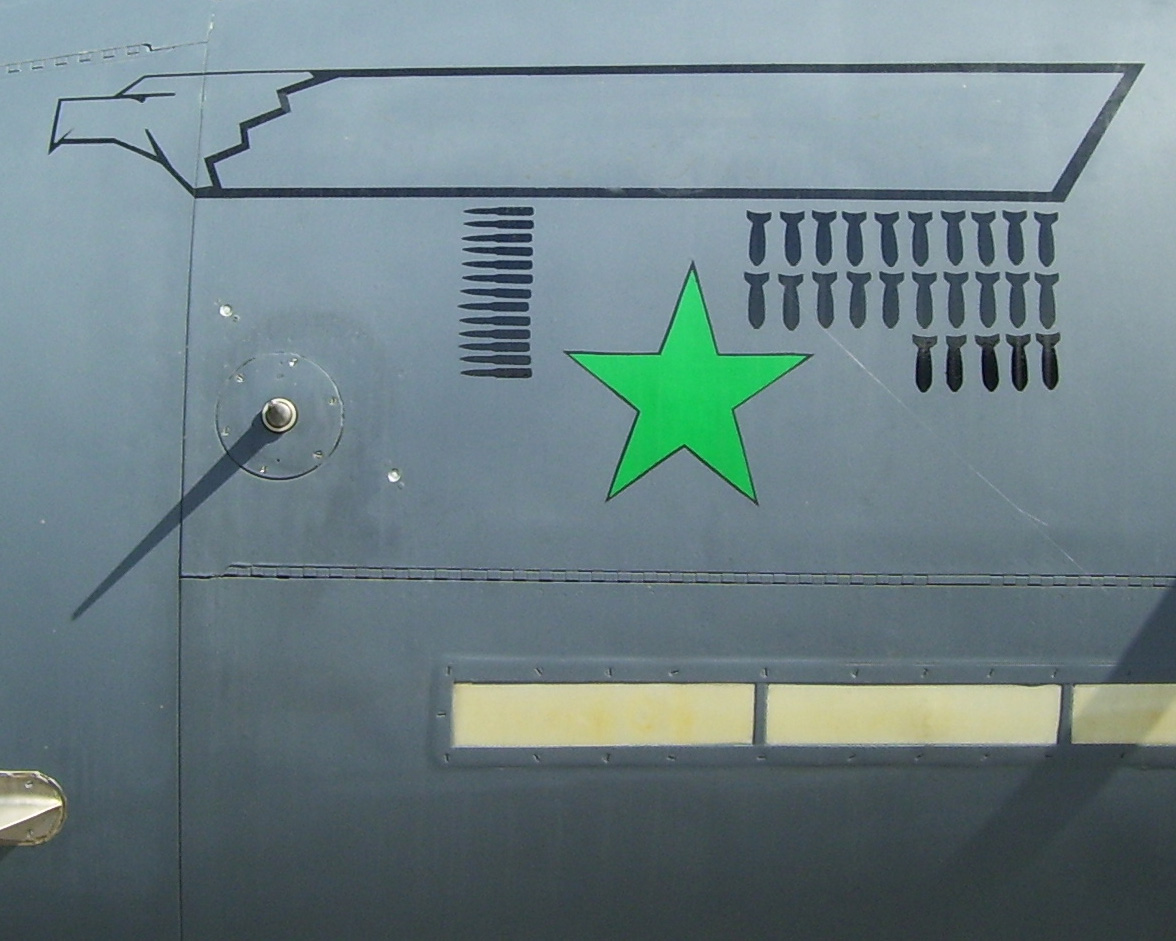

One of the most unique air-to-air kills in aviation history is ascribed to “Chiefs” from 335th Tactical Fighter Squadron (TFS, now known as 335th Fighter Squadron, FS) during Operation Desert Storm F-15E Strike Eagle #89-0487, or “487” for short

The F-15E Strike Eagle was created to satisfy the US Air Force’s (USAF) requirement for air-to-ground missions. It took off for the first time in December 1986 from St. Louis. In addition to having an infrared targeting and advanced navigation system, which enables the Strike Eagle to fly at night or in bad weather at a low altitude while maintaining a high speed, the Strike Eagle can carry 23,000 pounds of air-to-ground and air-to-air weaponry, shielding it from enemy defenses.

April 1988 saw the delivery of the F-15E’s first production model to the 405th Tactical Training Wing at Luke AFB in Arizona.

During Operation Desert Storm, which was launched between January 17, 1991, and February 28, 1991, with the intention of freeing Kuwait from the Iraqi invasion, the F-15E was used for the first time in combat. One of the most unique air-to-air kills in aviation history was attributed to F-15E Strike Eagle #89-0487, or “487” for short, from the 335th Tactical Fighter Squadron (TFS, now known as the 335th Fighter Squadron, FS) “Chiefs” during this combat.

The first air-to-air kill for an F-15E Strike Eagle took place on February 14, 1991, during an air encounter by Capts. Richard T. Bennett, pilot, and Daniel B. Bakke, weapon systems operator (WSO).

“On one flight, we used a laser-guided bomb [LGB] to shoot down a helicopter,” Bennet explained to Barry D. Smith for his article Tim Bennett’s War. “This occurred on February 14, Valentine’s Day. The mission was a Scud CAP [combat air patrol] in northwestern Iraq. During the Scud CAPs, we would look around with either the FLIR targeting pod or the radar to find the mobile Scuds. My wingman had twelve Mk. 82s, and I had four GBU-10s-2,000-pound LGBs-four AIM-9s, and two external fuel tanks. I was leading the flight.

“Our CAP time on this mission was 1:00 to 3:00 in the morning. We went up and hit the tanker, then proceeded north. Our patrol area started up at Al Qaim, near the Syrian border, and ran east about halfway to Baghdad, south to just beyond H-2, and then back to the Syrian border.

“The weather was bad that night, with clouds from about 4,000 feet to about 18,000 feet. We were cruising above the weather, waiting for AWACS [an E-3 Airborne Warning and Control System aircraft] or someone else to pass us some coordinates on some Scuds.

“AWACS gave us a call and said that a Special Forces team was in trouble. They had been found by the Iraqis, who were moving to cut them off. We had ten to fifteen Special Forces teams in the general area looking for Scuds. This team was about 300 miles across the border.

“Five Iraqi helicopters were in their area-about fifty miles to our west. As we headed in their direction, I put my wingman in a four-mile trail formation behind me because I had to go down through the weather. When I was about fifty miles from the team, Capt. Dan Bakke, my back-seater, began working the radar to look for the helicopters. We got contacts on them moving west to east, just like the AWACS had said.

“Dan and I started talking about what we were going to do. We knew there were helicopters down there, but if we were going to shoot them down, we wanted confirmation that they were bad guys. We called up AWACS, call sign Cougar, and asked them if there were any friendly helicopters in the area. The AWACS controller said, ‘We don’t have any friendlies in the area. Any helicopters you find, you are cleared to shoot.’

“We got a little closer and kept going down to get below the weather. I wanted to confirm, one more time, before we lost contact with AWACS, that these were definitely bad guys and not some of our Special Forces helicopters coming to get the team. We had a few based in Syria that would have been following the same general course and could have gotten to the area fairly quickly. AWACS confirmed there were no friendlies in the area.

“We continued to press in and were down to about 2,500 feet along the major road between Baghdad and the Syrian border. That area was always hot with a lot of AAA. I was working the radar, and Dan was working the high-resolution FLIR in the targeting pod to find the helicopters. When we popped out of the clouds fifteen to twenty miles from the team, Dan could see the helicopters with the pod. They were moving pretty much abreast, with the lead out in front in the middle. They were still moving west to east. They were moving and stopping at regular intervals.

“There was also a group of troops on the ground to the east of the team. We started getting AAA fire from these troops. To us, it looked as if they were trying to herd the team with the helicopters into the troops to the east. The helicopters were keeping an even distance from each other, and we figured they might be dropping off troops to help herd the team.

“The image on the pod was good enough to identify the helicopters as probable [Mi-24] ‘Hinds,’ five to ten miles out. Hinds can carry troops and are heavily armed with rockets and machine guns. As soon as the helicopters picked up and started moving, we were getting hits off them on the radar. The radar would stay locked on them when they were on the ground because the moving rotor blades were picked up.

“Dan and I discussed how we wanted to conduct the attack. We decided to hit the lead helicopter with a GBU-10 while he was on the ground. If we hit him, he would be destroyed. If he moved off before the bomb landed, it would still get the troops he just left on the ground. It would also give the other helicopters something to think about, which might give the team a chance to get away in the confusion. We would then circle around and pop the others as we could. We passed our plan to our wingman and told him to get the first helicopter he saw with an AIM-9.

“By this time, we were screaming over the ground, doing about 600 knots–almost 700 mph. The AAA was still coming up pretty thick. Our course took us right over the top of the Iraqi troops to the east of the team.

“[…] Dan was lasing the lead helicopter. We let the bomb go from about four miles out while the leader was on the ground. Because of our speed, it had a hell of a range on it-more range than an AIM-9. I got AIM-9 guidance going and uncaged a Sidewinder. I was ready to fire the missile as soon as we were in range.

“Just as we released the bomb, the airspeed readout on the radar showed the target at 100 knots and climbing. The lead chopper had picked up and started moving. I said, ‘There’s no chance the bomb will get him now,’ even though Dan was working hard to keep the laser spot on him. I got a good lock with my missile and was about to pickle off a Sidewinder when the bomb flew into my field of view on the targeting IR screen.

“There was a big flash, and I could see pieces flying in different directions. It blew the helicopter to hell, damn near vaporized it.

“We sat there for a few seconds, just staring. By that time, the AAA was getting real heavy and the other helicopters were starting to scatter. I told my wingman to put three Mk. 82 500-pounders on that same spot to get any troops that the helos dropped off.

“We beat up the area with bombs and were going to circle around and come down on them again. I popped up above 10,000 feet and talked to AWACS to tell them what was going on. They said, ‘I understand you visually ID’ed that as an Iraqi helo.’

“I said, ‘No, it’s still dark out here, but I saw a FLIR image of what I took to be a Hind.’

“At that point, my stomach hit the floor. I told AWACS to get the AWACS commander on the radio. Dan and I were thinking, ‘We hit a friendly helo.’ But when we got the AWACS commander on the air, he confirmed that there were no friendlies in the area.

“With that confirmed, I told Dan, ‘OK, let’s go back down and get the rest of the helos.’ We got down low and the AAA was just as bad as before. The helicopters scattered and were running north. My wingman and I were sorting them out and waiting to get within AIM-9 range. We were about ten miles behind and closing fast.

“I was running in on them and getting ready to be a hero and knock a few more down when, all of a sudden, I started seeing flashes on both sides of us. I thought, ‘What have they done? Here we are in the middle of a bunch of SAMs!’

“Then it hit me: Those weren’t SAMs. They were bombs! AWACS had sent another flight in and told them to drop bombs on a set of coordinates. Those coordinates happened to be us!”

Bennet concludes:

“I figured we had pushed our luck far enough, and we got the hell out of there. AWACS gave the orders to that other flight on another frequency. If it had been on ours, I would have heard the bombers’ side of the conversation and could have canceled the drop. I decided we had had enough for one day, but our night wasn’t over yet. We still had fifteen minutes left on our Scud CAP and were directed to a site near H-2. We found a mobile Scud on a launchpad, attacked it, and then headed home.

“The Special Forces team got out OK and went back to Central Air Forces headquarters to say thanks and confirm our kill for us. They saw the helicopter go down. When the helos had bugged out, the team moved back to the west and was extracted.”

Today, “487”is still assigned to the same squadron it made history with in 1991. It’s the Chiefs’ flagship and still has a small green star adorned on the aircraft’s port side representing that moment in the squadron’s history.

Photo by Master Sgt. Lance Cheung, James D’Angina and MSGT STEVEN TURNER / U.S. Air Force