On October 25, 1944, at 1053 in the morning, an A6M5 Zeke purposefully struck the USS St. Lo (CVE-63), a survivor of the Battle off Samar

The U.S. Navy achieved such resounding triumphs in October 1944 that, had it come up against a different enemy, the war would have been over. However, as Thomas McKelvey Cleaver tells in his book Tidal Wave, the US Navy confronted a terrible new enemy tactic near the close of the Battle of Leyte Gulf, just when it appeared that they had won.

The defeat of the Imperial Japanese Navy, which at this point no longer posed a credible threat, was the objective for which the U.S. Navy had been established over the preceding 20 years by 1000 hours on the morning of October 25, 1944. Along with the carriers Chitose and Zuiho, Zuikaku, the final survivor of the six aircraft carriers that had assaulted Pearl Harbor 34 months previously, lay on the bottom 100 miles north of Cape Engano. One of the two biggest battleships ever built, the Musashi, was sunk in the Sibuyan Sea.

In Surigao Strait, the battleships Fuso and Yamashiro had been destroyed. After a terrible battle off the island of Samar, Admiral Kurita’s Center Force was in retreat through San Bernardino Strait. No other Japanese capital ship would seek engagement with the US fleet for the remainder of the war, with the exception of the battleship Yamato’s one-way assignment in the Okinawa campaign six months later. The victory that had been anticipated over the last 20 years had been realized. The outcome of Leyte Gulf was described by British historian J. F. C. Fuller in his book The Decisive Battles of the Western World as follows: “The Japanese fleet had [effectively] ceased to exist, and, except by land-based aircraft, their opponents had won undisputed command of the sea.”

The Philippines’ defeat was catastrophic for Japan. The Imperial Japanese Navy has lost more ships and personnel in battle than at any time in its history. The defeat meant the inevitable loss of the Philippines. This in turn meant that Japan would be completely cut off from the Southeast Asian nations that it had invaded in 1942, which had provided her with resources essential for survival, most notably the oil needed for hardships and the fuel for her airplanes, as well as food for the Japanese people.

Admiral Yonai, the Navy Minister, said when interviewed after the war that he realized the defeat at Leyte “was tantamount to the loss of the Philippines.” As for the larger significance of the battle, he said,n“I felt that it was the end.”

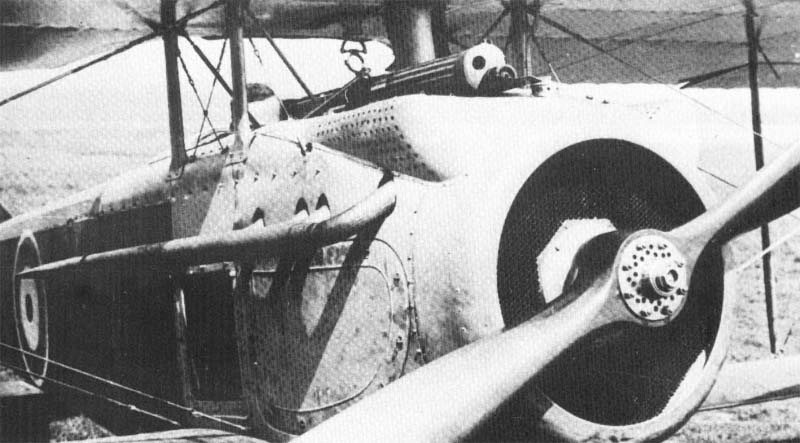

The Imperial Japanese Naval Air Force’s 201st Air Group’s Shikishima Unit discovered the Task Unit 77.4.3, or “Taffy-3,” carriers north of Samar Island at 1047 hours, 47 minutes after Admiral Kurita pulled his force back to San Bernardino Strait, thus altering the course of the Pacific Naval War. An A6M5 Zeke purposefully struck USS St. Lo (CVE-63), a Battle of Samar survivor, at 1053 hours. The kamikaze had arrived.

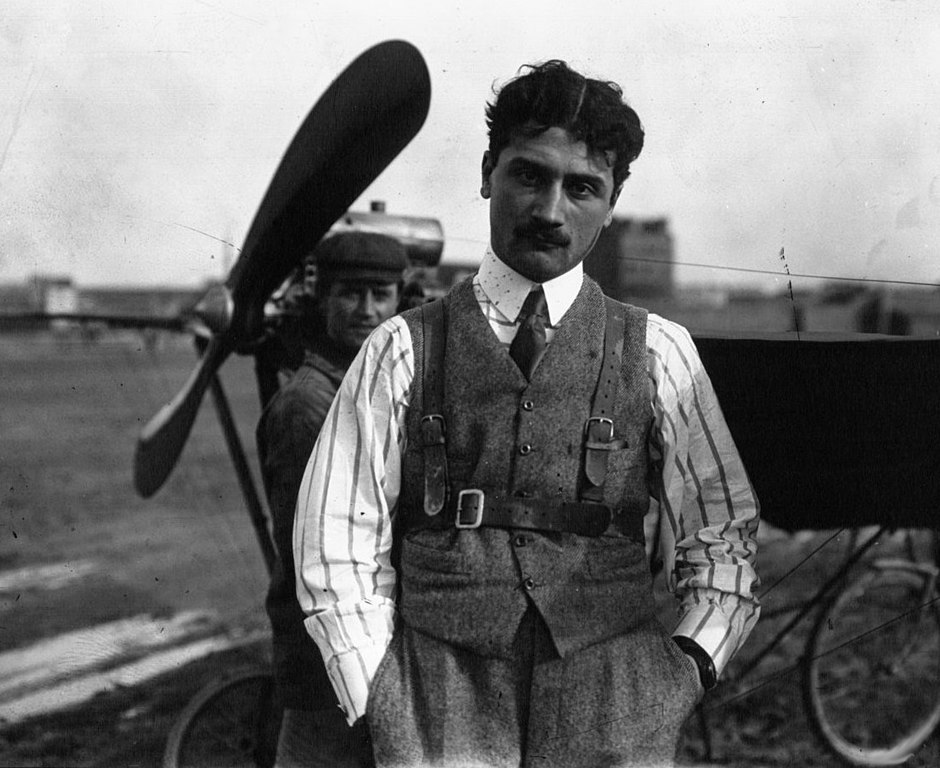

The Shikishima unit flew its first mission on October 24, 1944, with Lieutenant Yukion Seki leading four attackers and Imperial Japanese Naval Air Force leading acenHiroyoshi Nishizawa leading four escorts. The 201st moved from Mabalacat to Cebu in the central Philippines to put themselves closer to their targets. They returned to base with very little fuel because of the poor weather and dense clouds that day, failing to locate any targets.

On the morning of October 25, Seki led four old A6M2s that were each carrying a 250 kg bomb while Nishizawa led four A6M5 Zeke escorts. The Zekes were intercepted by Hellcat defenders, and in the fight that developed, Nishizawa claimed two of the Hellcats as victories 86 and 87. The attackers and the escorts split apart. A single attacker dove at Kitkun Bay (CVE-71) in an effort to damage her bridge, but it blew up as it contacted the port catwalk and cartwheeled into the sea. Fanshaw Bay (CVE-70) was attacked by two more, but they were both destroyed by antiaircraft fire. The last two took place in White Plains (CVE-66). While the other abandoned the effort and turned toward St. Lo under heavy fire and smoke, the first was hit and shot down by the antiaircraft fire.

Lieutenant Seki had found his target.

The Zeke pulled up at the last moment to correct the dive and the airplane hit the center of the flight deck. The 250-kilogram bomb detonated while numerous aircraft were being refueled and rearmed on the port side of the hangar deck. The torpedo and bomb magazine exploded after six subsequent explosions, which were preceded by a brief gasoline fire. St. Lo sank 30 minutes later, in flames. An 889-person crew had 113 dead or missing, while 30 survivors eventually perished from their injuries. The destroyer Heermann and its escorting John C. Butler, Raymond, and Dennis pulled the 434 survivors from the ocean.

It was the sign of the impending storm known as the kamikaze, so named after the typhoon winds that sank Kublai Khan’s invading fleet in 1274. 3,860 Japanese pilots would attack Navy ships during the course of the final ten months of the Pacific War; 733 of them would succeed in hitting their mark. In a letter to the Joint Chiefs of Staff in June 1945, Admiral Nimitz made it clear that the Navy could not support an invasion of Japan in the face of this threat.

The human wind of the 20th century “divine wind” may have prevented or at least significantly delayed the planned American invasion of Japan while the Soviet Union invaded the nation from the north, if not for the Soviet invasion of Manchuria and the use of two atomic bombs that prompted the Japanese decision to surrender.

Tidal Wave is published by Osprey Publishing and is available to order here.