The ground personnel at the base of the Yugoslav Air Force in Cerklje panicked as Yugoslav planes flew over it; they were not even aware that Thunderjets were used by their country’s air force, thus they assumed the F-84s belonged to the Italian Air Force

The Free Territory of Trieste was a political entity in the present-day Italian city of Trieste, located on the relatively short common borders between Italy and Yugoslavia. De facto, the area was divided between Yugoslavia, the new socialist federation in the western Balkans, and the western allies (US, UK, and Italy), despite the fact that it was technically a political entity founded as a result of the instability brought to Europe at the end of World War II.

About ten years after the conclusion of the war, the Trieste issue was still unresolved, and new tensions had developed between Italians and Yugoslavs. The US provided both sides with weapons under the Mutual Defense Assistance Program just before the crisis’s peak. Notwithstanding the fact that the conflict thankfully never materialized, it raised an intriguing question: Given that both nations fielded the F-84G Thunderjet jet fighter, how would the air conflict in this hypothetical conflict have played out?

Since the end of World War II, both Italy and Yugoslavia had an interest in the Trieste area. The territory was taken on May 1, 1945, by Slovenian partisan forces following a battle between German and Tito’s Yugoslav forces, despite the city itself and the surrounding territory having a far greater Italian population than Yugoslav (Slovenian and Croatian, to be more precise).

The city would not be a part of either Italy or Yugoslavia, according to the agreement the British-American forces, who were approaching from the west, had made with that country. The Free Territory of Trieste, which included Trieste and its surroundings, was split into two zones: Zone A (governed by The Allied Military Government) and Zone B. (administered by Yugoslav officials). Yet, both Italy and Yugoslavia were aware of the significance of this port in the northeastern Adriatic. Hence, the conflicts and disagreements over the Territory’s destiny started in the fall of 1953.

Foreign assistance was used to purchase the first post-war aircraft for both Italy and Yugoslavia. The US and the UK were Italy’s two primary suppliers. The resurrected Italian Air Force originally got ex-USAAF Mustangs and Thunderbolts, then British de Havilland Vampires, American F-86D Sabres, and American F-84G Thunderjets, the service’s first jets. The foundation of the country’s air force was built on aircraft. In May 1952, Italy received its first Thunderjet plane.

The Italian Air Force divided its F-84Gs into three Air Brigades (equivalent to the US Air Force’s squadrons) at the start of the hypothetical conflict: Verona-Villafranca (5 Aerobrigata; about 230 kilometers from Trieste), Ghedi-Montichiari (6 Aerobrigata; about 260 kilometers from Trieste), and Aviano (51 Aerobrigata; just around 100 km to Trieste). Together, the three Air Brigades were a part of the 56th Tactical Air Force, a group of about 180 F-84G aircraft stationed near Vicenza and within striking distance of Trieste. Overall, the Italian Air Force had 254 F-84Gs.

Although the most prevalent fighter type was the Yugoslav Ikarus S-49C, Yugoslavia constructed its post-war air force on foreign aircraft, similar to how Italy did. During the Mutual Defense Assistance Program, Yugoslavia was able to acquire American Thunderbolts and British Mosquitoes, followed by ex-USAF Sabre, Thunderjet, and T-33 aircraft. Yugoslavia’s air force received its first F-84G aircraft on June 9, 1953.

Up until October of that year, the remaining aircraft were being delivered in various pieces. The F-84G jet fighters in the Yugoslav Air Force’s fleet were less effective both in theory and in practice (F-86D Sabres were not yet prepared for use during the crisis). There were only 54 Thunderjets in operation at the time of the crisis, and they were all stationed in Batajnica (near the capital Belgrade, around 525 km to Trieste, serving under the 117th and 204th Aviation Regiment).

The large distance of the main base didn’t seem to be a significant disadvantage for the socialist air force, given that the F-84G’s combat range was approximately 1’600 km (with a ferry range of 3’200 km) and that, if necessary, the Yugoslav Thunderjets could use Zagreb-Pleso air base in Croatia (179 km to Trieste).

Nonetheless, the unit’s headquarters’ position was a major drawback in a prolonged fight where more sorties would be required to be flown. Despite the fact that 14 Thunderjets were sent to Zagreb-Pleso in November, their number would be insignificant when compared to the approximately 180 Thunderjets owned by the Italian Air Force. In the event that the conflict with Italy escalated, a detachment from the Yugoslav Air Force was also sent out to identify suitable sections of the Belgrade-Zagreb motorway that could be employed for the F-84G landings.

The Yugoslav Air Force’s entire staff’s lack of preparation was best demonstrated in one specific event. The Thunderjets from Zagreb-Pleso conducted a number of “show-off” sorties over Slovenia in addition to flying over the Cerklje base of the Yugoslav Air Force (equipped with Il-2s and F-47D). The ground staff of the air force panicked when the jets flew over the air base since they were not even aware that Thunderjets were used by their country’s air force, so they assumed that the F-84s belonged to the Italian Air Force.

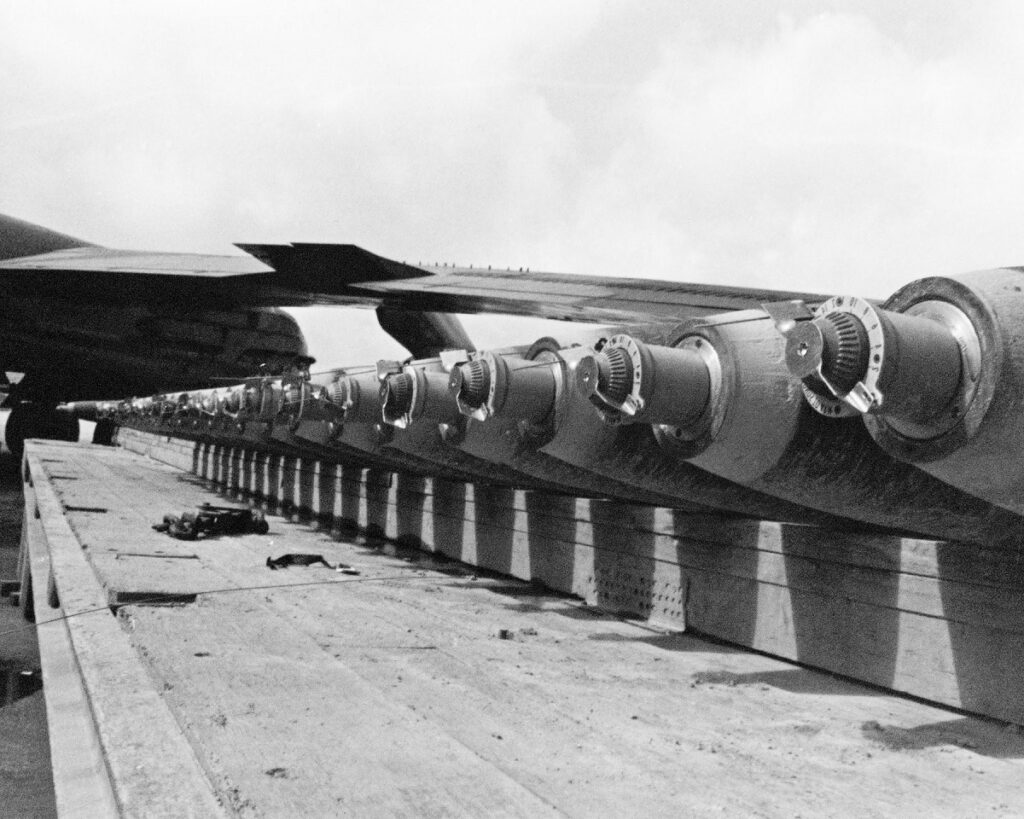

The Yugoslav Air Force’s fleet of Thunderjets faced additional challenges due to the pilots’ gradual adaptation to the new jets. A few Thunderjets pilots practiced dropping cement bombs and conducting gunnery drills during the crisis. After 14 F-84G aircraft and their pilots arrived at Zagreb-Pleso, gunnery exercises proceeded using aerial targets being pulled by F-47D aircraft, and the close-air-support exercise progressed to employing HVAR 5-in unguided rockets against ground targets. One of the Yugoslav Thunderjet pilots, Predrag Vulić, remembered that “… we had the airplanes with radar and gyroscope sights. No one among the pilots didn’t know how to use the sight. We also had minor knowledge in firing maneuvers too.”

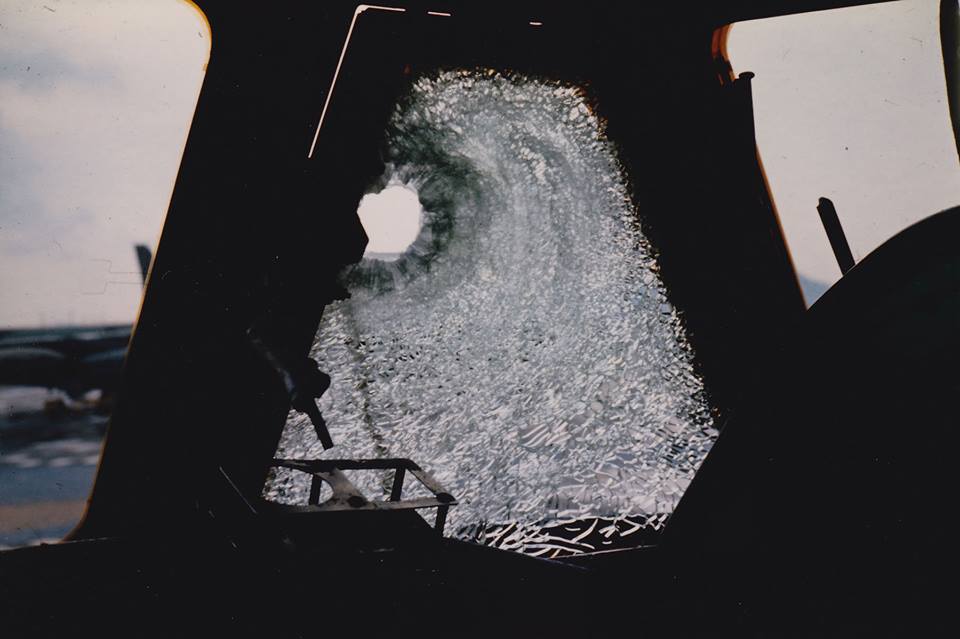

On the verge of a crisis, the Yugoslav Air Force conducted multiple reconnaissance flights over Italian territory using de Havilland Mosquitos, with the Italian air defense noting seven sorties. The Italian side also conducted reconnaissance flights over Yugoslavia; 23 Italian flights were recorded, but no additional information regarding the aircraft used in those violations could be found, and it was likely that the Thunderjets were not employed. Two Yugoslav F-84Gs from Zagreb-Pleso took off on one occasion of an Italian violation in order to confirm the visual sight and to intercept an Italian aircraft that was alleged to be over Yugoslavian territory on November 26.

The Italian aircraft had already departed when the Yugoslav jets finally took off after nine minutes. The Yugoslavian pilots would probably not even respond unless they were “fired at first,” in the event that an Italian aircraft was spotted. This rule of engagement was adopted as a result of the 1946 Yugoslavian downing of a US Army Air Force C-47 over Slovenia, which led to heightened tension between the west and Yugoslavia.

Duel: Italian vs Yugoslav F-84Gs

Italy, unlike Yugoslavia, had no problems with the Thunderjets’ operational service. Italian pilots had more time to learn to fly the first generation of jet aircraft than their Yugoslav counterparts since Italy received its first jets a year before Yugoslavia. The training itself, which was once again of considerably greater quality in Italy, was the most crucial factor. Italy was working with its western partners as one of the NATO members.

Yugoslavia, which after Tito and Stalin’s break traveled on its own “lonely” path, was made to undergo de facto independent training for the new aircraft. Although American personnel had a considerable impact on the training of Yugoslav pilots, the Italians’ level of quality was never reached by the Yugoslav Air Force.

Better airstrips and air bases could be employed to support the forthcoming aircraft’s operational needs in northern Italy. In contrast to Yugoslavia, Mussolini’s government spent a lot of time and money before World War II modernizing both the air force and its air bases. Even though Yugoslavia had an air force prior to the Second World War, the air bases were not prepared to house the jet-powered modern aircraft.

After the war, Yugoslavia was left with just one modern air base that could accommodate such aircraft, the Batajnica air base near Belgrade. When the first F-84Gs began to take off from it, even the Zagreb-Pleso air base, which served as an air base for 14 Thunderjets, had to be expanded.

The Thunderjets would have likely only been employed by Italy if a conflict between Italy and Yugoslavia had started. Three air sites less than 300 km from Trieste, where many of its F-84Gs may have operated, would have required a large number of sorties to be flown in the event of a conflict. Yugoslavia, on the other hand, had only one-quarter of the Thunderjets compared to Italy.

The crucial point to remember is that only 14 of them, which were flown by experienced pilots, were qualified to conduct combat operations. While Batajnica was more than 500 kilometers from the hypothetical conflict area, Croatia had the only air base that was adequate for the mission. The Yugoslav Air Force was reluctant to employ its expensive jet aircraft in a direct conflict until all of its fighter jets, including the Thunderjets and Sabres, were prepared.

But again, the important logistical topic pops out. Probably the only aircraft, which Yugoslavia would use against Italian Air Force in the dogfights would be the piston-powered Ikarus S-49. Even though Yugoslavia operated Bf-109Gs and Spitfires after the end of the war, the potential use of these world war two aircraft against Italian jets was unlikely.

Yet, the crucial logistical issue came up once more. Very likely the only aircraft that Yugoslavia would employ in dogfights with the Italian Air Force is the piston-powered Ikarus S-49. Even though Yugoslavia continued to fly Spitfires and Bf-109Gs after the war, it seemed improbable that they would be used to take on Italian jets.

Fortunately, the problem was resolved by partitioning the region between Italy and Yugoslavia, preventing any military action between the two nations. The rise in political and military tension between Italy and Yugoslavia in the early 1950s was comparable to the first Berlin Crisis and the rise in tension between the western allies and the Soviet Union, despite appearances to the contrary. With this quick analysis, we can say that the Italian Thunderjets would have ruled the skies over Trieste in the hypothetical battle scenario if both sides would have been equipped with F-84Gs as their first jet aircraft.

Sources:

- DIMITRIJEVIĆ B., 2003. Jugoslavija i NATO (Yugoslavia and NATO). Beograd : Tricontinental, ISBN 86-84269-02-0

- DIMITRIJEVIĆ B., 2019. The Trieste Crisis 1953: The first cold war confrontation in Europe. Helion & Company Limited, ISBN 978-1-912866-34-2

- RADIĆ A., 2020. The Yugoslav Air Force: In the battles for Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1991-1992 Volume 1. Helion & Company Limited, ISBN 978-1-912866-35-9