Robbie Risner attempted to push 1st Lt. Joseph Logan’s F-86 toward Kimpo by having Logan turn off his engine and sticking his own Sabre’s nose into Logan’s tailpipe

Prior to “Pardo’s push” on March 10, 1967, there was a similar event.

Robbie Risner is renowned for his bravery throughout his 7.5 years of imprisonment and torture in North Vietnam. His eight confirmed victories as a jet ace in Korea are less well known.

On September 15, 1952, a chemical plant on the Yalu River close to the East China Sea was attacked by F-84 Thunderjet fighter-bombers, escorted by Risner’s F-86 Sabre aircraft. Risner’s flight passed over the Chinese MiG base at Antung Airfield while they were defending the bombers. Risner pursued one MiG along a dry riverbed and across low hills to an airbase 35 miles (56 km) inside China, fighting it at nearly supersonic speeds at ground level. After hitting the MiG multiple times, shooting off its canopy, and setting it on fire, Risner pursued it through the Communist airbase’s hangars before shooting it down into parked fighters.

During the return flight, anti-aircraft fire over Antung struck 1st Lt. Joseph Logan, Risner’s wingman, in his fuel tanks. Risner tried an unprecedented and untried maneuver, having Logan shut down his engine and stick his own jet’s nose into Logan’s tailpipe, in an attempt to push Logan’s aircraft and help him reach Kimpo. The object of the maneuver was to push Logan’s aircraft to the island of Cho Do off the North Korean coast, where the Air Force maintained a helicopter rescue detachment.

“A typical fighter pilot,” said Risner in a beautiful article by John L. Frisbee appeared in Air Force Magazine, “thinks less about risk than about his objective.”

Logan’s engine was nearly out of fuel when Risner ordered him to shut it down. The upper lip of his air intake was then carefully placed into Logan’s F-86’s tailpipe. “It stayed sort of locked there as long as we both maintained stable flight, but the turbulence created by Joe’s aircraft made stable flight for me very difficult. There was a point at which I was between the updraft and the downdraft. A change of a few inches ejected me either up or down,” Risner recalled.

The film of hydraulic fluid and jet fuel covering his windscreen and impairing his eyesight meant that every time Risner made contact again with the battered nose of his F-86 and Logan’s aircraft, there was a far greater chance of disaster. It seemed like trying to move a car at eighty kilometers per hour through dense fog on a corduroy road.

Risner’s F-86, piloted by Joe Logan, somehow nudged all the way to Cho Do while flying at 190 knots and high enough to avoid automatic weapons. Logan bailed out close to the island, ending up in the water close to the coast. However, Risner’s heroic attempt was unsuccessful. Logan was a skilled swimmer, but before rescue could reach him, he drowned after getting tangled in his chute lines. But the measure of a heroic act lies not in success. It lies in the doing.

Robbie Risner’s career in the Air Force after Korea was characterized by both moral and physical bravery, which culminated in his leadership of American POWs during those arduous years in Hanoi’s prisons. Generations of airmen to come would aim to reach the standards of bravery, devotion, and hard work he set for himself and brilliantly fulfilled throughout his time in uniform.

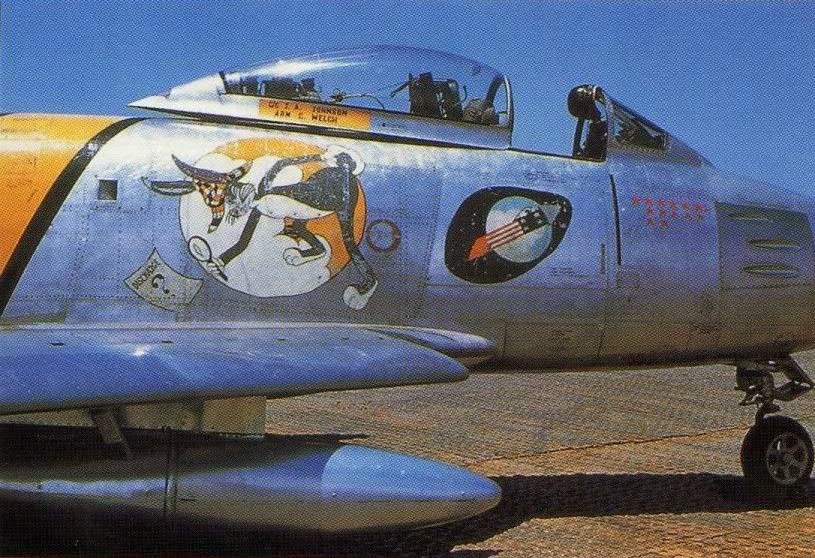

Photo by U.S. Air Force and DCS