While the SR-71 was operational, several pilots flew the Blackbird faster than the official record but not during sanctioned record attempts

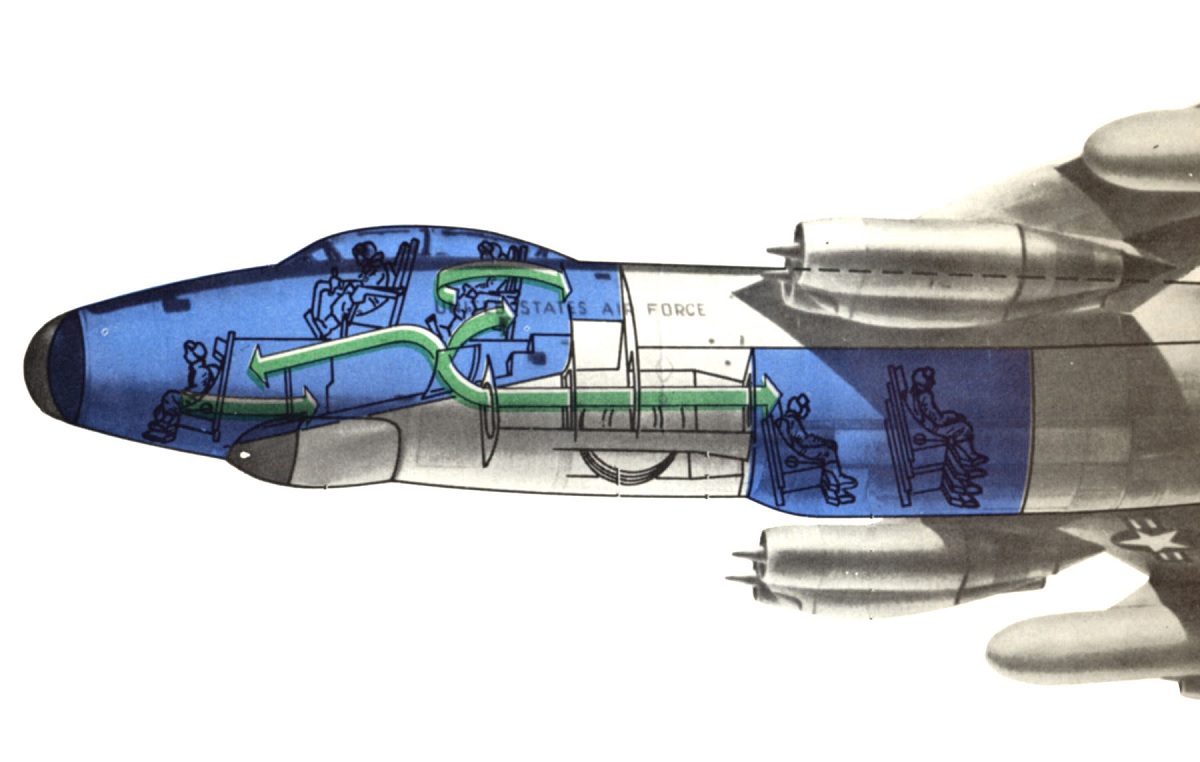

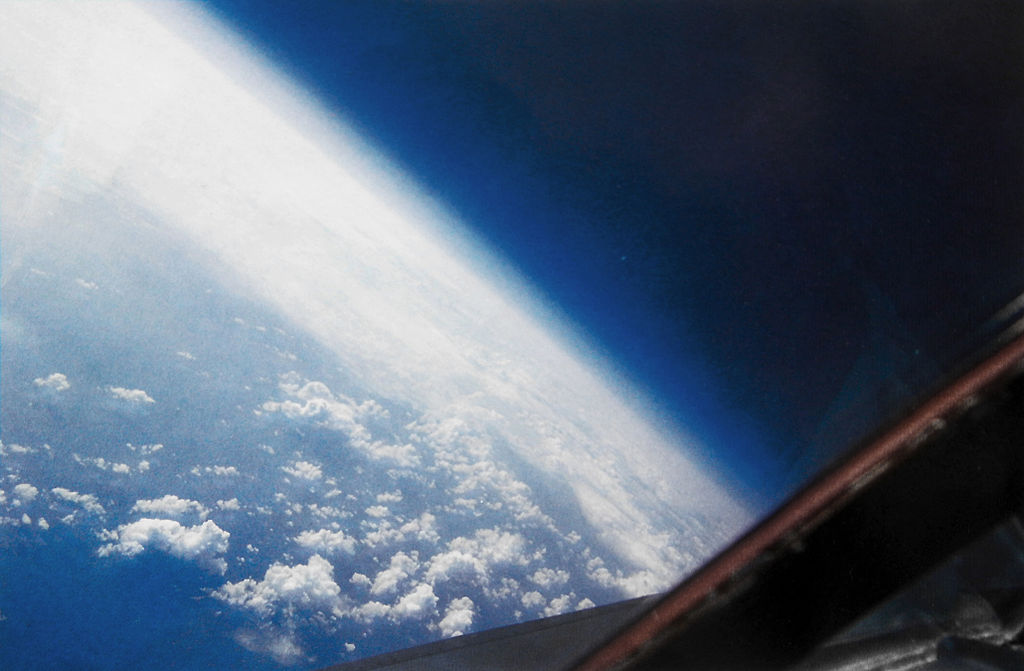

The Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird Mach 3 strategic reconnaissance aircraft maintained its position as the world’s fastest and highest-flying operational aircraft for approximately 24 years. It could survey 100,000 square miles of the Earth’s surface per hour from an altitude of 80,000 feet.

It is therefore not surprising that the aircraft has consistently broken records for both speed and altitude due to its astounding flight qualities.

Three US Air Force (USAF) aircrews broke three unbreakable world aviation records in two days in July 1976 while flying the Mach 3+ SR-71 high-altitude surveillance aircraft. Those marks remain intact, as Jeff Rhodes explains in his Absolute Blackbirds article in Code One Magazine. Absolute Speed is still regarded as the record for the fastest airborne speed attained by humans.

Aviation records have been kept since officials from eight nations, including the United States, gathered in Paris in October 1905 to create the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, or FAI. Later, the FAI evolved into the organization that controls official spacecraft as well as planes for use in aviation sports. The FAI is represented in the United States by the National Aeronautic Association or NAA.

The first records that were acknowledged by the FAI were established a year after it was founded. On September 14, 1906, near Bagatelle, France, Brazilian Alberto Santos-Dumont piloted his box-kite-like aircraft, known as the 14-bis, over a very constrained course with a radius of just 25.8 feet. Santos-Dumont increased the closed-course distance record that November to 733 feet and established the first officially acknowledged speed record of 25.6 mph.

To commemorate the US Bicentennial, USAF authorities intended to fly the SR-71 on a special, noteworthy mission seventy years later. First considered but ultimately rejected was a speed flight around the world. Then, according to Al Joersz, who was in charge of SR-71 standardization and evaluation for the 9th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing (SRW) at Beale AFB in northern California, where the now-retired SR-71s were based, in 1976 as an Air Force captain, “we looked at what could be accomplished on a typical training sortie.”

Unit officials looked through the record book and found three absolute records that their Blackbirds could break: speed over a closed circuit, altitude in horizontal flight, and speed over a straight course of 15 to 25 kilometers.

“Jim Sullivan, our squadron operations officer and the pilot who set the New York-to-London speed record in the SR-71 in 1974, came to me and told me I was going to set the absolute speed record,” noted Joersz. “We had several crews deployed, so the most experienced crews we had on hand were picked.” Because of the intense crew coordination required, SR-71s were always flown by dedicated two-man crews.

Beale’s wing mission planning organization coordinated the flights, working with both the FAA and NAA. “We flew the mission a couple of times in the simulator,” recalled Joersz. “That sim was all analog—our moving map consisted of a scrolling paper map—but it did prepare crews for flights.”

Although the scheduled Fourth of July flight date was postponed due to a lack of approvals, everything was prepared by month’s end. The Air Force Flight Test Center at Edwards AFB in southern California is where the speed and altitude measurements were made, though the flights started and concluded at Beale.

To break the Speed Over a Closed Course record, Maj. Pat Bledsoe, the wing chief of standardization/evaluation (the wing then, as now, also handled the U-2 reconnaissance aircraft), and Maj. John Fuller, his reconnaissance systems officer, took off first on July 27. A huge circle, similar to the one used during Santos-Dumont, marked the limits of the 1,000 km (621 miles) closed course. In order to essentially circle the area, Bledsoe flew Blackbird 958, Air Force serial number 61-7958, on six straight-line paths, entering and exiting the track at the same location. He comfortably beat Mikhail Komarov’s record of 1,852.61 mph set in 1967 in the E-266, a heavily modified Soviet MiG-25, by finishing the course at 2,092.29 mph.

Unfortunately, scattered clouds over Edwards later that day prevented Joersz and his RSO, Maj. George Morgan, from setting the Absolute Speed record, and Capt. Bob Helt and Capt. Larry Elliott from setting the Altitude in the Horizontal Flight record. “For the Absolute Speed record, the rules say that the aircraft’s altitude can’t vary by more than 150 feet from the assigned altitude over the course,” noted Joersz. “Once the clouds came in, altitude couldn’t be measured accurately from the ground. So we flew again the next day.”

Helt and Elliott attempted to break the sustained altitude record on July 28 but encountered an issue with the assigned SR-71, serial number 61-7963. The key to hitting this mark was to accelerate swiftly while maintaining height. On November 13, 1908, Wilbur Wright achieved the first altitude record in history, rising eighty-two feet. The previous record, which was set in May 1965 by USAF Col. R. L. Stevens in a YF-12, one of the SR-71’s predecessors, was 80,257 feet. The record set by Helt and Elliott was 85,069 feet, greatly breaking that record by more than three orders of magnitude.

Joersz and Morgan, piloting Blackbird 958, had to cross the electronic timing gate, fly the 25-kilometer circuit, cross a second timing gate, turn around, and repeat the course from the opposite end to negate the impact of winds in order to break the Absolute Speed record. The crew had an unstart—Blackbird-speak for an engine shutdown—just after crossing the timing gate on the second leg while flying at a speed of Mach 3.3.

“On an unstart, the aircraft yaws and the nose pitches up,” Joersz noted. “There is a five-step checklist to get the engine relit. I knew I had to keep the nose down to stay in the 150-foot box, so that’s what I concentrated on. By the time we’d gone through the checklist, we’d already passed the second gate. Still, we exited the gate at Mach 3.2.”

The two legs’ combined average speed of 2,193.16 mph broke Stevens’ previous record of 2,070.101 mph set with the YF-12. Several pilots flew the Blackbird faster than the official record when the SR-71 was in service, but not during authorized record attempts.

“The records weren’t a big deal at the time,” said Joersz. “I was just happy to fly the aircraft. I flew an instructional sortie the next day.” The SR-71 speed and altitude marks were quickly certified as world records. The three crews went to the Paris Air Show the following year to receive commemorative medallions from the FAI.

The FAI decreased the number of absolute records in 2006 to the best-ever performance with no restrictions, including distance, speed, altitude, and maximum payload. The records established by Bledsoe and Helt are now referred to as Class C and C-1, Landplane records, which means they are still valid but have been relocated from the first page of the official record book.

“One of our maintainers came up to me after the record flight and said, ‘This is the flight people will remember. It’ll last a long time,’ ” recalled Joersz, who rose to the rank of major general and later had a twelve-year career in advanced development with Lockheed Martin before retiring in 2010. “After our flights, the emphasis in aerospace as a whole shifted from speed and altitude to maneuverability and stealth.”

Photo by Lockheed Martin