“I assumed the Soviet MiG-31 fighter pilot would like nothing better than an opportunity to fire his missiles at an SR-71 Blackbird. Certainly, the SR-71 Blackbird would be a prized target,” Ed Yeilding, former SR-71 pilot

Major Mikhail Myagkiy, a retired Soviet MiG-31 pilot, participated in several attempts to intercept SR-71 Blackbirds during Peacetime Aerial Reconnaissance Operations Program (PAROP) missions to the Barents Sea area.

According to his logbook, Myagkiy has conducted 14 successful SR-71 intercepts:

21 August 1984

14 March 1985

18 March 1985

15 April 1985

17 July 1985

19 December 1985

20 January 1986

31 January 1986

21 February 1986

28 February 1986

1 April 1986

6 October 1986

23 December 1986

8 January 1987

Two of these intercepts were carried out by Ed Yeilding aboard an SR-71. Yeilding discusses the intercept from October 6, 1986, in Lockheed Blackbird: Beyond the Secret Missions (Revised Edition), written by Paul F. Crickmore.

As Yeilding recalls one of his “Barents missions was especially memorable because we had an encounter with a Soviet MiG-31. Because most details of Blackbird flights were classified at that time, I made no notes about the encounter, so I cannot verify the date of the encounter. I am certain that RSO Curt Osterheld was with me at the time. Curt and I had only two tours together at Mildenhall, so the encounter was between 25 Aug 1986 and 8 Oct 1986, or between 14 Apr 1987 and 7 May 1987. (I don’t remember why that second tour was only three weeks.) I think the encounter might have been the last flight of our first tour. My flight records show we had a 4.1-hour mission with Blackbird tail ‘980 on 6 Oct 1986.

“On that memorable MiG-31 encounter mission, I was glad to be flying with Curt, an outstanding RSO admired by all, and, by the way, one of the most popular Habus. There we were, 71,000ft, starting our Mach 3.0 reconnaissance track, heading east just outside the territorial waters of Russia’s Murmansk area coastline. I knew Curt was very busy in the rear cockpit with his many duties monitoring and managing cameras, sensors, and navigation. I kept a constant crosscheck of the many indicators and controls in the front cockpit, watching carefully for potential system failures, and maintaining stable airspeed and the most efficient altitude for our weight.

“After Curt and I completed our first pass flying south-east parallel to the Russian border, gathering imagery and electronic intelligence, our mission track turned us left about 90° and northwards, directly away from Russia over the Barents Sea. After the turn and perhaps another minute in that northerly direction, we turned 180°, and flew directly towards and perpendicular to the Russian coast.

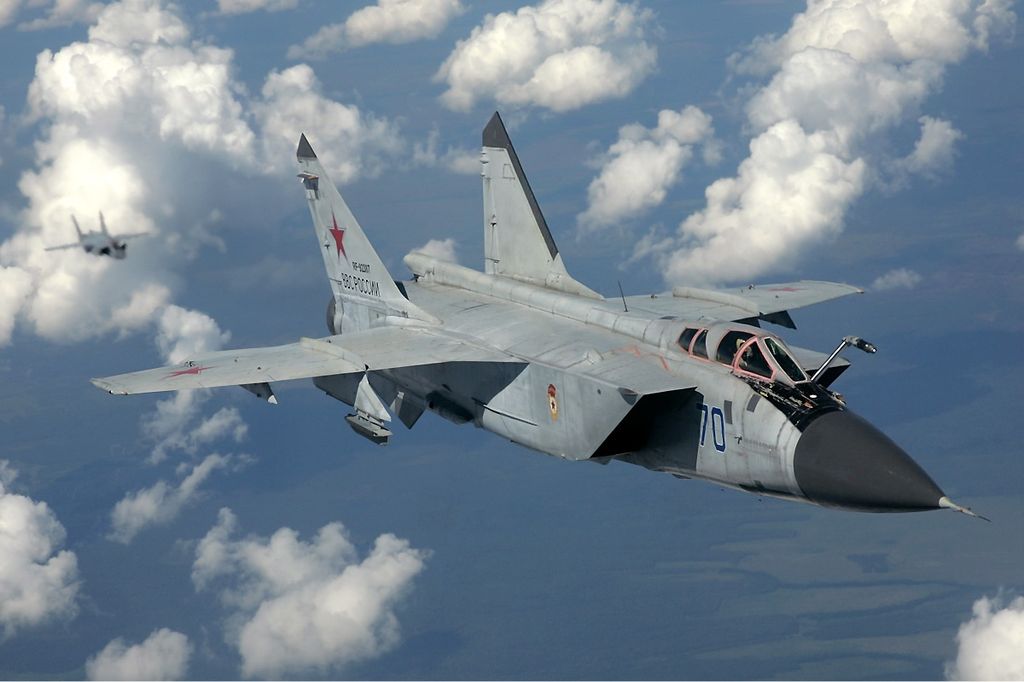

“Our altitude then was probably about 75,000ft. At that altitude, we could see the horizon 335 miles away and see the slight, but noticeable, curvature of the earth. The view was grand. Ahead were miles off the Barents Sea and snow-covered Russia beyond. In the distance far ahead, at perhaps 100 miles, I could see a long, bright white Russian contrail flying directly toward us, but at a much lower altitude. I knew it must be a Soviet fighter, probably a MiG-31, then the newest Soviet supersonic interceptor. I raised my periscope and saw that we too were leaving a long contrail. I knew the fighter could see our contrail as easily as I could see his. Since we were flying a routine reconnaissance track that the Soviets had seen many times, I knew the fighter knew exactly where we would start our 90° right turn to parallel the coast in a westerly direction.

“I imagined the Soviet fighter pilot was much like me, with a love of aviation and trying hard to be one of the very best. I also assumed he had orders to fire his missiles if I was late with my turn and slipped over Soviet territorial waters to within 12nm of Soviet land, and I assumed the pilot would like nothing better than an opportunity to fire his missiles at an SR-71 Blackbird. Just three years prior, on 1 September 1983, a Soviet fighter shot down a Korean Air Lines 747 that accidentally crossed into Russian airspace north of Japan, killing all 269 aboard. Certainly, the SR-71 Blackbird would be a prized target.

“I believed the Soviet fighter would not fire his missiles as long as we stayed on our usual track, but I also knew he or his ground controllers could mistake our position as being closer than we actually were. In the 1980s, we were not too concerned about missiles as long as we maintained our high altitude and high speed. From my previous years of flying intercepts in the F-4 fighter, I knew the newer MiG-31 would still have difficulty maneuvering to the required launch envelope even if he knew our exact flight path. Also, in the high altitude thin air, we believed that missile maneuverability, range, and proximity fuses were not adequate to bring down the Mach 3 Blackbird. For radar-guided missiles, our low radar reflectivity further decreased the missile ‘probability of kill’, and we had a jamming capability for further assurance. I knew our contrail could help him visually put his piper on us for a heat-seeking missile lock-on’. We had no defenses like flares against heat-seeking missiles, but again, we believed that the missile ‘probability of kill’ was very low due to our high speed and altitude. I was determined to fly the track as planned and get the pictures.

“Flying straight toward each other in our supersonic jets, I was reminded of two gallant medieval knights galloping full speed toward each other, only I did not have a weapon. For survival, Curt and I depended on accurate navigation to keep us just outside Soviet territorial waters to prevent a launch, and we depended on our superior speed and altitude in case missiles were launched.

“The fighter’s contrail was holding constant altitude and was heading straight toward us, but far below, perhaps altitude 40,000ft I guessed. I imagined he might be accelerating for a possible steep climb toward our altitude. I watched our distance indicator count down to our turn point, decreasing a mile every two seconds. As always, I was prepared, if necessary, to start the turn manually with the autopilot roll wheel or with the flight control stick, but at our turn point, the autopilot automatically initiated our 90° turn to the right.

“Our 90° turn toward the west was programmed for 32° of the bank. In the turn, I kept a close watch on my instrument panel as always, ready to handle any malfunction. During my instrument crosscheck, I turned my head frequently to watch the fighter’s contrail and saw that he was in a very steep climbing turn toward us. Perhaps a minute into my turn, while turning my pressure suit helmet with my hands so that I could see behind, I saw the grey metal of the fighter, low at my left 7:30 position, at the top of his steeply climbing contrail. We were still in our right 32° banked turn, but I could see him, barely larger than a dot. I could not discern any identifying features like twin tails or distinctive shapes. From my F-4 experience with intercepts and visual acuity, my best guess is that 8 miles were his closest approach. He appeared to run out of airspeed at the top of his contrail, at maybe 65,000ft or about 10,000ft below us. I saw his nose drop below the horizon and fall away. Curt and I stayed on course and got the pictures.

“During my three years of flying overseas reconnaissance missions, I frequently saw contrails far below of potentially hostile fighters, but that day, above the Arctic Circle over the Barents Sea, was the only time I saw a Soviet fighter get close enough that I could actually see metal, though barely larger than a dot and only because our routine track was predictable. Back at Mildenhall, during our debriefing, our intelligence officer told us, with near certainty, that the interceptor was a MiG-31, the premier Soviet supersonic interceptor at that time.”

In the back seat with Ed on Oct. 6, 1986, intercepted was Maj Curt Osterheld. He recalls:

“Ed’s description of operations in the Barents Sea is perfect. We knew that the mission was strategically critical in keeping an eye on the Soviet ballistic missile submarine fleet. But we were also aware that if something went wrong with the airplane, the crew did not have many options. Given that we were operating under the rules of the Peacetime Aerial Reconnaissance Programme (PARPRO), our path was predictable, and the Soviets used us for ‘training’… both for the surface-to-air missiles and fighter intercepts. I do have a very clear memory of turning westbound away from Novaya Zemlya (a.k.a. Banana Island). Looking out the right window and with the help of the mirrors, I could see we were pulling a fat contrail at 75,000ft. Looking down I could see a pair of circular contrails, which, I assumed, were Soviet fighters setting up for a ‘practice’ intercept. We believed that the only chance an interceptor (MiG-31) would have at a decent shot was a ‘beak-to-beak’ pass. I believed like Ed, the velocity of closure and geometry of the required maneuver gave a very low PK (Probability of Kill) to this shot.”

Photo by U.S. Air Force and Dmitriy Pichugin via Wikimedia Commons

Lockheed Blackbird: Beyond the Secret Missions (Revised Edition) is published by Osprey Publishing and is available to order here.