The Germans’ closest option for precision bombers was the Ju-87 Stuka, and they employed them as such until the Battle of Britain

The Stuka, also known as the Junkers Ju 87 or Sturzkampfflugzeug (German for “dive bomber”), was a ground-attack and dive bomber aircraft. Designed by Hermann Pohlmann, it first flew in 1935. The Ju 87 served the Axis forces during World War II and made its combat debut in 1937 with the Luftwaffe’s Condor Legion during the Spanish Civil War.

‘The Ju-87 Stukas were the nearest thing to precision bombers the Germans had, and they were used as such right up until the Battle of Britain,’ points out Francis Dickinson, Analyst at National Health Service (NHS), on Quora. ‘However, the Battle of Britain made their shortcomings very clear even if the Germans were able to badly damage three Chain Home stations with them as well as some other things.

‘The Stuka was not the fastest plane in the sky, but its crippling weakness was the very dive bombing that gave it its precision bombing approach. To divebomb you continue in a straight line at a constant speed, diving toward the target. This means that when you start the bombing run you are signaling what you are going to be doing for the next few seconds. This means that the fighters trying to shoot you down know not only where you are but where you are going to be. You also lose a lot of altitudes so it’s hard for the fighters to protect you at – and because dive bombing was at a constant speed and other planes dived to gain speed most planes can trade their altitude for speed to catch the dive bomber. Further, if you had an escort of fighters at the start of the dive-bombing run either they didn’t join you in the dive at all (in which case they weren’t with you at the end) or they did and gained a lot of speed in the dive (in which case they weren’t with you at the end). This made it a very easy target whenever it tried to bomb something and there were fighters around and even opportunist fighters could catch Stukas when they were effectively unprotected.’

Dickinson continues;

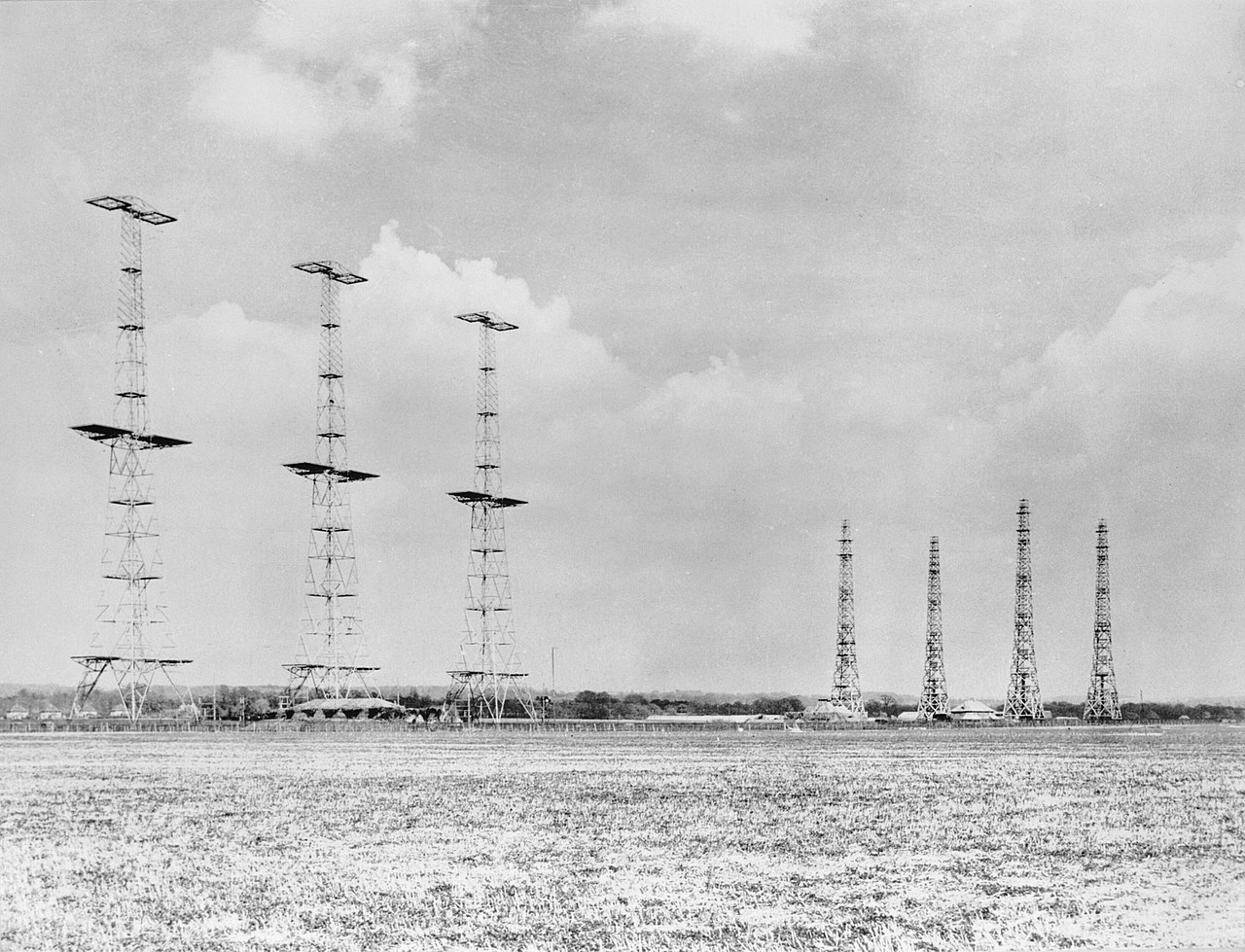

‘Then there’s the matter of taking out the radar stations by bombing. It was possible to knock over the wooden huts they used, but that didn’t do very much that couldn’t be repaired or replaced in only a few hours. And as for the towers such as the ones seen below the open girder construction means that short of the kinetic damage from a direct hit on one of the towers not much damage would be done by bombs; neither blasts nor flying metal would do very much. Three stations were badly damaged by bombing from Stukas, but that was nowhere near enough to break the chain and on the one occasion I know of the chain was actually broken the Germans weren’t aware of it.

‘Also, the Germans simply didn’t get how important the British radar system was. They had radar of their own that could sweep an area to look for things that were the equal of the British radar – but what they didn’t have was anything remotely approaching the Dowding system to integrate reports from the radar and on the ground observers into something the fighters could actually use, working out which cases were the observers and different radar systems tracking the same planes, plotting the planes on a map, and then sending where their targets and threats were to the pilots. Below is the most famous actual room used, complete with the maps and markers with sticks to move them to track the German planes. Without that the radar was an early warning system rather than part of a command and control network.

‘As for defending the Stukas with German fighters, they were. But the British had radar so they could ensure that the Germans were outnumbered in most engagements because they knew where and when the Germans were coming. The Spitfires would go in first – and the German fighters had to fight the Spitfires or be shot up while in formation. Then the less capable Hurricanes would go in on the bombers, putting holes in many and shooting some down. And because the British always knew where the German planes were coming, they could always have some opportunist observers (that the Germans thought were patrols) watching for if the fighters were drawn off; escorts couldn’t go after patrols because it would uncover their bombers.’

Dickinson concludes;

‘The Stukas were withdrawn from the Battle of Britain when between August 8 and 18 1940 Germany lost 20% of its Stukas to the RAF. Those were clearly unsustainable losses – and the Germans had a fight coming up against an enemy that was known to not have one of the strongest air forces in the world; the Stukas were needed for the Russia campaigns where they wouldn’t be quite such easy targets. The lesson was learned – dive bombing was a great tactic against enemies who didn’t have a first-rate air force but they were very hard to provide cover for and fighters could shoot them down pretty easily if the Germans didn’t control the skies.’

Photo by Bundesarchiv, Bild via Wikipedia and Crown Copyright