only available aircraft with the necessary range, bomb capacity, and short takeoff capability. The 17th Bombardment Group, Pendleton Field, Oregon, provided the B-25B aircraft and 24 crews of qualified volunteers.

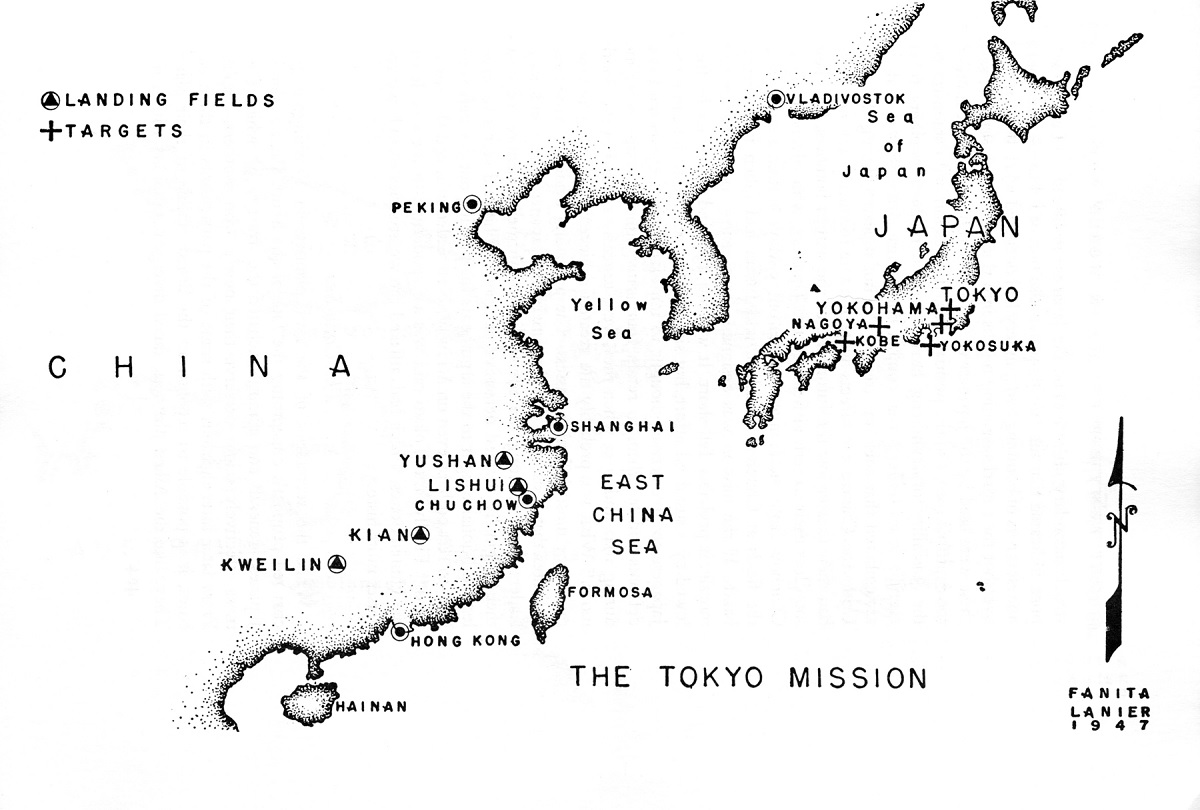

The B-25s had to depart Japan at a distance of roughly 450 miles, bomb chosen targets in cities like Yokohama and Tokyo, and then fly 1,600 miles to friendly airfields in mainland China. The mission was dangerous since medium bombers had never flown from a carrier and the American Navy task force was in danger by entering enemy territory so far.

The aircrew chosen for the operation underwent training at Eglin Field, Florida, under the direction of Lt. Henry L. Miller, a Navy pilot from Pensacola Naval Station, who assisted them in learning how to take off within 300 feet, the maximum distance allowed on the carrier USS Hornet. In addition, the aircrew worked on cross-country and night flying, radio-free navigation, low-level bombing, and aerial gunnery.

Noteworthy because the Norden bombsight was ineffective at low altitudes, the pilot and armament officer for Doolittle’s group Capt. C. Ross Greening developed a replacement device, which is connected to the cockpit through the pilot direction indicator, allowed the bombardier to give the pilot aircraft turn directions without relying on voice communication.

Actually, these bombsights were produced by Eglin Field’s metalworking shops with $20 worth of supplies!

The crews finished their training by the middle of March and took a flight to San Francisco to board their 16 B-25 bombers on the recently constructed aircraft carrier USS Hornet.

Marc A. Mitscher, the commander of the Hornet, sailed for the covert mission on April 2, 1942, in broad daylight rather than at night because of an inexperienced crew.

The task force, under the leadership of Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, was about 650 miles from Japan when it came upon an enemy patrol boat at dawn on April 18, 1942.

Nobody was aware of whether it had radioed Japan a warning before being sunk.

Col. Doolittle and Admiral Halsey were faced with a difficult decision: postpone the raid or launch as scheduled and run the danger of running out of fuel. All 16 of Doolittle’s aircraft took off after he decided to launch an attack. When the Raiders arrived in Japan, they dropped their bombs on industrial centers, military bases, and storage areas for oil before departing over the East China Sea.

The Raiders were unable to reach their planned airfields as their fuel gauges began to decline. They all eventually crashed into China, bailed out, or dumped themselves in the water (one crew diverted to the Soviet Union). The Chinese people’s assistance allowed the majority of the Doolittle Raiders to successfully reach friendly forces (Japanese forces later executed as many as a quarter-million Chinese citizens in retaliation for this assistance).

After Japan’s numerous early wins, American morale plummeted, but when news of the attack emerged, it quickly recovered. Furthermore, even if the Doolittle Raid only did minimal damage, it made the Japanese call up their combat troops for home defense and instilled dread in the hearts and minds of the populace.

Admiral Yamamoto also gave the order for the disastrous attack on Midway Island, which was the tipping point in the Pacific War, in order to stop any further American airstrikes on the homeland.

How this illustrious operation was carried out is explained in the video that follows.

Photo by U.S. Air Force

Source: National Museum of the U.S. Air Force