In Southeast Asia,

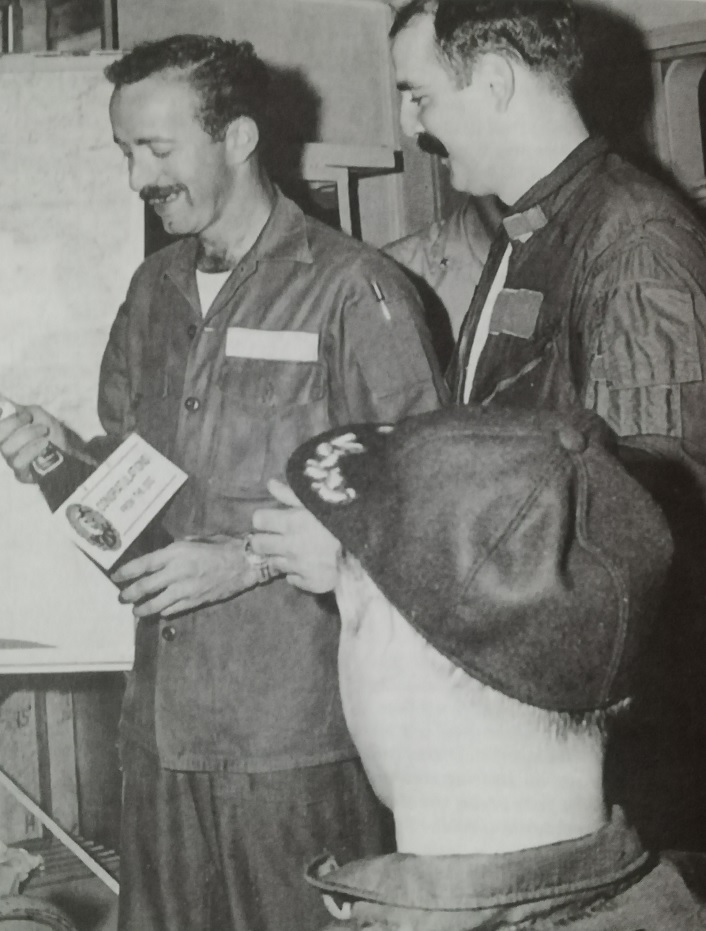

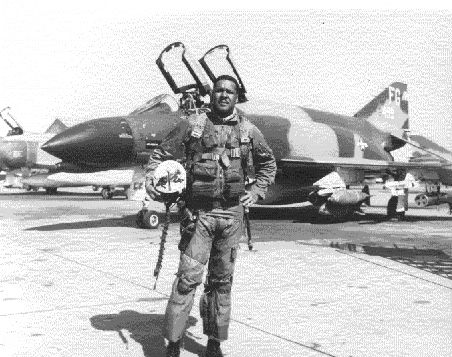

Gen. Chappie James served as deputy commander for operations and later vice wing commander of the 8th TFW. Along with Robin Olds, James formed a strong leadership and combat team, inevitably dubbed “Black Man and Robin.”

The Gen. Daniel Chappie James Memorial Bridge is the name of the new Pensacola Bay bridge, according to the Pensacola News Journal.

The campaign to rename the bridge in honor of the illustrious U.S. Air Force (USAF) general was led by former congressional candidate Cris Dosev, who presented the idea to the Escambia County legislative delegation in December 2019 at a local public hearing ahead of the legislative session.

The idea was well received by local legislators, and Sen. Doug Broxson proposed that Dosev schedule a meeting with his office.

James was the first African American four-star general in the U.S. Air Force. James was appointed as the Commander in Chief of the North American Air Defense Command (NORAD) on September 1, 1975, a position he held until his retirement on February 1, 1978. In 24 days, he passed away.

James, a veteran of World War II, the Korean War, and the Southeast Asia War, described his feelings on his experience as an American serviceman as follows: “I’ve fought in three wars and three more wouldn’t be too many to defend my country. I love America and as she has weaknesses or ills, I’ll hold her hand.”

His son, Claude James, stated that the family was in favor of renaming the bridge in the general’s honor.

“It’s a perfect acknowledgment of one America’s greatest leaders and defenders who never forgot where he came from,” the son said. “And throughout his history-making career, he gave credit to his mother’s little school on Alcaniz Street that prepared him to succeed in and love and defend his country.”

Dosev, a former pilot with the United States Marine Corps, claimed that he had always admired James.

“Everyone is talking about the fact that we no longer have heroes to emulate,” Dosev said. “Well, we do. We do, and that hero is Gen. Chappie James. And I think that the community in a large part has forgotten who this man was, and what he did, and that’s sad.”

“A statue of James will be erected in the new park near the bridge landing on the Pensacola side,” Dosev added, in addition to renaming the bridge in the general’s honor. Dosev intended to place a static display of an F-4 Phantom II fighter jet behind the statue.

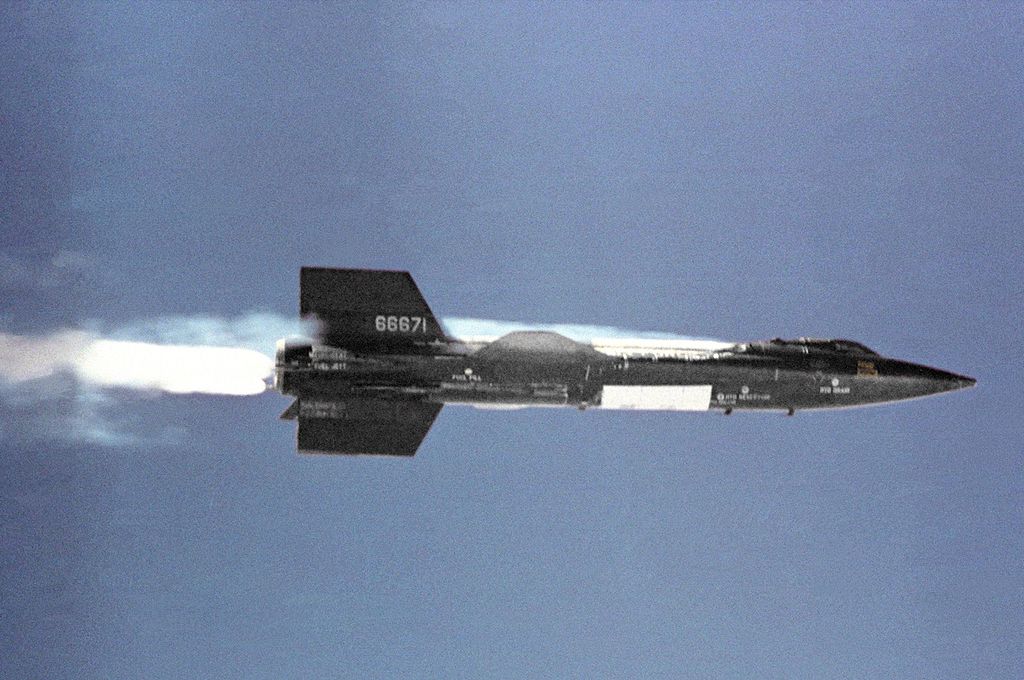

During Operation Bolo in the Vietnam War, James piloted an F-4.

He served in Southeast Asia as the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing’s vice wing commander and deputy commander for operations when he met Robin Olds, an ace pilot, and wing commander, whom he had already known during his time at the Pentagon. The two guys inevitably earned the nickname “Black Man and Robin” for their effective leadership and combat abilities.

Perhaps the pinnacle of their professional collaboration was Operation Bolo. It was an aerial trap designed by Olds for adversary MiGs that had been hitting heavily laden F-105 fighter bombers flying to their targets while dodging US fighter escorts.

Beginning the operation in January 1967 was a force of F-4 fighters posing as an F-105 flight. The F-4s made use of F-105 refueling altitudes, approach routes, airspeeds, radio call signs, and more distinctive indicators. According to Aces and Aerial Victories, the official history of the USAF in Southeast Asia, the F-4s were also given ECM pods for the first time to deceive the enemy’s missile and flak tracking and acquisition radars.

This deception force had four F-4C aircraft per flight. At 3:00 p.m. local time, Olds piloted the first flight and arrived right on target over Phuc Yen, northwest of Hanoi. No MiGs.

Unbeknownst to Olds, enemy ground control had forced a 15-minute delay in MiG takeoffs owing to cloudy conditions.

Then James led Ford Flight, the second group of F-4s. It emerged from the clouds five minutes after Olds, on schedule. The MiGs emerged at that same moment. The subsequent melee may have been the biggest fighter engagement of the Vietnam War.

Three MiGs attacked James’ flight right away. One came from the 6 o’clock low and two from the 10 o’clock high. James unexpectedly found himself flying very next to his opponent as he transitioned from a steep right break to a left bank, in what he subsequently described as a “strange encounter.”

“For a split second, [he] was canopy-to-canopy with me. I could clearly see the pilot and the bright red star markings,” James said in an after-action report. James barrel-rolled to gain separation for attack and fired one Sidewinder. It missed as the MiG broke hard left. But the North Vietnamese pilot had evaded James only to put himself in the flight path of Ford Flight’s No. 2 aircraft, flown by Capt. Everett T. Raspberry Jr. A few more maneuvers, and Raspberry put a Sidewinder up the MiG’s tailpipe.

By the time it ended, 12 F-4s had engaged 14 MiGs, winning seven confirmed battles without losing any.

One of the Vision Pensacola organizers, Pensacola urban planner Alan Gray, supported the idea and created renderings of what the memorial at the base of the Bay Bridge would look like. Alan Gray also submitted the winning design for the new bridge.

The bridge already had a name under Florida law, the Philip D. Beall Sr. Memorial Bridge, thus, it presented one of the remaining obstacles to designating it after James.

After being chosen as the Senate’s president in 1943, Pensacola state senator Beall passed away while still in office. Kirke Beall, his grandson, has fought to maintain the name on the bridge.

Beall did not object, nevertheless, to the bridge sharing a name.

“As long as it’s a good person and they are deserving of it, I am glad to have my grandfather’s name next to it,” Beall said.

“My motivation is to promote Gen. Chappie James,” Dosev said. That’s my motivation… I don’t want the memory of Chappie James to be forgotten.”

Photo by Pensacola News Journal and U.S. Air Force