The destruction of the Luftwaffe and its industries was the Eighth Air Force’s top mission in 1943, and its B-17s were dedicated weapons for long-range, daytime precision bombing

The destruction of the Luftwaffe and its industries was the Eighth Air Force’s top mission in 1943, and its B-17s were dedicated weapons for long-range, daytime precision bombing.

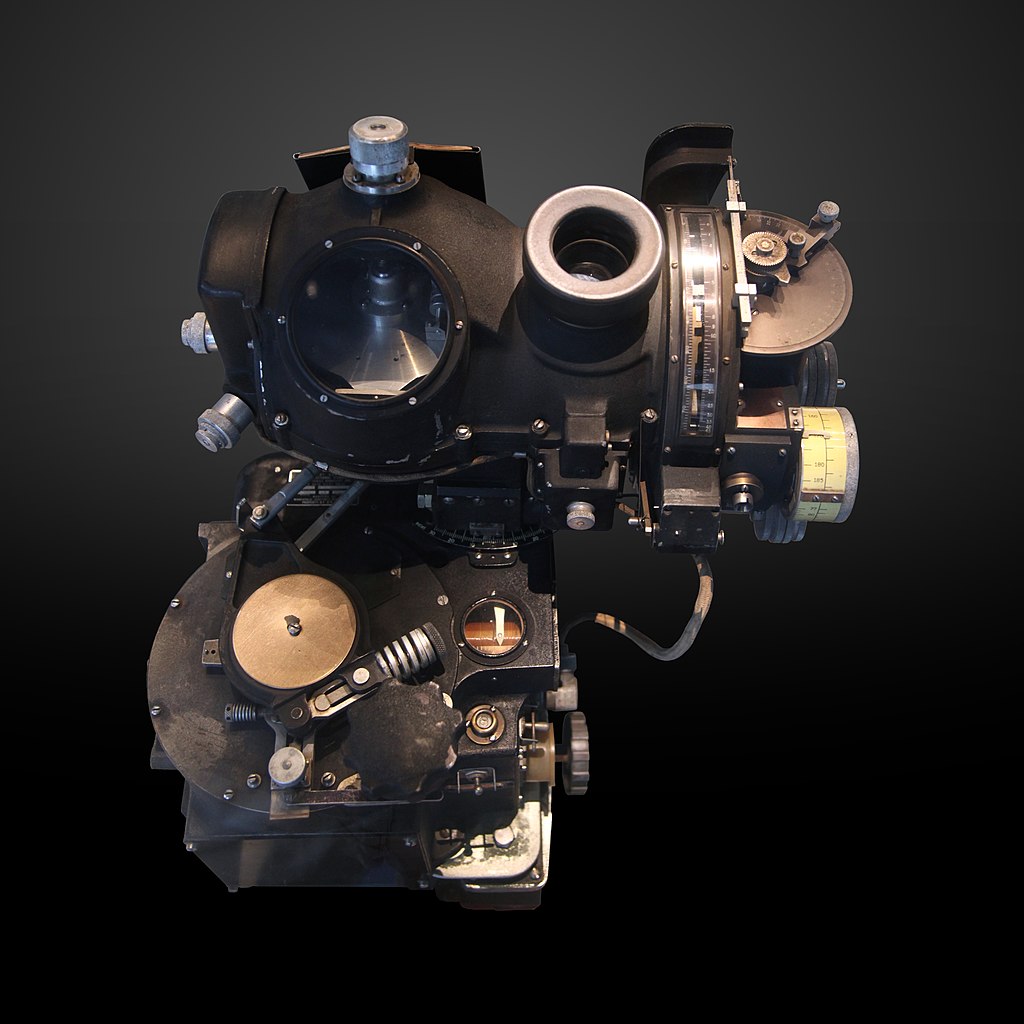

The gyrostabilized Norden M-4 bombsight, developed in the middle of the 1930s, ironically for the US Navy, was one of the factors that led the US Army Air Force (USAAF) to commit to daytime precision bombing, as Marshall L. Michel III explains in his book Schweinfurt-Regensburg 1943. The Norden was ordered by the USAAF for its brand-new B-17s, and tests of the Norden/B-17 combo under perfect weather and visibility conditions revealed that it much outperformed the accuracy of its forerunners and would enable precise bombing from a tremendous height. The Norden garnered much attention from the media, and to increase its mystery, no images or information regarding how it operated was ever made public.

However, the Norden was most effective when used by single aircraft that could independently maneuver to line up on the target. The maneuvering required for the Norden to perform at its peak couldn’t be met in combat, and the Nordennbombsight, with its delicate adjustment, lost much of its value. All aspects of the bombing mission, aside from the brief moments of the bombing run, were dominated by defense-related considerations.

Even under ideal circumstances, more than half of the bombs hit more than 1,000 feet from the target. These circumstances were the best for accuracy and protection from flak, but they would not give enough defense against aircraft strikes in combat. An inferior sight that required less careful adjustment was briefly considered, which would have significantly jeopardized the American bombardment theory’s foundational accuracy ideal.

It was necessary to create techniques to hit the German objectives with sufficient accuracy while maintaining the bombers in their tight defensive formation since the Eighth Air Force Bomber Command hoped to survive over Germany unescorted by their heavy firepower and tight formations. Flak was also a danger to the target, even if German fighters were the main danger. Flak hindered efficient bombing operations more by forcing the aircraft to bomb at high altitudes, which decreased accuracy, than by actually killing or injuring the bombers.

Because of the German fighter defenses, it was clear that each bomber could not disperse and conduct a separate bomb run. As a result, formation bombing, in which all bombers drop their bombs simultaneously with the lead aircraft, was successfully tried as early as January 1943. The VIII Bomber Command’s Operational Research Section strongly advised using this method in March 1943. Although it would be difficult to maneuver the large formations onto the bombing run and the resulting bomb pattern would scatter more widely than was ideal for the desired accuracy, in July 1943 VIII Bomber Command’s leadership agreed and ordered that the combat wings begin to plan to use formation bombing.

The wings had to build well-coordinated pilot, navigator, and bombardier teams in order for formation bombing to succeed. In order to do this, VIII Bomber Command ordered the formation of special “lead crews” in each squadron at each station. Squadrons were required to identify their top bombardiers before joining with a carefully chosen navigator. The lead crew pilot was picked for his ability to fly smoothly and make modifications gradually to keep the formation together. These lead crews alone would be responsible for identifying the target, guiding the unit on the bomb run, finding the release point, and delivering the order to release.

Only three other aircraft in each group carried bombsights in case the lead aircraft was shot down: the high and low squadron leaders and the wingman of the lead aircraft. The other crews’ task was to remain in strengthened defensive positions and release when the commander was freed.

To serve as squadron or group lead crews on combat missions, the lead crews received extensive training. They frequently carried an extra navigator, and typically an officer pilot served as the tail gunner, giving the pilot advice on the formation’s status. Finally, the lead crew’s tour would be curtailed by five missions, and they were only allowed to take part in combat as a lead crew. In addition to these crews, each squadron had two extremely dependable B-17s that were designated as “lead bombers” and outfitted with every device necessary to accurately bomb a target as it became available.

The few seconds before the lead bombardier launched the bombs when he had to carry out his final sighting operation and find the bomb release site, were the most crucial in the entire mission. This required that the lead bomber be kept as close to a constant course without slips, skids, or changes in altitude. VIII Bomber Command decided that a mechanical instrument could maintain this precise position better than a pilot, who might be distracted by flak or advancing fighters.

This automatic flight-control equipment (AFCE), sometimes known as an automatic pilot, was created and successfully deployed for the first time on March 18, 1943. By synchronizing sighting and pilotage, the AFCE allowed the bombardier to control the aircraft on the bomb run with mechanical precision, allowing him to produce a steadier bombing run than even experienced pilots could. The AFCE was soon given to all of the B-17s that had been assigned as “lead” aircraft.

However, as the Combined Bomber Offensive in 1943 gained momentum, two infamous raids compelled the Americans to reconsider the viability of long-range daylight precision bombing. The Americans lost 60 bombers and hundreds of troops when they launched a massive and ingenious double-strike against the factories in Schweinfurt and Regensburg, flying far outside the P-47 escorts’ range. This temporarily crippled VIII Bomber Command. The devastation was only duplicated in the raid that followed on Schweinfurt.

To weaken the Luftwaffenfighter force and secure the necessary air supremacy for the accomplishment of Operation Overlord, the American campaign goal for the daylight bombing sorties deep into Germany in 1943 was to do so. Because the Germans were successful in achieving their own goal of destroying so many Eighth Air Force bombers, the Americans were unable to complete their campaign objective by the middle of October 1943.

The North American P-51B Mustang was the actual answer to this problem. In reality, the long-range P-51B not only reduced bomber losses but also soon established air superiority over Europe, which helped pave the way for D-Day in numerous ways.

Schweinfurt-Regensburg 1943 is published by Osprey Publishing and is available to order here.

Photo by Robert Taylor via Aces-High.com, U.S. Army Air Force, and Rama via Wikipedia