These missions amply demonstrated the opportunities provided by transport aircraft

Italian North Africa was the name given to the territory that would eventually become modern-day Libya by Europeans from 1912 to 1927. Idris al-Mahdi al-Sanussi (later known as King Idris I of Libya) and Umar Mukhtar were two of the most well-known figures in the Libyan resistance at this time (eponymous hero of the film Omar Mukhtar, Lion of the Desert in which his character was played by Oliver Reed). Both were based in the eastern province of Cyrenaica, rather than the western province of Tripolitania. The southern province of Fezzan, meanwhile, didn’t become well-known until the latter phases of this conflict.

In Tripolitania, an independent state was proclaimed practically immediately after the Great War, according to Air Vice Marshal Gabr Ali Gabr and Dr. David Nicolle in their book Air Power and the Arab World 1909-1955 Volume 3 Colonial Skies 1918-1936. The new state, which went by the name Al-Jumhurya al-Trabulsiya (The Republic of Tripolitania) and had its capital in Aziziya, was established informally during the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 after being declared by a number of local leaders.

But, these Libyan authorities did not envision the expulsion of all Italians from their nation. They desired the establishment of Italian commercial domination as opposed to the Italian occupation. The Republic of Tripolitania is frequently said to as the Arab World’s first modern republic. Sadly, the Republic of Tripolitiania received little support from nations other than Libya and was brutally suppressed by Italian forces.

Once Giuseppe Volpi, a politician, and businessman took over as governor on July 16, 1921, and succeeded Luigi Mercatelli, Tripolitania was finally reclaimed. Volpi would later receive the title of Count of Misratah as recompense. Moreover, he established the famed Venice Biennale Arts Festival. In Libya, however, Giuseppe Volpi’s first task was to revive the sagging morale of sometimes poorly supplied Italian garrisons. A quick offensive then occurred, evidently taking the possibly complacent Libyan resistance by surprise.

Early on January 26, 1922, a mixed force made up of police, Italian, Eritrean, and local troops landed on the coast outside of Misratah, which they then captured. Tripoli and its outlying settlements were firmly back under Italian control in little more than a year, and between 1923 and 1925 also the coast and northern lowlands. Next, Italian forces seized control of the deep desert and the central semi-desert areas. By the end of the 1920s, this offensive had brought Italian forces close to the Fezzan border.

Italian Air Force aircraft participated in practically every phase of this campaign, but the most impressive deployment of air power came from a circumstance where Italy might have lost just a fortnight after its initial success at Misratah. On February 9, 1922, when so-called “rebels” cut the railway connection, the 10th Battalion Eritrean Askari was under siege at Aziziya. On March 19, the supporters of resistance leader Farad Bey took over Zuwarah, and the railway line connecting Tripoli and Zuwarah was also destroyed.

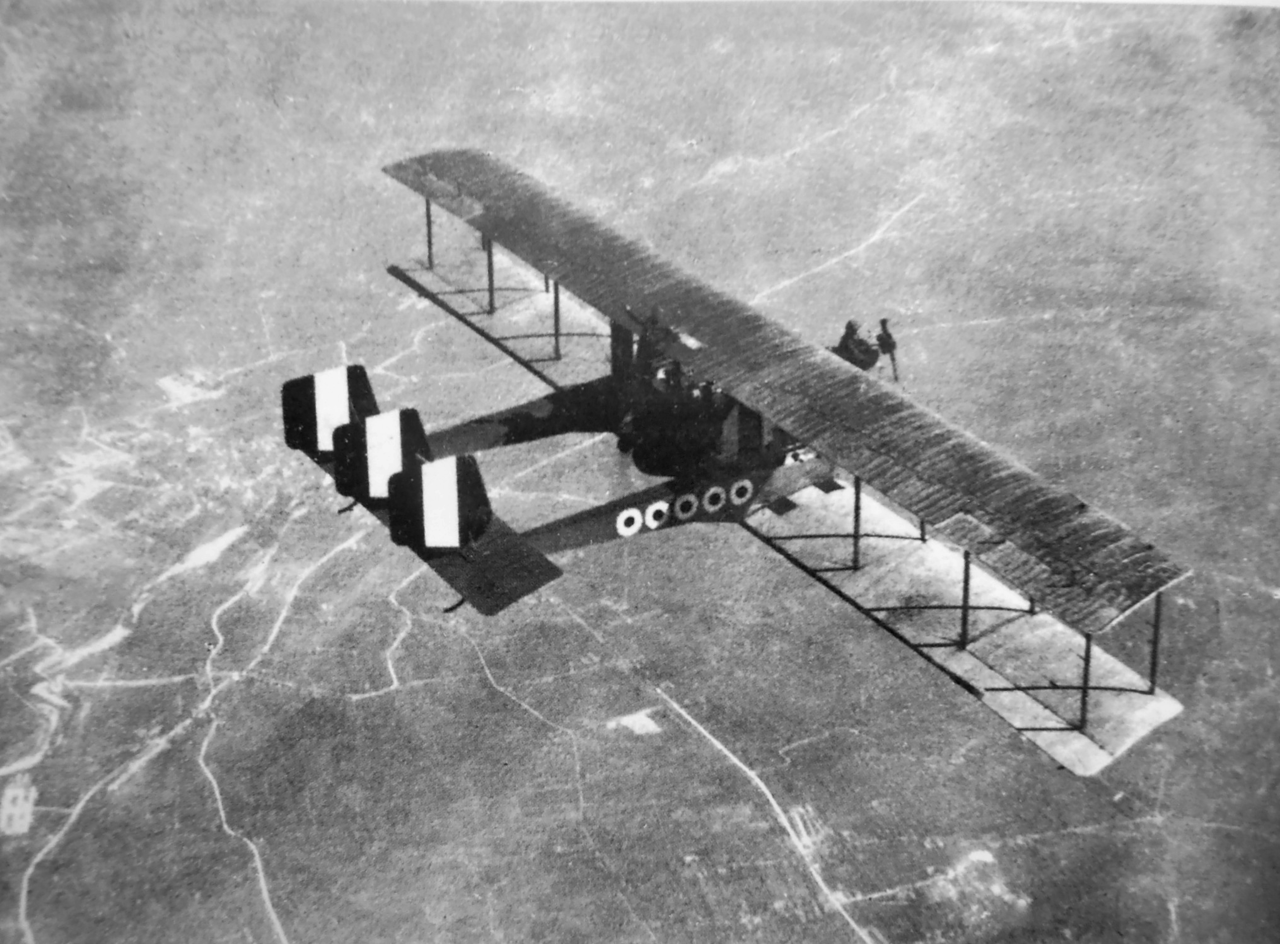

A few Caproni tri-motors, originally built as long-range bombers during the First World War, transported fresh troops to the outpost while also evacuating civilians and injured soldiers. With no other means of communication remaining between the roughly 1,000 troops in Aziziya and the main Italian forces in Tripoli. They received help from a few smaller machines for this. Due to the number of participants, this was the first real military airlift in aviation history.

Col. Siciliani, Col. Riccardo Moizo, and General Commander of the Italian Air Force General Pietro Badoglio, Chief of the Italian General Staff, arrived in Tripoli on April 26 to assess the situation. During the initial Italian invasion of Libya in 1912, Moizo had been shot down and taken prisoner.

Notwithstanding how amazing this airlift was, it was evident that it was unable to provide the Aziziya garrison with what it required to survive a protracted siege. There were simply too few and little of planes available. Three Caproni Ca.33 aircraft and a dozen smaller Ansaldo S.V.A. single- and two-seaters flew daily flights during this emergency. The Capronis usually carried sacks of flour, some of which were placed between the fuel tanks, others between fuel tanks and the center of the Caproni’s three engines, and also in the front observer cockpit. A Caproni could theoretically transport up to 1,200 kg of supplies or a number of passengers by reducing the three-person crew to just two pilots and by carrying half the quantity of fuel that is typically carried.

The Ansaldo S.V.A. 5 single seater, on the other hand, could carry six bags of flour (120kg) strapped to the fuselage where the removed machine guns had been without the aeroplane becoming unbalanced. Yet as Squadron Commander Lieutenant R. Armellini discovered when flour spilled into his cockpit from a shattered sack, flying a plane in this state was anything but simple. He had to land quickly as a result, which hurt his S.V.A. One Caproni pilot, Sergente Zagni, was killed when two engines failed simultaneously, while another S.V.A. was injured while landing on a rocky track adjacent to al-Aziziya fort.

In addition to carrying injured Eritrean soldiers and those whose term of enlistment had expired back to Tripoli, these Capronis also transported a number of civilians, including women and children. A new company of Eritreans, together with its officials, took its place.

This amazing airlift lasted until April 10 when it was put on hold while an Italian Army column led by Colonel Rodolfo Graziani, a 39-year-old enthusiastic fascist, arrived. By that point, the Capronis and S.V.A.s had flown 335 times, delivering 278 soldiers, 213 reinforcements from Tripoli to Aziziya, 42 tons of food, 3 tons of other materials, and 53 civilians. Forty wounded members of Graziani’s force were also transported back to Tripoli after his column relieved the siege. These missions taught a lesson that future European imperial powers would not overlook regarding the potential of transport aircraft, particularly in colonial battles.

Air Power and the Arab World 1909-1955 Volume 3 Colonial Skies 1918-1936 is published by Helion & Company and is available to order here.

Photo by Unknown