“The guys at Tonopah had a sense of humor after all, for the silhouette of an F-117 had been stenciled on each side of our tail fin,” Squadron Leader Wally Grout, former RAF Tornado navigator

The following article contains excerpts from Squadron Leader Wally Grout’s story titled Still Learning After All Those Years which appears in Ian Hall’s book Tornado Boys.

So there I was, just approaching my 40th birthday and all fired up to participate in my first Red Flag exercise in the States. After just four missions, my pilot and I were tasked as the lead crew for the package on 9 April 1990. I had spent my earlier years on the mighty Vulcan, having been posted from nav school as a navigator radar, and was lucky enough to be one of the first to cross over to the Tornado GR1 in January 1982. Red Flag was, at that time, a distant dream.

I was now on my second Tornado tour; I had 440 hours on type and, together with my pilot, was now to lead the planning and execution of a typically complex mission into the heart of Red Flag territory. I had come a long way.

Our mission was to penetrate the defenses and drop two inert 1,000 lb bombs into an airfield target using a loft maneuver. All Red Flag aircraft are fitted with telemetry pods and, much like Formula One racing cars, can transmit information back to the HQ so that supervisors and spectators can watch the progress of the ‘war’ on a big screen in real time.

We were airborne on time and proceeded to Caliente, our holding point for entry into the Red Flag area. Whilst orbiting, checking maps, timings, and aircraft systems we detected a fault; fuel was not feeding on the wings into the fuselage tanks. This problem was not insignificant and, although the checklist gave advice and possible solutions, the fault could lead to serious fuel imbalance and possible mission abort.

We were approximately three minutes from our push time; just sufficient to go through the initial actions from the checklist. But we had no time to see if the problem was cured.

We completed the pre-target checks, found the initial point, and performed the attack. Job did, bombs on target, time to recover. Once settled we did a routine op check. As we covered ‘fuel’ our heart rates increased. We had not cured the fuel transfer problem; both of us having been fully tied up with the mission, we’d not double-checked. It was now clear that we didn’t have enough usable fuel to get back to Nellis, even in a straight line.

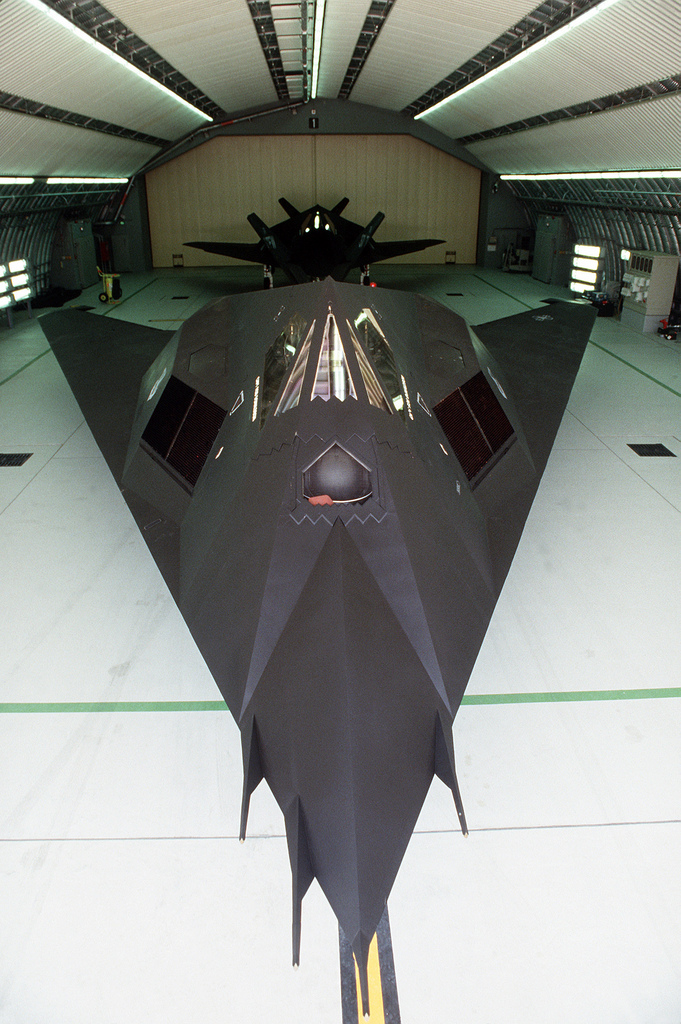

The next few minutes seemed to last forever. From the map, Tonopah was our nearest diversion, and I gave my pilot the relevant track information. Simultaneously, we transmitted to Red Flag control that we were diverting with an emergency. In fact, with the telemetry pod ‘big brother’ probably knew already — but that call seemed to set the cat amongst the pigeons. Tonopah at that time was home to the USAF / Lockheed ‘skunk works’, a highly secret development site for the stealth bomber program. We all knew about the F-117 but, as yet, it hadn’t been officially cleared for public consumption.

You can now imagine the reaction over the radio. “Why do you need to go there? You cannot get there. What exactly is wrong with your aircraft? Why can’t you go to Indian Springs?” (a less sensitive diversion airfield). We even had our detachment commander quizzing us. All the time fuel was reducing and we were getting closer to Tonopah. Between us, we convinced all and sundry that our only alternative to Tonopah was an ejection over the desert. That shut them up, and we now got a period of relative quiet on the radio while we concentrated on getting our aircraft safely on the ground. We hadn’t really thought about what would happen after that.

After touching down we were instructed to clear the runway, stop, and shut down. We complied, made the seats safe, and raised the canopy.

What happened next is the stuff that makes Hollywood great. Several vehicles formed up in front of the aircraft, including one full of armed soldiers. Steps were brought and we climbed out. A USAF major greeted us; he confiscated the film cassettes from the HUD and the data recorder, told us that the aircraft would be looked after, and escorted us under armed guard to the operations center. Good job that I didn’t on this occasion have the 35mm camera I usually carried with me or they really would have thought we were spying! He guided us to a windowless room with blank walls and minimal furniture. We sat down, wondering what would happen next. We both felt reasonably relaxed, apart from the armed guards — after all, we had saved the aircraft and felt justified in our actions.

The major then explained our predicament. Landing at a top-secret establishment in the USA is not an everyday occurrence and we were now going to be questioned — or, as it later turned out, interrogated. Our interlocutor asked all the standard questions: name; rank; squadron; nationality; why we landed at Tonopah. And some more personal: marital status; family background; and educational qualifications. All the while, two large military personnel armed with carbines stood by the door.

Having finished with his questions the major left the room. After a few minutes, another male entered the room, dressed casually in civilian clothing. No introduction, no name given, just more questions. It was almost a repeat of those we had already answered. However, erring on the side of, ‘let’s not make waves’, we both answered them.

He left and we sat chatting about our situation while the guards remained in the doorway. It was now time for my bladder to complain; a post-flight comfort call was needed. I told the guards I needed the `john’. The response took me by surprise; a guard would have to escort me — I assume to prevent me from running amok. He duly stood a few races behind me as I took relief. I was escorted back to the room and we waited some more.

I then recall a further interrogator asking the same questions and getting the same responses. The major returned to tell us that our aircraft was now confiscated and that we would be flown back to Nellis in one of theirs. We would be told when we could have ours back, and we would be the only crew allowed to return to pick it up. He left us to puzzle why.

Soon we heard the sound of aircraft taxiing. We asked a guard if the F-117s were flying this afternoon, to which he shrugged. I said, “I suppose you have to wait until the surveillance satellites are clear before you fly the 117?” His response was standard USAF: “I do not know what you are talking about, sir.” Further questions elicited similar responses. We gave up. More aircraft noise from outside; more flying tonight? It was getting late in the afternoon.

Eventually our ‘friendly’ major returned with news that, for operational reasons, we would not be flying back to Nellis but it would be a road trip instead. We asked if the operational reason was the fact they were flying the F-117. He gave a non-committal smile.

More waiting, but then we were told that transport was available and asked to get our kit together. The next move stunned us both; we black cloth bags put over our heads. We were led out of the room and outside; we could hear the sound of jets but thought it better not to ask more questions. We were helped into the rear seats of a vehicle. As the doors closed, our guards in the front seats had a few words for us to digest. “Do not remove your blindfolds, we are live-armed.” “OK,” we said; the understatement of the year.

We drove in silence for what seemed an age. The bags had not been tied under our chins and I made a conscious effort to get a handle on the direction of travel by looking down and using the shadows; it was now getting close to sunset and I estimated that we had been traveling west for the majority of the time. When we finally stopped and the guards told us to remove our blindfolds, I turned around and could just see a tiny speck in the distance, which I assumed was an F-117 in the circuit. We were at the main gate and the aircraft must have been about fifteen miles away. What a main street to an airfield!

For our journey back to Nellis we were given brown paper ‘sacks’ of sandwiches, chocolate, and fruit juice — courtesy of the Tonopah fire department dinner lady. That was about the only friendly gesture we’d had all afternoon, and boy was the food welcome.

The welcome at Nellis was cool but not hostile. It came as rather a surprise to the RAF commander that we would be told when we could have our jet back. We hadn’t serviced the aircraft, but NATO air forces regularly exercised on each other aircraft so we assumed our ‘hosts’ had a capability. Furthermore, strange as it may seem, there was an RAF pilot on an exchange tour on the F-117 at the time. Indeed, digressing slightly, during the Iraq War an ex-Tornado pilot took an active part in operations, flying an F-117. But did we think we had got away with it?

The next day a telephone message told us to get over to the other side of Nellis field, where a USAF Beechcraft was waiting to take us to Tonopah. We were met by a very young USAF pilot; we boarded, made ourselves comfortable while the crew gave us a quick safety brief, and off we went. The pilot wanted to know why and how we had gone to Tonopah, and also asked if we needed anything doing to our aircraft.

As we approached the field the pilot informed us that we would have to be airborne in less than forty minutes after arrival. He couldn’t say why, but he let on that there would be jets out for flying. We were not allowed to see them but, as we broke into the circuit, he hinted that if we looked out of the starboard window we would get an extremely good view of two ‘invisible’ aircraft. Shame that I’d left my camera behind!

He dropped us close to our aircraft and, once again, armed guards watched us; our friendly major was on hand to see us off, repeating that we had forty minutes to get airborne. As we did an inspection we noticed that the guys at Tonopah had a sense of humor after all, for the silhouette of a stealth fighter had been stenciled on each side of our tail fin. And in the cockpit, tucked under the windscreen, was a police parking ticket for illegal parking on US military soil. We had with us a couple of squadron prints, one for operations and one for the fire department. As we gave these to our major he presented us with a print of the F-117, even though it didn’t officially exist. The last time I had the chance to look, the print was still on the walls of the crew room at Marham.

That’s not quite the end of the story. Having debriefed the engineers about our fuel problem, they did their investigation and found that the transfer valve was indeed not working. Hurrah, at least we got that bit right. However, in hindsight, that well-known exact science, we should have monitored the fuel flow more closely and, if necessary, aborted the mission. But you know how it is — leading the pack, adrenaline rush, must complete the task, and all those other excuses for not giving up. All very well in peacetime to press on — but what about real war?

Update: Mike Crutch, author of the book CVW: US Navy Carrier Air Wing Aircraft 1975-2015, brought to our attention that “a RAF Phantom FGR.2 (F-4M in the US speak) diverted there also during a RED FLAG, arriving back at Nellis with a day glo F-117 sticker and legend DON’T ASK. The diversion took place on Nov. 9, 1989, and the aircraft was Phantom FGR.2 serial XV476 (coded ‘S’ with No.56 Squadron, based at RAF Wattisham, UK but was part of a mix of airframes from UK and RAF Germany units as crews changed during RED FLAG). The zap was applied to the port engine intake.” Unfortunately, we couldn’t find any photo of this aircraft with the F-117 Zap.

Photo by Crown Copyright via Ian Hall, U.S. Air Force, and Mike Freer – Touchdown-aviation via Wikipedia