“The two planes were so close I could see the Germans’ eyeballs, as big as eggs, as we peppered them,” Merritt Duane Francies, L-4H Grasshopper pilot.

By April 11, 1945, American tanks from the 5th Armored Division were advancing across central Germany in the direction of Berlin, with the 71st Armored Field Artillery Battalion taking the lead. The unit crossed the Weser river at Hamlin and continued to advance east while armed with M7 self-propelled 105mm howitzers and M4 Sherman tanks.

According to the battalion’s official history, Fire Mission: The Story of the 71st: “The old familiar tactics of bypassing heavy resistance by using secondary roads and passing through only small villages were put to use again.

“Sixty and 70-mile marches were standard operations during the passing of those lightning-fast days. The deeper we drove into the Reich the longer our supply lines were stretched and the more difficult the job of service battery became.”

And on Apr. 11: “That day German air activity increased over the column. All sizes and types either roared or limped past. Our ack-ack would pull off to the side of the road at the slightest pause.”

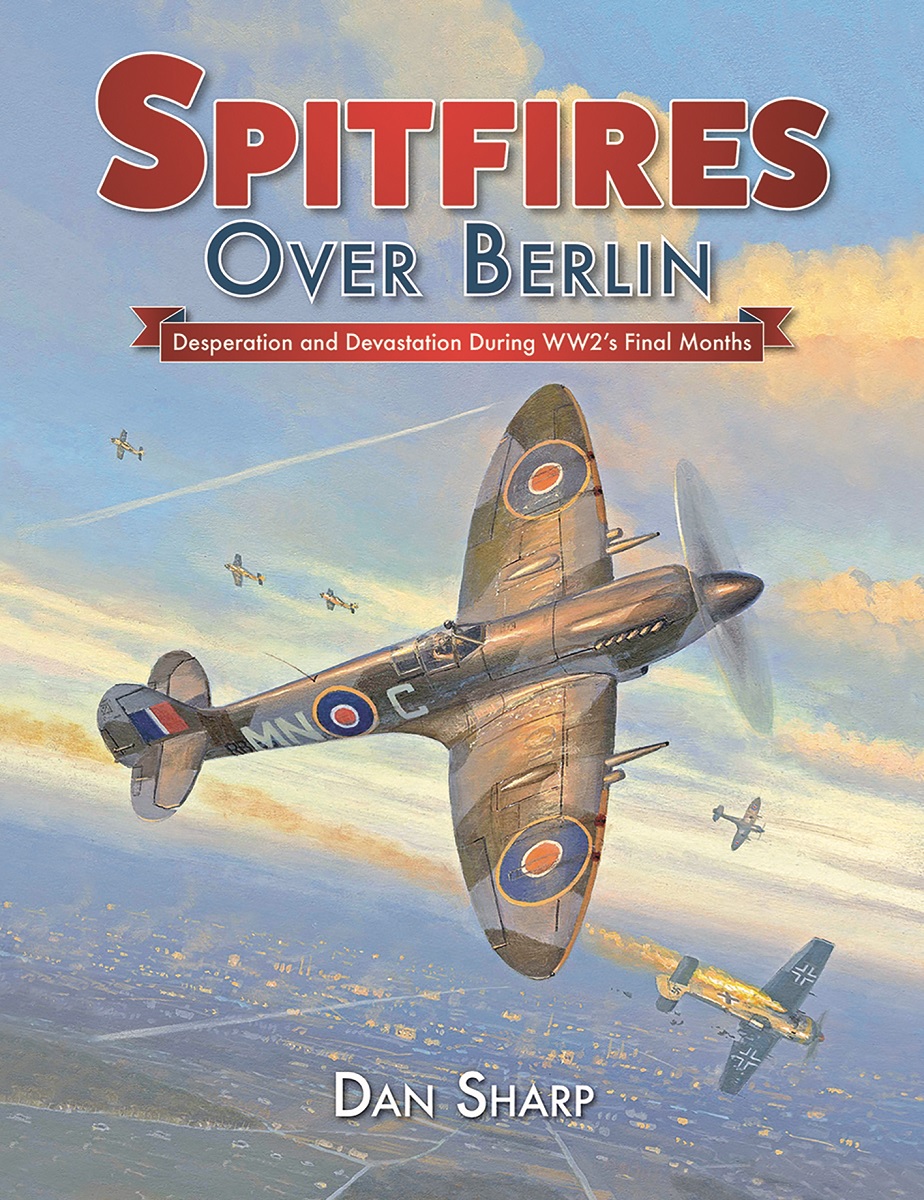

The 71st’s progress had been directed by spotter pilots flying ahead over the enemy territory since landing at Utah beach on July 28, 52 days after D-Day, as described by Dan Sharp in his book Spitfires Over Berlin. The spotters flew long hours in frequently hazardous weather while outfitted with tiny two-seat 65hp Piper L-4 Grasshoppers.

Merritt Duane Francies, a 24-year-old Grasshopper pilot from Wenatchee, Washington, was one of the most skilled in the 71st. Duane Francies, often known as “Doc,” had been with the 71st from the beginning of the European war. He had taken some pre-med college courses and was frequently asked to provide first aid for minor injuries.

He flew an L-4H called ‘Miss Me!?’ He said: I named my plane ‘Miss Me!?’ Because I wanted the Germans to do that, the reason for the exclamation point, but I also wanted someone back home to ‘miss me’, so there was the question mark.”

On April 11, Francies and Lieutenant William Martin, his observer, were seen flying ahead of the 5th Armored about 100 miles to the west of Berlin. They saw a German motorcycle and sidecar speeding along a side road not far from the 5th’s approaching vehicles. They moved closer to get a better look and discovered a Fieseler Fi 156 Storch observation plane flying 700 feet over some trees.

Francies and Martin gave up on the motorcycle outfit after realizing they had to act quickly to stop the Storch from informing them of their 5th position.

Afterward, Francies wrote: “The Storch had an inverted eight Argus engine. It was also a fabric Job and faster and larger than ‘Miss Me!?’. It spotted us and we radioed: ‘We are about to give combat.’

‘But we had the advantage of altitude and dove blasting away with our Colt. 45s trying to force the German plane into the fire of waiting tanks of the 5th. Instead, the German began circling.”

Francies and Martin had opened their aircraft’s side doors and fired their pistols at the Storch while hovering just above and over the German aircraft. They observed damage to its right wing, fuel tank, and windscreen. Francies then reloaded while holding the Grasshopper’s control column between his knees. He wrote: “The two planes were so close I could see the Germans’ eyeballs, as big as eggs, as we peppered them.”

The Storch made a low turn that was too low in an attempt to dodge the American aircraft that followed it everywhere, and the tip of its right-wing hit the ground as a result. Before ultimately coming to rest right side up, it spins around and cartwheels while losing control of its right-wing and undercarriage.

Francies landed nearby, and he and Martin immediately went to the crash. The German crew had abandoned their machine stumbling and confused. The pilot hid behind a mound of sugar beet when they spotted the Americans coming, and the defeated observer fell to the ground.

Francies rushed over and went to aid the observer after noticing that they had been struck in the foot. When he removed the man’s boot, a.45 bullet was found inside. The pilot emerged with his hands raised after Martin, who had now also reloaded his gun, fired a warning shot.

A German flag they discovered inside the Storch was taken by Francies, along with the pilot’s uniform insignia. He wrote: “I never found out their names. They could have been important, for all I know. We turned them over to our tankers about 15 minutes later, after the injured man thanked me many times for bandaging his foot. I think they thought we would shoot them.”

Francies and Martin were scouting in advance of the 5th when some of the division’s components arrived at the Elbe not long after their aerial victory. A group of Soviet soldiers riding steppe horses approached them after they had flown across the river and landed on the other side. The soldiers were dressed in grey greatcoats.

The Russians moved back when they noticed the white star insignia on the Grasshopper, but they were unfriendly, and later the Americans boarded their aircraft and went back to the 71st. They had not realized that they were supposed to remain on the ‘American’ side of the Elbe.

Francies had twice been recommended for the Distinguished Flying Cross but had not been awarded it by the conclusion of the war. The recommendations were forgotten as the years went by. Francies was a Korean War veteran before beginning his career as a commercial pilot. In his book The Last Battle from 1966, historian Cornelius Ryan writes about his exploits. Harry Jackson, a US senator, pushed for the recognition of Francies’ accomplishments, and the following year, Francies finally received his DFC.

Spitfires Over Berlin is published by Mortons Books and is available to order here.

Photo by ERIC SALARD from PARIS, FRANCE, and Marie-Lan Nguyen via Wikipedia and Mark Felton Productions via YouTube