Captain Magill and his wingman thought they had caught the two Fulcrums off guard when the MiG-29s suddenly began maneuvering and turned aggressively toward their formation…

An F-15C assigned to the 18th Wing has a unique story in its past.

As told by James D’Angina, 353rd Special Operations Group historian, in the article Kadena F-15 holds the last Marine aerial victory, during the 1991 Gulf War, the Eagle scored the last recorded air-to-air victory by a U.S. Marine Corps pilot.

On Jan. 17, 1991, Marine Capt. Charles “Sly” Magill, flying F-15C 85-0107, was leading a flight of eight F-15s on the second day of the war. Captain Magill, a Marine F/A-18 Hornet pilot, and Top Gun graduate, was on exchange duty with the Air Force’s 58th Tactical Fighter Squadron, 33rd Tactical Fighter Wing (Provisional).

Captain Magill was one of four weapons experts within the squadron and was entrusted with leading the first daylight mission for the unit. The F-15s provided air cover for a strike package against Al Taqaddum and Al Assad airfields.

After refueling with a KC-135, an E-3 Sentry alerted the captain to the presence of two MiG-29 Fulcrums near their target area. He split his flight into two four-ship formations using the call signs ZEREX and CITGO respectively. CITGO continued with their primary cover mission toward Al Taqaddum and Al Assad, while Captain Magill’s ZEREX flight turned towards the Fulcrums.

The aircraft in Captain Magill’s formation had just picked up the enemy aircraft on the radar when surface-to-air missile threat warnings went off. The four F-15s released their wing tanks and took evasive maneuvers while deploying chaff and flares. The maneuvers succeeded in defeating the SAM radar locks.

As soon as the SAMs were no longer a threat, the ZEREX flight regrouped and resumed stalking the Iraqi Fulcrums.

Captain Magill and his wingman thought they had caught the two Fulcrums off guard when the MiG-29s suddenly began maneuvering and turned aggressively toward their formation. However, the MiGs were unaware of the F-15s that were now tracking them; they had their sights on a different target, a Navy F-14 Tomcat. Unknown to the doomed Iraqi pilots, they had just gone from hunter to hunted.

Captain Magill and his wingman, Captain Rhory “Hoser” Draeger, carefully maneuvered their aircraft into firing position while the remainder of the ZEREX flight provided cover. Captain Draeger was the first to get a solid radar lock and fired a single AIM-7 Sparrow at the lead MiG.

Immediately after Captain Draeger’s shot, Captain Magill fired his own Sparrow at the MiG’s wingman. Initially fearing that his missile had malfunctioned, he quickly fired a second AIM-7 to ensure that his targeted MiG would not escape.

Captain Draeger’s missile hit his target head-on, destroying the aircraft.

Despite his fears, Magill’s first missile had not malfunctioned. It properly tracked and struck the second Fulcrum’s right wing. His second hastily fired Sparrow impacted the center of the expanding fireball, obliterating it. Magill’s victory was the first and only Marine air-to-air kill of the war and the last aerial victory earned by a Marine aviator since the Vietnam War.

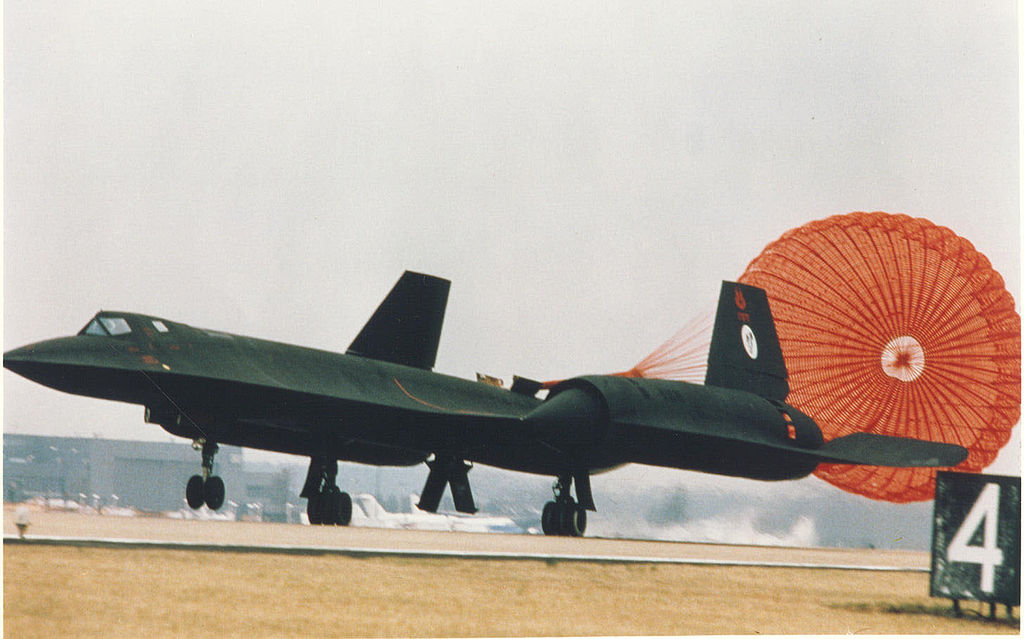

Captain Magill’s aircraft, F-15C 85-0107, now performs its air superiority mission with the 44th Fighter Squadron at Kadena Air Base.

It proudly bears a green “kill” star below the left-side canopy rail for the 1991 mission—a lasting testimony of the skill and dedication of American service members. The aircraft is one of seven F-15s with the 44th and 67th Fighter Squadrons to have scored air-to-air victories during Desert Storm and are still serving as frontline fighters.

victory by a U.S. Marine Corps pilot with a MiG-29 Fulcrum kill. (U.S. Air Force illustration by Naoko Shimoji)

Photo by U.S. Air Force