The hottest ‘battlefield’ of the Cold War

Germany was the most heated “battlefield” of the Cold War, remaining divided for decades between the late 1940s and the early 1990s. According to Kevin Wright’s account in his book Danger Zone, the western portion of the region was littered with numerous significant military facilities belonging to both the reconstituted national armed forces and NATO allies, primarily the United States, Great Britain, and France. Even more so, the Armed Forces of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) controlled one-third of East Germany, which was home to numerous major air and ground units.

Three Aerial Corridors

The only means of communication between the German Democratic Republic (GDR)’s central city of West Berlin and its three occupation zones—controlled by the United States, Great Britain, and France—and the outside world were tightly controlled railways, waterways, and autobahns. Three Aerial Corridors, however, linked it to West Germany in the air. Several intelligence services from the US, Great Britain, and France took use of this feature to conduct covert operations along these Corridors, far away from high-profile intelligence-gathering operations such as those carried out by Lockheed U-2s.

These operations, which were mostly carried out by liaison or transport aircraft that had undergone a variety of clandestine modifications, frequently placed their crews in the middle of what NATO considered to be the “danger zone”—the airspace over some of the most sensitive Soviet military installations.

USAF RB-66 shot down

Up until the early 1960s, there were frequent navigational errors—both intentional and inadvertent—along the Inner German Border (IGB), with NATO aircraft occasionally straying into GDR airspace.

Mar. 10, 1964: Near Gardelegen in East Germany, near the Letzlinger Heide training area, a USAF RB-66 electronic reconnaissance aircraft from the 19th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron based at Toul-Rosières in France was shot down. The flight is described as a local training flight in the 1964 Annual Report of the United States Military Liaison Mission (USMLM). It happened during a major exercise being conducted by the Soviets in the area where it was lost.

Some narratives have tried to depict it as a botched attempt to obtain information on a significant Soviet exercise that was taking place on at the time on the training area. The least likely of all is the facts that claim the RB-66 was operating inside one of the Corridors, despite the fact that combat aircraft are not allowed to use them and that previous flight plans must be filed with the Berlin Air Safety Center (BASC).

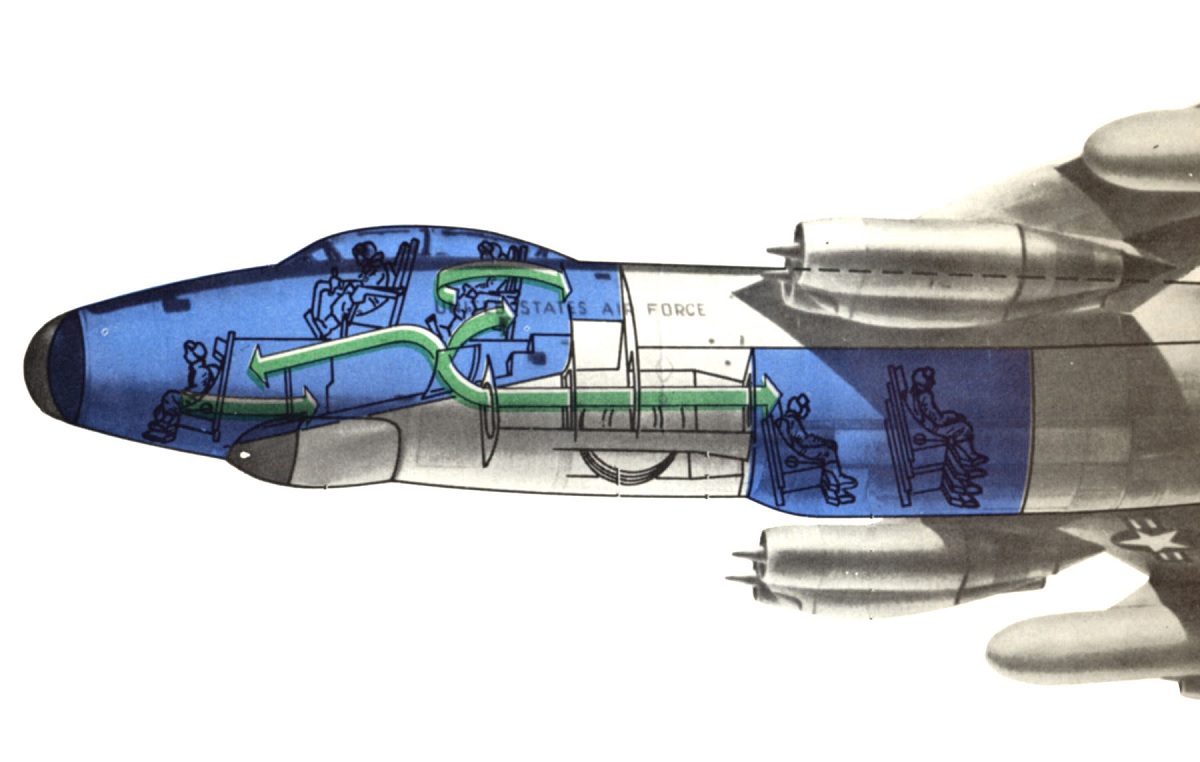

USAF RB-66 shot down by Soviet MiG-19s

When the Soviets discovered the RB-66’s intrusion, they had two Wittstock-based, 33 Istrebitel nyy Aviastionyy Polk (IAP, Fighter Aviation Regiment) MiG-19s on Combat Air Patrol (CAP) in their Northern Sector. The Quick Reaction Alert (QRA) flight from Zerbst launched two more MiG-19s, and they managed to intercept the RB-66 before the Wittstock aircraft did. Kapitan FM Zinoviev was ordered to engage the US aircraft as it turned westward and brought it down with a salvo of four S-5 unguided rockets followed by canon fire.

According to the 1964 Allied Military Liaison Mission (AMLM) annual report, the RB-66 vanished from radar screens around one hour after taking off and entered the German-Soviet Zone near Gardelegen, northeast of Helmstedt. In a matter of hours, USMLM teams were placed on alert and quickly set out to locate the aircraft and its crew. By then, they believed the three crew members had managed to parachute from the doomed aircraft. Though none of the three USMLM tour vehicles were allowed access, they were able to approach the site.

A ‘provocation’ flight

First Lieutenant Welch, one of the crew, was treated at a Soviet military hospital in Magdeburg after suffering a broken leg. He was returned to US custody on Mar. 21 with the pilot Captain David Holland and Captain Melvin Kessler following on Mar. 27, 1964. Subsequently, the USAF expended significant energy to prove that the misplacement of the RB-66 was due to a malfunction with its compass. While the Soviets maintained that the flight was a “provocation” intended to test their air defenses, the US has always stuck to the explanation of navigational error.

The French account

Another account of the incident is provided by the French. At the time, they had an N-2501 Noratlas “Gabriel V” that was operating along the Southern Corridor, and they had an active listening post at Berlin-Tegel. Between them, they recorded the RB-66 flying towards the IGB and then being downed by the MiGs. It implies that the RB-66 was operating close to the Central Corridor’s entrance, where they thought it was trying to locate a new Soviet radar. The ground station and the Gabriel V concurrently translated and recorded the intercepted radio exchanges, allowing them to triangulate the position of the RB-66.

Danger Zone is published by Helion & Company and is available to order here.

Photo by U.S. Air Force