Although the most plausible explanation is that the missile had not reached its arming time when it shot past the crazily jinking RA-5C, no one is certain why it did not detonate

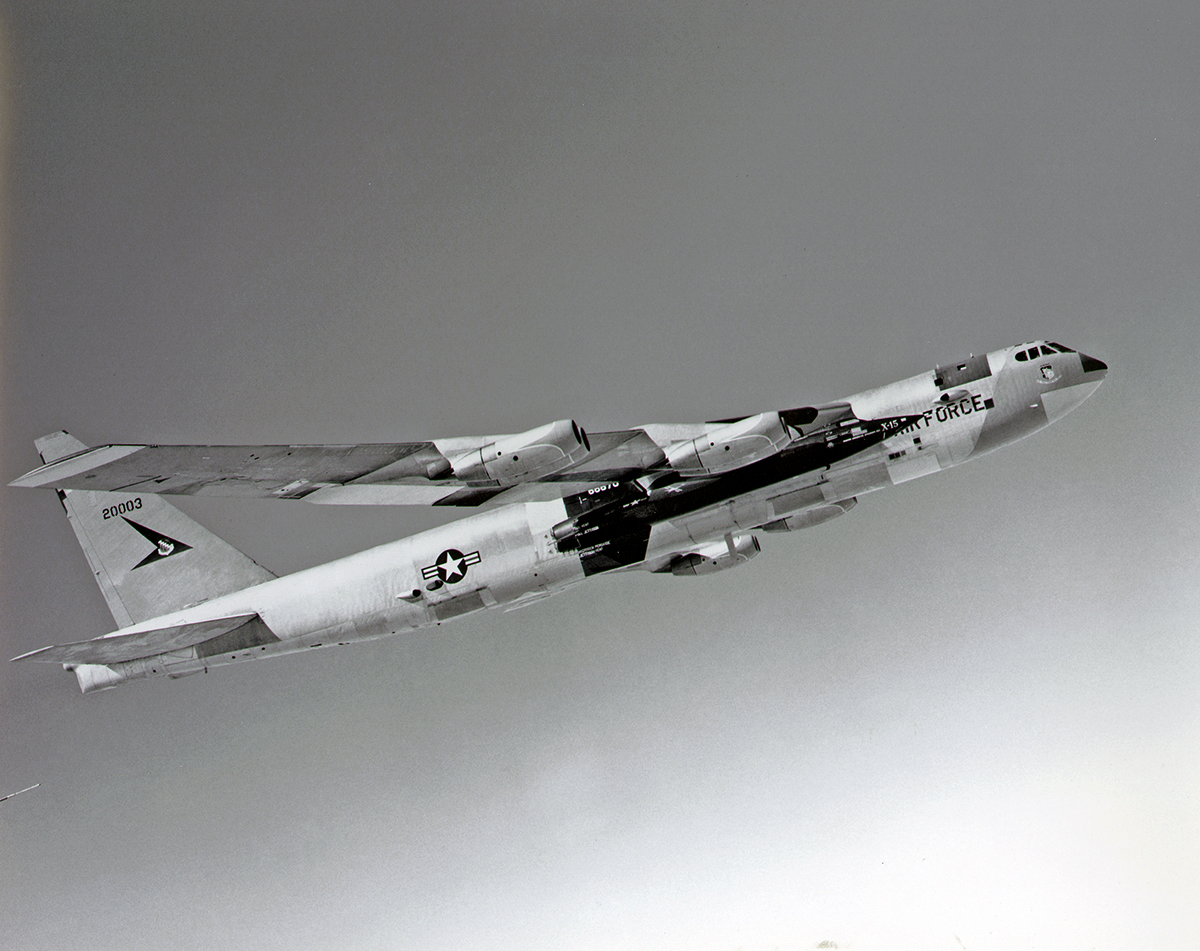

North Americans created the carrier-based supersonic bomber known as the A-5 Vigilante for the U.S. Navy. It only had a relatively brief stint doing nuclear strikes (replacing the Douglas A-3 Skywarrior). However, it was extensively used in the Vietnam War in the tactical strike reconnaissance capacity as the RA-5C.

Medium-level, risky reconnaissance missions (like the one described in this article) began in August 1964.

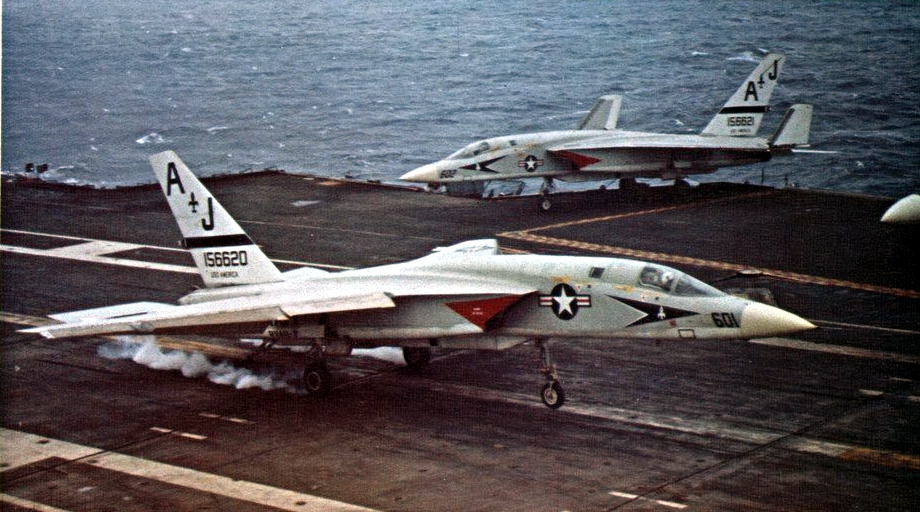

Lt Cdr Barry Gastrock and Lt Emy Conrad, flying the RA-5C Vigilante BuNo.156624 of Reconnaissance Attack (Heavy) Squadron Six (RVAH-6), with the call sign “Field Gold 602,” from USS Kitty Hawk (CVA-63), accidentally captured an amazing photo on March 1, 1971, while performing one of these missions over North Vietnam.

According to Robert R. Powell in his book RA-5C Vigilante Units in Combat, their intended course crossed over itself to permit the crew to capture the Song Ca River in its entirety on camera.

This location was deep inside the SAM envelopes around the city of Vinh.

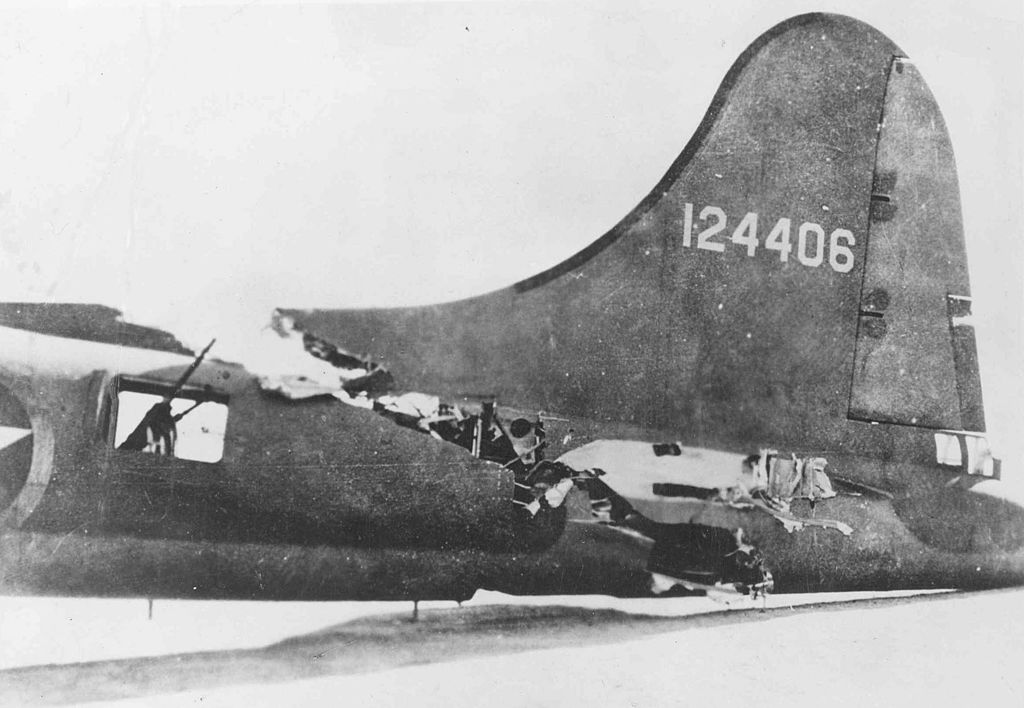

Less than four minutes after passing through the same village in a westerly direction, the Vigilante, heading south, reappeared over the river juncture at Hung Nghia. On the jet’s initial pass over the area, AAA had been patchy, and there had been no missile warnings when Lt. Conrad saw a flash in his viewfinder, heard a “whumpf,” and was thrown against his seat-straps. The crew quickly “had their feet wet” and then made a simple landing back on the Kitty Hawk because the coast was not far away.

A photo interpreter stopped in surprise as she moved the six-inch-wide film from one enormous spool to another across the light table a little while later in the ship’s intelligence center. The vertical camera of the Vigilante captured an SA-2 surface-to-air missile (SAM) that was still gaining altitude perfectly.

The crew was called to see the near-miss. They assumed the SAM passed next to the RA-5C as Lt Cdr Gastrock made a sharp turn to return home because there was no terrain visible in the picture. With knowledge of the SA-2’s size and the camera’s focal length, the photogrammeters calculated that the missile had passed within 104 feet of the Vigilante’s belly.

Although the most plausible explanation is that the missile had not yet reached its arming time when it shot past the crazily jinking RA-5C, no one is certain why it did not detonate.

Despite the Vigilante’s speed and agility, 18 of these aircraft were destroyed in battle during the Vietnam War: 14 by anti-aircraft fire, three by surface-to-air missiles, and one by a MiG-21. As attrition replacements, 36 further RA-5C aircraft were manufactured from 1968 to 1970 in part as a result of these combat losses. These planes were very different from earlier RA-5Cs. These were worthy of being dubbed RA-5Ds thanks to improved engines, Leading Edge Extensions over the intakes, changed intake geometry, and other upgrades, but the existing moniker was kept. Since the BuNo. for this most recent batch of Vigilantes begins with the number 156, they are known as the 156 Series aircraft (some earlier RA-5Cs were rebuilt to the same standard so there are exceptions).

Photo by Emy Conrad / U.S. Navy and U.S. Air Force